Josh Smith, Broken Country, 2025, © Josh Smith, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Josh Smith, Broken Country, 2025, © Josh Smith, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

By JANE HOROWITZ, September 26, 2025

Walking into David Zwirner’s Los Angeles gallery to view Josh Smith’s Destiny – made up of 21 works featuring the iconic image of the Grim Reaper – I was a bit anxious, prepared to be surrounded by bleakness, chaos, and all matters of darkness. After all, this is an exhibit featuring paintings of a demon racing around New York City by bike in the dead of night, often accompanied by a scythe, seemingly ready to strike down anyone who crosses his path.

A black cat lurks, fires blaze. The paintings’ backdrops are places of transportation—bridges, subways, gas stations. The bikes aren’t bright and shiny but well-worn and twisted. Here comes our destiny, alright: the apocalypse.

But Smith’s work took me somewhere else entirely. The bold colors, frenetic motion, and the Reaper’s alternately grinning and nefarious expressions elicited something more akin to excitement — a rush at seeing how this archetypal figure has taken on new life as a roving bon vivant. The Grim Reaper, sometimes depicted faceless, wears his expressions happily. And the paintings are big, many 7 x 7 feet, thick with paint and expressive strokes. You can see Smith’s craft with every drip of paint.

Smith goads us— is this black comedy or tragedy? Is he the Grim Reaper… or are we?

What becomes clear when speaking with the artist is that “everything I do is about me,” Smith said while touring his work at the gallery. “But I mean it to be everybody. I chose this character ’cause it could be any of us. We’ve all seen the movies, where the world’s essentially over, but there are a few souls that are still out there. I’d like to think with all the bad stuff, there’s a whole class of people, always moving, that are on to their own thing.”

While the show seems ready-made for these chaotic times, Smith views the reemergence of his alter ego as a neutral cipher. He first introduced the character in 2017, his response to finding a religious flyer on a subway warning that death was imminent. Then, last year, a friend asked him to design a pizza box, and the robed skeleton was unleashed again.

He views the character as a beacon of hope, a comrade in arms — perhaps an unreliable narrator for these turbulent times. Like Smith himself, who claims to work constantly, the reaper represents movement. “They’re apocalyptic, but… people are surviving. I mean, it’s the death character, but I’ve come to think of it as a person… like family, friends.” He created the works in the spring of last year and concedes that times have “gotten darker,” the symbol taking on more gravity.

This approach to the reaper figure reflects Smith’s broader artistic practice, which has long been built on repetition and improvisation, whether depicting his own name, devils, palm trees… or reapers. The art world has taken notice over the past 20 years: he’s exhibited widely internationally, with solo shows at institutions including The Drawing Center in New York and Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Roma, plus group exhibitions at MoMA in New York and the Venice Biennale.

The Destiny paintings function almost as a series of vignettes, following the Reaper as it tears through the city past recognizable landmarks and barren streets. Smith’s Manhattan isn’t the gentrified metropolis that exists today but the rawer New York of the ’80s and early ’90s—perhaps reflecting the city that Smith, born in Japan and raised in Tennessee, moved to in the early ’90s.

The works are both expressionistic and cartoonish, occupying that liminal space between high art gesture and underground comic.

For all the calculated artistry, Smith’s inspiration for these urban environments comes from something much simpler. As deliberate as reintroducing the character may seem, Smith insists the environments he sets it in are inspired by simply walking outside. “I wouldn’t go out searching for something. I would just walk a couple of blocks and see something and be like ‘That’s good — just take a picture of it because I need it.'”

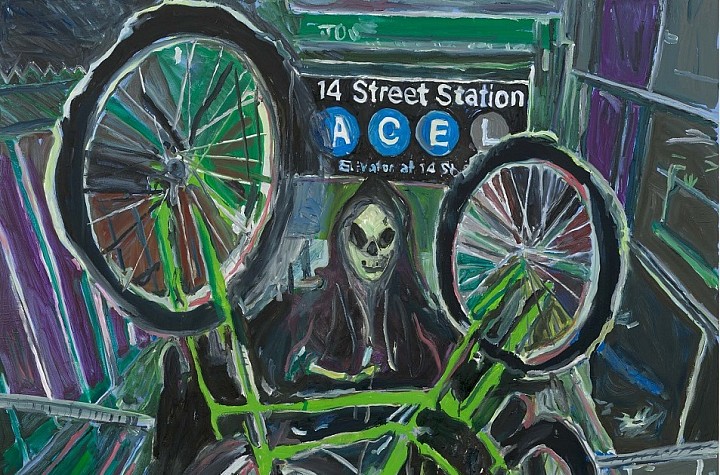

In Broken Country (2025), the Reaper holds his scythe like a flag, grinning as he bikes against the backdrop of the Statue of Liberty. In Me Again (2025), the reaper hoists his bike (with two extra tires) as he climbs the stairs of the 14th Street station, again with a grimace as if he’s continuing on his rounds for the night.

But The Getaway (2025) takes us elsewhere: the reaper’s robe has literally changed colors to hues of green, whirring happily down the street. In The Villager (2025), the character is surrounded by a downright vibrant cityscape as he crosses the Brooklyn Bridge, the skyline rendered in a palette of orange, green, blue, and purple. It’s also noticeably daylight, as if the character is coming back home after a night out (Smith lives in Brooklyn).

Josh Smith, Me Again, 2025, © Josh Smith, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Josh Smith, Me Again, 2025, © Josh Smith, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

The irony that New York serves as the backdrop for Smith’s first Los Angeles solo show isn’t lost on him. He conceded that if he were working in L.A. when he made this work, other influences might have creeped in. “I would love to have been here. This is equally as great as a landscape for these people… even driving from the airport, you can see it.”

This geographic displacement adds another layer to the work’s meaning—here’s an East Coast apocalypse being presented to a West Coast audience that knows something about end times, from wildfires to earthquakes to the perpetual sense that California exists on borrowed time.

Josh Smith, The Getaway, 2025, © Josh Smith, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Josh Smith, The Getaway, 2025, © Josh Smith, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

The artist’s exploration of these themes extends well beyond traditional painting. Smith has expanded his practice to include music, which he describes as the perfect outlet for the battles he has with his art. The music video Don’t, released in August, lays out his plea to keep out the intrusions of the world: “Please don’t fuck with me,” he pleads, identifying himself as an artist who makes paintings and needs to be alone. The video features the painting Incident at the Gas Station (2025), depicting two reapers—one splayed on the ground, clutching to his scythe, the other upright, holding his bike as he peers down on his doppelganger. Smith’s command to “don’t make something simple complicated” may sum up not only his approach to art, but the way to consume it.

Ultimately, Smith’s reapers don’t herald apocalypse so much as survival — the ability to keep moving, keep creating, keep finding beauty in urban decay. In an era when artistic practice itself can feel like an act of defiance, perhaps we’re all riding through the city at night, looking for the next gas station, the next bridge, the next place to catch our breath before dawn breaks and we have to do it all over again. The reaper grins because he knows the secret: the apocalypse isn’t coming — it’s already here, and we’re still pedaling.

Josh Smith: Destiny is on view at David Zwirner Los Angeles through November 1, 2025.