Chicago theater lore sometimes still seems stuck in Steppenwolf in the 70s, despite the emergence of so many notable ensembles since the days when Gary Sinise, Terry Kinney, and Jeff Perry began putting on shows in the basement of a Highland Park church. In some ways, it’s understandable—Steppenwolf provided an enduring blueprint for ensemble-based companies that emphasized grit and guts over glitz, even as their first members departed for careers in Hollywood and big Broadway productions. (Steppenwolf’s production of Samuel D. Hunter’s Little Bear Ridge Road, starring Laurie Metcalf, opens on Broadway next month.)

No Stars in Jefferson Park by Maggie Andersen

Northwestern University Press, paperback, 268 pp., $24, nupress.northwestern.edu/9780810149519/no-stars-in-jefferson-park/

No Stars in Jefferson Park: An Evening of Storytelling and Celebration

Tue 10/28 8 PM, Steppenwolf 1700 Theater, 1700 N. Halsted, steppenwolf.org/lookout, $23

So for that reason alone, Maggie Andersen’s memoir, No Stars in Jefferson Park, is a valuable document of the time after Steppenwolf, particularly in the period from the early 90s to the early aughts, when a new wave of ensemble-based companies stepped into the spotlight, including Lookingglass, A Red Orchid Theatre, and the now defunct companies House Theatre of Chicago and Defiant Theatre.

A founding ensemble member of the Gift Theatre, Andersen was essentially present at the company’s birth. The Gift was conceived by Michael Patrick Thornton and William Nedved in 1997 while they were students at the University of Iowa, and the name comes from a line in Jerzy Grotowski’s Towards a Poor Theatre: “The actor makes a total gift of himself.” But their first production (Howard Korder’s Boys’ Life, directed by the legendary Sheldon Patinkin) wasn’t until December 2001. Andersen was in that show and other early Gift productions. She was also Thornton’s girlfriend—they met first as theater kids in high school and became romantically involved after graduation.

Thornton and Andersen had more than a love of theater in common. Andersen grew up in Ravenswood with two sisters, in a family flat with a grandmother and mother who always budgeted for theater outings, eventually taking Andersen with them. Thornton, an only child, grew up in Jefferson Park, which never had a resident theater company until the Gift put down roots there. “He and I shared a dual citizenship to the world belonging to Chicago artists and the world belonging to its working classes,” Andersen writes. “Some choose one identity over the other, but we were proud to claim both, and I couldn’t really connect with someone who didn’t understand that. But I had mistakes to make.”

The company (and Thornton in particular) was soon on an upward trajectory, winning rave reviews. Thornton was also appearing onstage with larger theaters around town. And then in March 2003, just after turning 24 and while celebrating Saint Patrick’s Day with Andersen and other friends, Thornton had a series of spinal strokes that put him in the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (now the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab). Andersen went from artistic muse/collaborator to caregiver as Thornton spent months trying to regain some mobility and figure out how to still be an artist without the full use of his physical instrument.

Andersen was there for part of Thornton’s journey. But her memoir is really about trying to find her own voice and identity apart from the supportive-partner role for which she never auditioned, and which she eventually abandoned, along with acting (she remains a member of the Gift ensemble, however). She left Thornton and Chicago twice after his health crisis: once to attend a writing workshop in Prague in 2004, where she had an affair with a fellow student, and then for an MFA program at Western Michigan University, where she studied with fellow working-class Chicagoan Stuart Dybek. She now teaches English at River Forest’s Dominican University.

The story in No Stars moves back and forth in time, starting with Andersen, Thornton, and a couple of friends going to a bar, where Thornton (who uses a wheelchair) is mistaken for a wounded vet and thanked for his service. The actor and director’s dark Irish humor comes through clearly in Andersen’s telling throughout the book, as does their mutual growing anguish as they realize that they’re not going to make it as a couple.

Andersen’s memoir is also valuable as a chronicle of caregiver guilt and exhaustion. The bulk of the story takes place in 2003 and 2004 and deals with the days immediately after Thornton’s stroke when his survival wasn’t assured (in one searing moment, Andersen recounts a phone call with Patinkin, telling him that Thornton has received last rites), and the year or so following. After his release from rehab, Thornton and Andersen moved from their apartment into his parents’ house. Andersen uses the format of dramatic dialogue to recount the night of their final breakup in his parents’ backyard, including the offstage voices of Thornton’s mom, Rita, and a neighbor loudly worrying about what they’d do if one of their kids got sick. “I pray, I go to church, I’m a good person, but so is Rita.”

Catholic guilt is a component of the story that Andersen is telling, along with the “stand by your man” assumptions that others made about what her role in Thornton’s life would be going forward. “We broke up, in part, because I needed to tell the truth now to survive, and Mike still needed imagination,” Andersen writes. She tells that truth with gimlet-eyed clarity, compassion, and love for her family, Thornton and his family, and their creative families of affinity.

