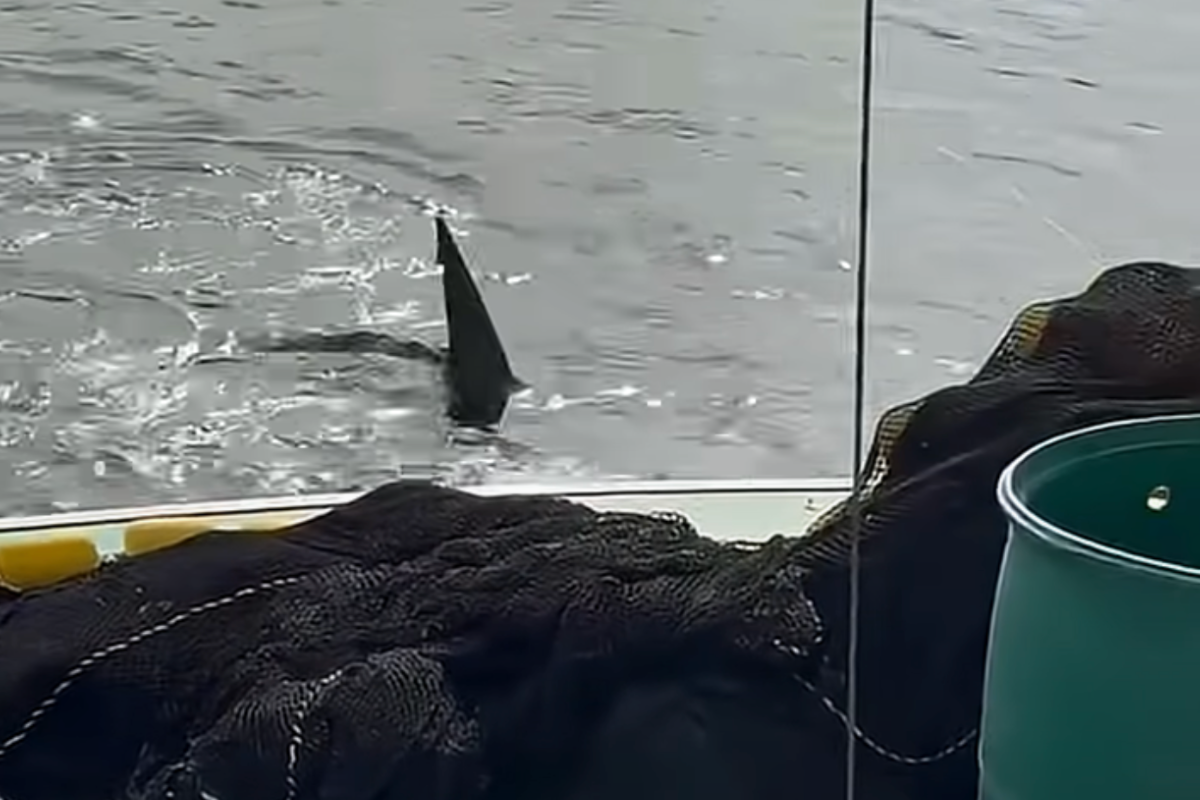

Ashley McLennan and her husband, Shaun, of South Thomaston were fishing off Boothbay this week when their sternman, Ryan Feener, saw a dorsal fin poke above the water that he at first assumed was a porpoise.

It was not a porpoise.

It was something far more dramatic: A great white shark devouring a seal, within feet of their boat. The shark lingered for several moments near the boat, seemingly unbothered by the human presence. At one point, a chunk of seal floated to the surface. The shark’s loitering allowing the crew to capture stunning video of the Wednesday, June 25, encounter which they shared with the Midcoast Villager.

“We were pretty surprised,” said McLennan. “It was terrifying and thrilling.”

Fortunately, they were already in a bigger boat. All three of the crew were in their main boat, leaving no one in the dinghy that towed the other end of their seine.

McLennan, it turns out, is something of a sharkophile and even has an app on her phone that tracks tagged sharks. She’s seen occasional shark pings in the waters off Midcoast Maine over the years, including one shark named Penny that she tracked for a while, but she never expected to see one so close.

“That was the first time we have ever seen one. It’s something I always hoped we would get to encounter, but never thought it would actually happen,” she said.

Two New England scientists who are authorities on white sharks — Matt Davis with the Maine Department of Marine Resources and Greg Skomal with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries — confirmed to the Villager that the animal in the video is indeed a great white shark.

Walter Golet, a professor at the University of Maine’s School of Marine Sciences, who has participated in shark research with both, brought the video to their attention after he was contacted by the Villager.

The fact that the shark swims right up to McLennans’ boat shows how “curious” white sharks can be, said Davis, who has tagged white sharks and studies highly migratory species for the state. The shark’s sex can’t be determined from the video, but its size indicates it’s probably a juvenile, he said.

White sharks have not been studied in depth in Maine since they have historically been more common in the waters off Southern New England, especially around Cape Cod. That could be changing, however, as Maine’s booming seal population may be drawing more sharks further north.

“We know white sharks which move through and use Cape Cod waters are also using Maine coastal habitat to some extent, with a substantial number of white sharks which were tagged there (thanks to Greg and his collaborators) detected on Maine DMR receivers,” Davis said.

Maine’s first-ever fatal shark attack on record occurred in 2020, when a 63-year-old woman was attacked while swimming with her daughter off Mackerel Cove on Bailey Island in Harpswell. A tooth recovered from the victim confirmed it belonged to a great white. The unprecedented attack prompted the state to step up its research efforts into white sharks, whose behavior in the Maine had previously been poorly understood.

Davis and his colleagues just published early findings from that effort in a peer-reviewed academic journal in March.

“While significant progress has been made to characterize life history patterns, movement ecology, and regional estimates of abundance of white sharks,” they wrote in the introduction to their paper, “patterns of spatial distribution remain relatively unknown in the northern Gulf of Maine.”

The study tried to change that, using acoustic sensors that could detect sharks previously tagged off Cape Cod and Hilton Head, South Carolina. It tracked 107 tagged white sharks, with their numbers peaking between July and September, including multiple detected in “close proximity to several of Maine’s western beaches” and islands.

Still, the researchers caution, they’re playing catch up, and their data is incomplete. Notably for Midcoast and Down East residents, their sensors were mostly concentrated in the western Gulf of Maine, off Southern Maine, so “future research should include expanded receiver coverage in eastern Maine and the use of additional tagging technologies.”

Seals populations, after being devastated in Maine and other parts of New England, have been booming since coming under federal protection in the 1970s. And sharks, which are also now federally protected, follow their prey. Younger sharks prey mainly on fish, squid and smaller sharks, but they transition to larger prey, like seals, as they reach maturity.

Globally, white sharks are deemed “vulnerable to extinction risk,” but in the western North Atlantic, which includes Maine, research suggests “a slow state of recovery,” according to Maine DMR.

Still, experts say swimmers and paddlers in Maine should not be overly concerned.

“Unwanted shark encounters are exceptionally rare for your average ocean recreator,” said Davis, before advising general safety protocols: Stay close to shore, swim and paddle in groups and avoid swimming near seals or schooling fish.

The Florida Museum of Natural History, which administers a major database of shark bites, notes that wasps, snakes, bees and lightning strikes, not to mention car crashes and drowning, are responsible for far more fatalities every year than sharks. There was only one fatal shark attack in the U.S. in 2024 and some years see zero.

Notably, perhaps, June 20 was the 50th anniversary of the release of “Jaws.”

This story appears through a media partnership with Midcoast Villager.