By Rachel Crumpler and Taylor Knopf

In early September, video of a man stabbing 23-year-old Ukrainian refugee Iryna Zarutska to death on a light rail car in Charlotte shocked the country. People from across the political spectrum demanded answers: How does a horrific, unprovoked attack occur between two strangers? What needs to change so something like it doesn’t happen again?

Law enforcement officers say the man was Decarlos Brown Jr., whose criminal and mental health record quickly came under scrutiny. The incident also fueled new legislation by North Carolina’s Republican leaders, intended to be tougher on crime.

But the new bill — passed easily in both the state Senate and House of Representatives — doesn’t add funding for North Carolina’s mental health system.

Brown, 34, was diagnosed with schizophrenia and living on the streets. Over the past two decades, he’s been arrested more than a dozen times, including several low-level misdemeanors. In 2015, Brown was convicted of armed robbery and served more than five years in prison. During his last encounter with law enforcement in January, when he repeatedly called 911, he reportedly told officers that “man-made” material was inside his body, controlling his actions.

Brown’s mother says she tried to find him psychiatric help. His sister says if he’d received proper treatment, the killing could have been avoided. Many say Brown should have been locked up — either in a jail or psychiatric facility. The reality is he spent time in both, and he didn’t get the help he needed.

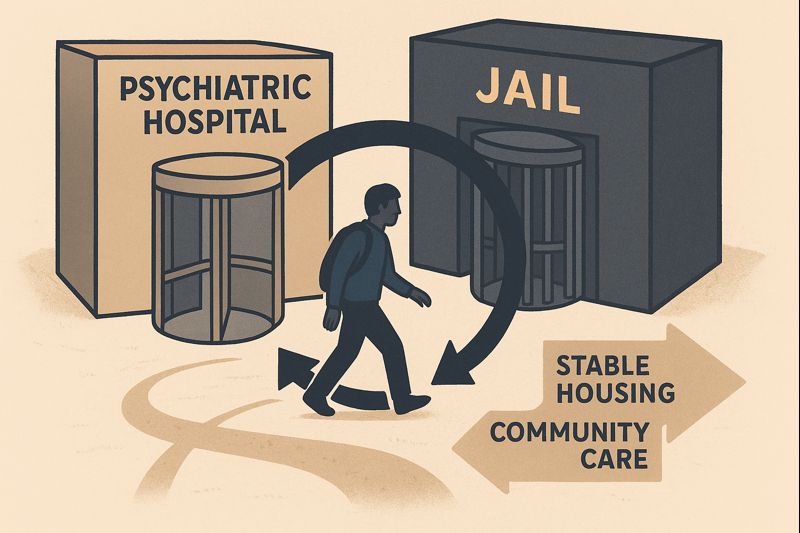

People with severe mental health disorders often cycle in and out of hospital rooms and jail cells, with little to no mental health treatment in between. Many also struggle with basic needs — housing, employment, access to care — that, if met, would help them be productive and stable in the community.

Mental health experts say they have long been familiar with the fractures and holes in the criminal justice and mental health systems that were exposed by the Charlotte killing. But the general public doesn’t see them until such a tragedy throws the gaps into the spotlight.

“I believe this incident really highlights a systemic failure, not an individual or family failure,” said Kate Weaver, executive director of NAMI Charlotte, an organization that supports people with mental illness and their family members. “When people with serious mental illness don’t receive consistent care, there are risks.”

If North Carolina is serious about finding solutions, advocates say, it will take resources and willpower to overhaul parts of the mental health system that aren’t working and to establish an array of services in the community that actually support people.

Those resources have not been forthcoming.

Falling into chasms

People often first encounter the mental health system during a crisis — either through an arrest or an emergency room visit. In both scenarios, law enforcement officers are typically involved.

Across the U.S., jails have become de facto mental health facilities. The federal Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration estimates that 44 percent of people in jails and 37 percent of those in prisons have a mental illness. Jails, in particular, are often ill-equipped to manage people with complex health needs; the costs for managing those mental health issues can be too much for smaller county budgets.

When someone is brought to an emergency room in a mental health crisis — whether it’s a suicide attempt or a psychotic episode — they are often placed under an involuntary commitment and undergo forced psychiatric hospitalization. By state law, police officers serve involuntary commitment court orders and often transport patients between hospitals, frequently in handcuffs and shackles.

The experience can be jarring, and scarring.

“Transitions in general for all human beings are tough,” said Cherene Caraco, director of Promise Resource Network, a mental health agency based in Charlotte that is staffed entirely by people who’ve had mental health struggles. “And then you’re talking about a transition into an institutional setting and then out of an institutional setting where you are forever changed when your rights are removed.”