If you’ve been following Chicago theater for a while, there’s plenty of inside-baseball stories here about Gift artists and others. (Poignantly, three of the people who played major roles in the Gift and who appear in these pages—Patinkin, Mary Ann Thebus, and John Kelly Connolly, who drove Andersen and Thornton to the hospital on the night of Thornton’s stroke—are now dead.) But Andersen hasn’t written a salacious tell-all, and she’s certainly not asking for anyone’s sympathy. The last chapter, set in 2022 at a 20th-anniversary celebration for the Gift, ends with Andersen remembering Thornton reading James Joyce’s Ulysses to her, and thinking of Molly Bloom, “who had gotten the final word in the book.” Joyce, observes Andersen, once said that “‘yes’ was a feminine word, the acquiescing word, the end of resistance, and maybe that’s why I had stopped saying it.”

By saying “no” to one narrow path that was thrust upon her and Thornton, Andersen’s memoir shows that there are other roads waiting and other ways ahead. She and Thornton have both found new partners; they are still friends, and the actor has found even more success after his stroke than he had before (he currently stars on Broadway as Lucky in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot alongside Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter). No Stars in Jefferson Park is an important snapshot of a particular era in Chicago theater. It’s more important as a warm and unwavering portrait of overcoming the guilt of claiming your life as your gift.

Reader Recommends: ARTS & CULTURE

What’s now and what’s next in visual arts, architecture, literature, and more.

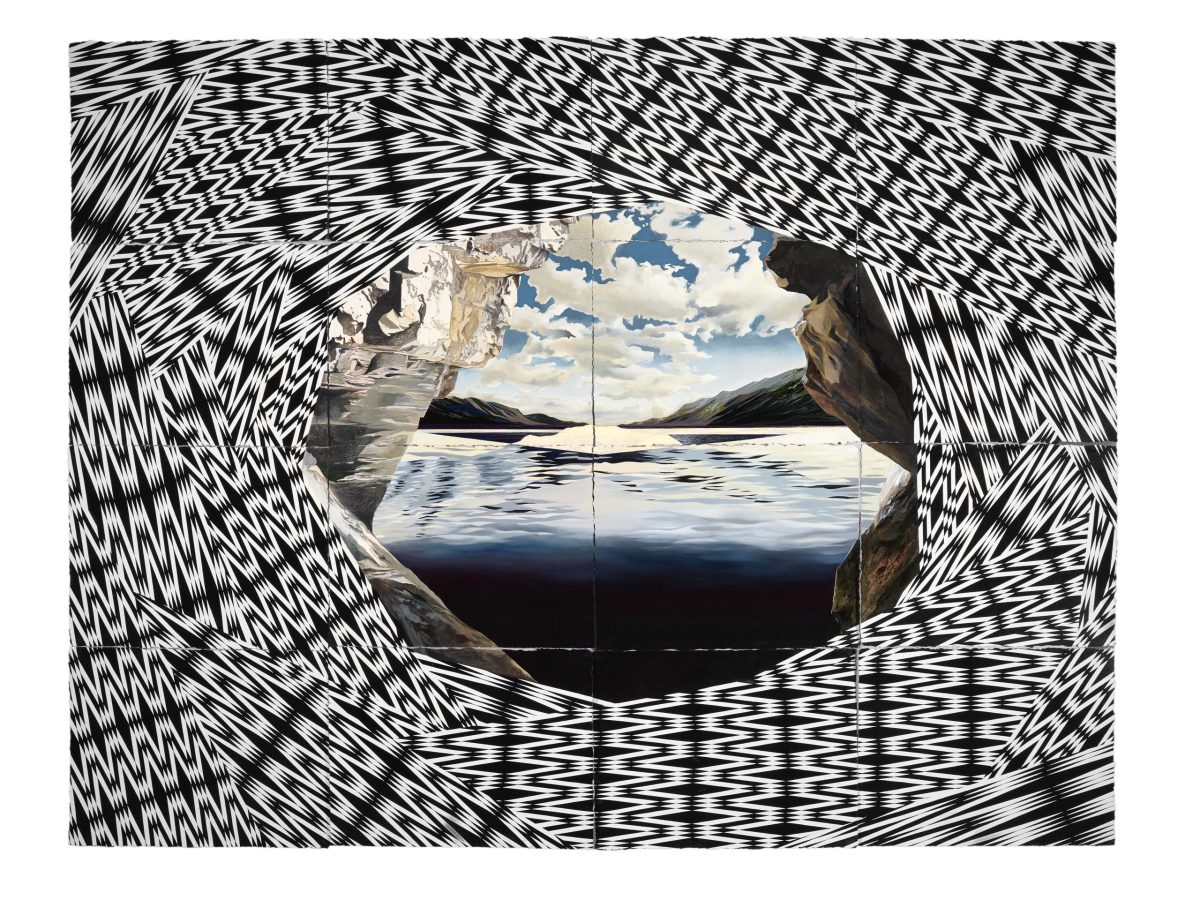

Andrea Carlson: A Constant Sky compiles 20 years of the artist’s paintings.