A patient room in the new 16-bed facility-based crisis center in Burlington, a short-term inpatient option for those who need up to a week of psychiatric care. Credit: Taylor Knopf

A patient room in the new 16-bed facility-based crisis center in Burlington, a short-term inpatient option for those who need up to a week of psychiatric care. Credit: Taylor Knopf

Caraco said most people exit psychiatric hospitals, jails and prisons without follow-up support. “You come out to nothing,” she said.

Ted Zarzar, a psychiatrist who divides his time between UNC Health and Central Prison in Raleigh, said the period where people reenter their communities is high-risk for folks with a mental illness. Their symptoms can spiral downward without continued care.

Many times these people are released from carceral settings without a job or a place to live. Some people may have a single outpatient mental health appointment scheduled and a 30-day supply of their medications.

Others might just get handed a list of resources and phone numbers.

“I think it is the exception, rather than the rule, that somebody goes to a follow-up appointment,” Zarzar said. “At best, they end up in an emergency room or inpatient hospital and get connected that way. But at worst, they end up either back in jail or prison, or something horrific happens, like what happened in Charlotte.”

Without a direct handoff to true support and services, it is nearly impossible to stay stable in the community, Zarzar said. People often land right back in a hospital or prison cell in a frustrating — and costly — cycle of recidivism for which taxpayers pick up the tab. Incarceration in a North Carolina prison runs more than $54,000 a year. The average cost of a hospital stay in North Carolina is $2,881 per day, according to 2023 data collected by KFF, a nonpartisan health policy and research organization.

“We don’t have cracks in the system, we have chasms,” Caraco said. “And once you fall into that chasm, it’s not easy to come out of that without a lot of support.”

‘Not a casserole illness’

Lately, lawmakers from New York to California have proposed to involuntarily hospitalize people who are homeless, to force them into mental health treatment. The bill passed by North Carolina lawmakers this week also seeks to push more people into involuntary commitments.

But many in the mental health and substance use treatment community argue that forced psychiatric hospitalization does not address severe and complex mental illness, and it doesn’t often yield positive results. These commitments are temporary, and people are often discharged without the community support they need. Coerced treatment can also lead patients to distrust the system and leave them reluctant to seek help the next time.

Bob Ward is a retired attorney who spent a decade representing people in involuntary commitment hearings in Mecklenburg County. Ward said he saw firsthand the lack of treatment and timely care. He said civil commitments of any kind — adult, minor, inpatient or outpatient — are “useless” if the right treatment and supportive services are lacking once the person comes home.

The continuous rise in involuntary commitments — which are intended to be a last resort for someone who is a danger to themselves or others — is a “sure sign of a failed system,” Ward said. A NC Health News investigation found that the number of involuntary commitment petitions filed in county clerk of court offices rose at least 97 percent between 2011 to 2021.

Only a fraction of those people end up making it through the whole commitment process to a psychiatric inpatient bed, according to a May report by Disability Rights NC. Many who work with people experiencing the process say it’s riddled with problems and needs significant reform.

Weaver, the NAMI Charlotte leader, said when it comes to involuntary commitment, it’s “difficult to balance people’s rights with public safety, and it is not against the law to have a mental illness.”

Friends and family also treat mental illness differently than they do other medical issues, Weaver said.

“If you had a loved one with a cancer diagnosis, your friends would rally around you, the casseroles would come, the lawn would get cut and you would have continuing care with a team,” she explained. “When someone in the family has a mental illness, it is not a casserole illness. People don’t come rally around that family, and there is no continuum of care.

“There is no mental health team that follows that person from the beginning, from illness to wellness.”

Weaver said families struggle to find lasting help for their loved ones — a situation that played out in the case of Decarlos Brown, the man accused in the Charlotte stabbing.

Brown’s mother said his mental health had declined significantly after his five-year prison stay. By this summer, he only had bits and pieces of mental health support, and he was homeless.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle agree that the system failed Brown.

“He was failed because his mother wanted somebody to pick him up, and there was not the willingness on the part of the system to do that,” Republican Senate leader Phil Berger told reporters on Sept. 22. “[Iryna Zarutska] was failed because there was a system that would allow someone like that to exhibit the sorts of problematic behaviors without there being any intervention.”

Berger questioned whether inadequate funding for mental health resources was at fault, instead suggesting that people were unwilling to step in with already available resources.

Solutions include support, more options

In response to the killing, mental health experts who spoke to NC Health News highlighted the need for transitional support for people leaving jails, prisons and psychiatric facilities. They also emphasized the need for money for an array of community mental health services that could prevent stays in jails and psychiatric facilities, which are expensive and often the least effective option.

The mental health system is designed to take a faulty approach with limited options, said Caraco, director of Charlotte’s Promise Resource Network.