September 24, 2025

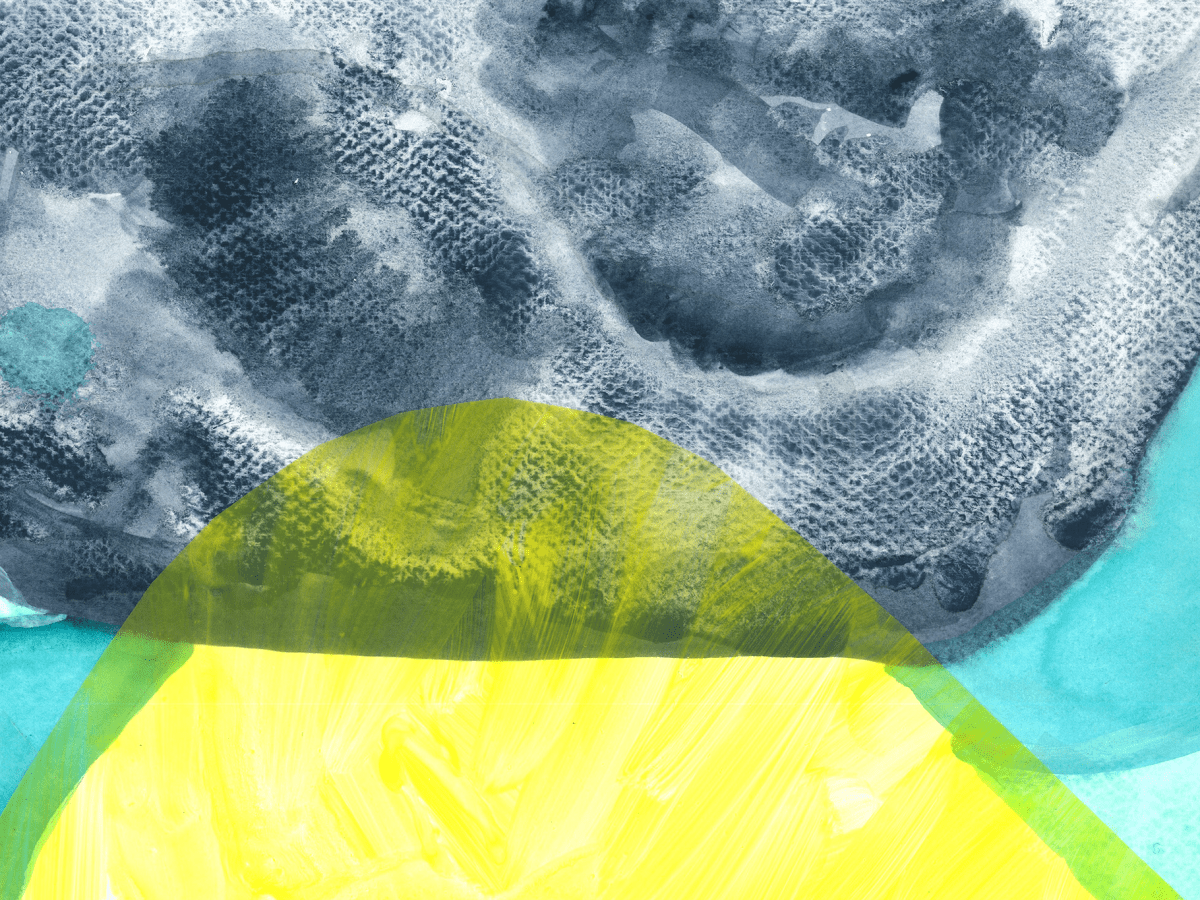

In “Flaming Memory,” the artist embraces paint as a volatile, volcanic material.

September 22, 2025

Bethany Collins’s “Dusk” is a provocative exhibition rendered in graphite gray.

September 18, 2025September 18, 2025

“Sacred Containers” at Chicago Artists Coalition showcases vessels of culture, history, and identity.

September 15, 2025September 15, 2025

There’s no unifying mood to be found in “Pure Moods,” but maybe that’s the point.

September 15, 2025September 15, 2025

Victoria Martinez matches the passion and complexity of Magda Portal at the Poetry Foundation.

September 12, 2025September 12, 2025