“You do this, and then you do this, and then you do this. You need a referral. You need an assessment. It is time-limited. You need a diagnosis. You have to comply with medications,” she said. “All of the things that lead people to not being able to engage in anything that feels meaningful.”

There’s a predetermined set of services and options. Either it works for people, or they walk away, she said.

Caraco said her organization ends up serving many of those who’ve walked away from traditional mental health care that they found ineffective or harmful.

“Our system should be set up like a buffet. There are times where you want nothing but crab legs, and there are times you’re going to eat dessert first, but you have an array of options available in front of you to choose from. Because at different times, different things feel right,” she said. “That array has got to be accessible to you.”

Caraco believes that connecting people with certified peer support specialists at hospitals or jails would help bridge some of the gaps. Peers draw on their own experiences with mental illness, substance use, homelessness and/or incarceration, making them more relatable to people navigating the same challenges.

Hospital emergency departments already employ people who are often referred to as “sitters,” whose role is to sit with patients at risk for suicide to make sure they are safe. Caraco suggested that hospitals replace sitters with community-based peer support specialists.

“They’re sitting in the emergency department. They’re interacting, they’re developing plans, they’re getting deeper into the relationship and what’s going on,” Caraco said. “And trying to establish that rapport and that relationship right off the bat.”

If these people were peer support specialists from a community-based organization, instead of hospital employees, that relationship could continue after the patient is discharged. Some psychiatric hospitals use “peer bridgers” who build relationships with people while they’re still inpatients, with the goal of staying connected once the patient is released and navigating the community mental health system.

Founder and CEO of Promise Resource Network Cherene Caraco is flanked by peer support specialists and local law enforcement officials, including Mecklenburg Sheriff Gary McFadden, at the 2022 ribbon-cutting ceremony for the mental health agency’s peer-run respite in Charlotte. Credit: Taylor Knopf

Founder and CEO of Promise Resource Network Cherene Caraco is flanked by peer support specialists and local law enforcement officials, including Mecklenburg Sheriff Gary McFadden, at the 2022 ribbon-cutting ceremony for the mental health agency’s peer-run respite in Charlotte. Credit: Taylor Knopf

That same concept can also be applied to jails and prisons, Caraco said.

Peer support specialists and social workers are being incorporated into mental health crisis responses more often. Initiatives like the HEART team in Durham use a mental health crisis response unit to respond to 911 calls related to mental illness, homelessness and substance use. These specialized teams can help steer people to community support instead of emergency rooms or jails.

“We need folks who have lived experience — not only of mental health disabilities, but of criminal justice involvement and incarceration, because no one wants to talk to people who can’t relate to them,” said Corye Dunn, policy director with Disability Rights NC.

Bring care to where people are

Dunn said there’s also an opportunity to bolster Assertive Community Treatment teams, which are designed to be community-based, wrap-around services for people with severe mental illnesses. She suggested there should be more forensic ACT teams that include peer support specialists who were previously incarcerated.

Zarzar said ACT teams break down barriers to accessing care by bringing it to people where they are — even if it’s under a bridge.

“It takes the inpatient treatment team and puts it on the outside,” he said. Teams include psychiatrists, nurses, peer support specialists and more. They have frequent contacts with clients to help get their basic needs met and reach their personal goals.

Zarzar said he’s seen positive outcomes, but it hinges on a person’s voluntary participation.

Clinical social worker and longtime mental health advocate Bebe Smith said it can be difficult for people to qualify for ACT team services, as they have to fit narrow criteria of a diagnosis of severe and persistent mental illness plus a high utilization of services.

They must also have Medicaid and be enrolled in one of North Carolina’s “tailored” plans.

According to the N.C. Department of Human Services, North Carolina operates 87 ACT teams — a number that has remained relatively stable over the past decade. Between 6,400 and 6,800 individuals received ACT services at any given time last year. In fiscal year 2024, the state spent $8 million in non-Medicaid funds to cover treatment for uninsured individuals, supporting 915 people.

Seven ACT teams serve Mecklenburg County, six of which are open to new referrals with no waitlist, according to DHHS. The Assembly reported that Brown was working with an ACT team for at least some of last year, though it’s unclear if he still was getting services at the time of the light rail murder.

In fiscal year 2025, ACT participants statewide saw a 19 percent decrease in emergency department use and a 2 percent reduction in homelessness, according to data DHHS provided to NC Health News.

However, Smith said that the quality of services can vary across ACT teams. While it’s supposed to be intensive, wrap-around care, sometimes all that is provided to the patient is “a brief touch or medication delivery,” she said.

Opportunities during reentry

Many people with complex mental health needs end up in the most expensive settings — hospitals, jails, prisons.

System experts see an opportunity to interrupt how people cycle through them by investing more in reentry supports that will allow people to land — and stay — on their feet in the community.

Zarzar, the psychiatrist treating people in the community and in prison, said he often sees people bounce between those settings.

It’s estimated that that 44 percent of people in jails and 37 percent of those in prisons have a mental illness, but when they are ultimately released many don’t receive the care they need. Credit: Rose Hoban / NC Health News

It’s estimated that that 44 percent of people in jails and 37 percent of those in prisons have a mental illness, but when they are ultimately released many don’t receive the care they need. Credit: Rose Hoban / NC Health News

That’s driven his work as the director of FIT Wellness, a program for people with a serious mental illness leaving the state prison system or jails. FIT Wellness provides psychiatric and physical health care — along with connections to community support like housing and transportation — to people in Wake, Durham, Orange and New Hanover counties.

The program employs formerly incarcerated people trained as community health workers to work with people being released from incarceration. A team member will meet with a person before they are released to discuss their needs and establish a pathway to care.

“Thus far, we’re having a lot better success at getting people to come in to that first appointment,” Zarzar said. “It still can fall apart after that, but during this high-risk, high-needs period — that first month or so after people get out — we’re doing a better job in terms of getting people to come.”

Along with addressing mental health needs, advocates say investment in meeting people’s basic needs — housing, food, work or school — could help reduce recidivism. Data shows that about two-thirds of unhoused people also have mental health disorders.

“We are responsive after the fact, and so we’re often willing to invest in things like harsher prison terms. But again, that’s not going to prevent the new person from engaging in some act,” Apryl Alexander, director of UNC Charlotte’s Violence Prevention Center, said. “I’m waiting for the time that we get invested in putting our money into prevention.

“If we take care of basic needs, we see all of this [criminal involvement] reduced.”

The barriers to housing are many, but groups like Queen City Harm Reduction in Charlotte are piloting Housing First programs with success. These programs help people navigate the barriers to housing — like evictions or criminal records — that many people living on the streets face. The program uses case managers to help find flexible landlords, track down necessary documentation and secure a rent deposit. The program doesn’t require someone to be abstinent from substances to qualify for housing. Program director Lauren Kestner has found that many people who find employment and get housed wind up reducing their drug use.

Mecklenburg County Sheriff Garry McFadden said it costs $198 a day to house someone in Mecklenburg’s detention center. He contended that those funds might be better spent on early intervention mental health treatment and reentry support to help reduce people’s recidivism.

Harold Cogdell Jr., a Charlotte defense attorney and former assistant district attorney at the Mecklenburg County District Attorney’s Office, said better supporting people before a crime occurs is a better approach than “paying on the back end.”

“There is a victim, so the harm has been done,” Cogdell said. “If we focus more on making a person holistically healthy on the front end, that increases the likelihood that … the crime may never be committed.”

‘We have to do more’

“The state has an obligation to build systems that make sense, and this does not make sense,” said Disability Rights’ Dunn. “[The system is] very convoluted. It is a one-size-fits-all approach that is going to increase demand without improving outcomes, on the mental health side at least.”

For decades, the state shuttered state psychiatric hospitals with promises to spend the savings on community resources that never materialized. Many say this contributed to the dearth of services seen today.

A decade after the closure of the state’s largest psychiatric facility, Raleigh’s Dorothea Dix Hospital, an infusion of $835 million into behavioral health came from Medicaid expansion sign-on bonus. That money has allowed the state to catch up some, raising rates for providers and investing in mental health crisis services, pre-arrest diversion programs and more.

State health officials have allocated $99 million to boost services specifically for people in the justice system.

The additional funding has allowed North Carolina to improve some metrics, such as increased state psychiatric bed availability, decreased emergency department use for mental health holds, and fewer people in jails and prisons with mental health diagnoses, according to DHHS.

But, in a statement to NC Health News, the state health department acknowledged there’s more to be done to support people with mental health and substance use issues as they leave jails and prisons.

“Upon their release from incarceration, we have to do more to protect both their success and public safety,” the department said in a statement to NC Health News.

The reality, though, is that the bill passed by state lawmakers this week in response to Zarutska’s death did not add any funding to bolster the mental health system.

That, along with uncertainty looming from cuts to Medicaid funding as part of President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill, could put much-desired changes increasingly out of reach.

“We can’t ignore the fact that we haven’t invested in mental health services,” Weaver, the NAMI Charlotte leader, said. “As a country, we’ve taken away more and more mental health support, and with the looming Medicaid cuts coming, as an organization, we’re bracing ourselves for a lot more people being uninsured, unable to access resources and struggling even more.”

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.