Texas Christian University’s mascot — the endangered, indigenous horned frog — is one aspect of campus tradition that Native American students easily identify with.

“A mascot does have meaning,” especially to indigenous students carrying the weight of their ancestors, says Annette Anderson, whose roots are Chickasaw and Cherokee. Her words are quoted in a book about TCU’s efforts to incorporate Native American perspectives into campus life and the university curriculum. “Imagine my relationship with the university if the mascot was the Apache, the Indians, or the Warriors.”

The horned toad is actually a lizard, an 8-inch-long reptile with bony spikes on its head. It is a survivor, the subject of colorful stories. It can shoot blood from its eyes. Its image is painted on ancient Southwestern pottery and chiseled into prehistoric petroglyphs that line Texas canyons.

When Anderson began working with TCU, the “sacred” school mascot opened a “psychological door,” she says in the book. A member of TCU’s Native American Advisory Circle, Anderson is among a dozen Indigenous scholars, students and alumni who candidly describe their positive and negative experiences at the university in the book, which was published last spring.

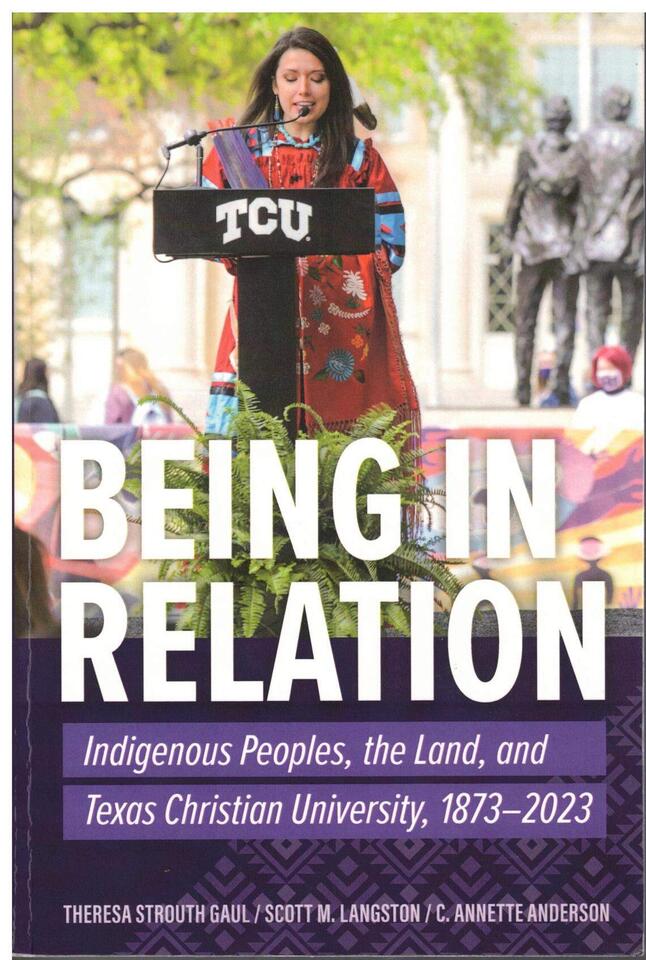

Titled “Being in Relation: Indigenous Peoples, the Land, and Texas Christian University, 1873-2023,“ the 242-page anthology chronicles a decadelong initiative to improve understanding of Native American perspectives at TCU.

The TCU Land Acknowledgement monument is a 3-foot-tall granite boulder conveying the message that the surrounding grounds were once Native land. Courtesy of Dr. Scott M. Langston

Anderson co-authored and edited the book with Dr. Scott Langston, TCU’s inaugural Liaison for Native American Nations and Communities, and with Dr. Theresa Strouth Gaul, who teaches Native literature at TCU.

The volume opens with a photo of TCU’s Land Acknowledgment monument, a rugged, granite boulder with a circular bronze plaque. Inscribed in two languages (English and Wichita), the plaque states “We respectfully acknowledge all Native American people who have lived on this land since time immemorial.” Fort Worth was the historical homeland of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, whose people lived, hunted, and migrated through lands today called North Texas. The monument, dedicated in 2018, is on campus between Reed Hall and Jarvis Hall.

Native students had initially hoped the Land Acknowledgment’s message would be incorporated into campus ceremonies as well as the academic curriculum. But in 2022, a TCU faculty senate committee tabled a motion related to the curriculum as “overly controlling,” according to Lauren Dunham, a Native-Alaskan descendant and political science major who graduated in 2023. “No Native American history class was taught during my four years at TCU. … We don’t have a tribal law class in the political science department. …There’s just not that university level engagement,” Dunham says in the book.

“TCU is still in its own little bubble,” asserts Tabitha Tan, a Navajo alumna and an environmental scientist. As an entering freshman in 1994, she recalled, “They didn’t know [if] I spoke English or still lived in tepees,” Tan says in the book.

“TCU has an image problem,” J. Albert Nungaray, a professional storyteller who graduated TCU in 2017 with a major in history and anthropology, says in the book. “It’s a school for rich, white kids with summer homes and daddy’s credit card.” His ancestors’ homes were among Pueblo communities in New Mexico.

A spokesperson for TCU did not respond to a request for comment for this column by presstime.

Dr. Wendi Sierra, an Oneida and an associate professor of Game Studies, writes in the book that the misconception she runs into is “that Native people are just mostly gone.”

Yet the book’s foreword maintains that an “Indigenous resurgence” is underway. The U.S. Census reports that more than 10 million Americans trace their ancestry to Native Tribes. About 75 percent live in urban areas, not on reservations.

“I remember learning in seventh grade in Texas history that some of the Native Nations of Texas were cannibals,” recalled Sierra, who succeeded Langston as TCU Liaison for Native American Nations and Communities. “That was in a textbook. … [W]hat I learned in my public education about American Indians was … extremely limited.” There’s a misperception that Indigenous people are “monoliths.”

Haylee Chiariello, a Cherokee, concurred. “[S]ome people come to TCU and don’t even understand that Native peoples had an ancestral language,” Chiariello says in the book. Each of the more than 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States have different tongues, governance, philosophies and ceremonies.

Efforts to improve Native American awareness at TCU

On the positive side, much has been accomplished since 2015 when TCU’s grassroots outreach initiative began. In 2016, the campus hosted a Native American and Indigenous People’s Day Symposium that has become a fixture. The Native and Indigenous Student Association (NISA), defunct since the late 1990s, has been rejuvenated. The organization provides a space where the sparse number of Indigenous students — perhaps several dozen, according to Langston — can meet with one another.

Chiariello, who drives a car with Cherokee Nation license plates issued in Oklahoma, says the questions her vehicle evoke turn into “an opportunity to share my story.” This year, she became the first TCU student to graduate with a Native American degree. She majored in journalism, dance and Native American expressions.

The Harrison, a campus administration building that opened in 2020, has two kaleidoscopic paintings by Comanche/Kiowa artist J. NiCole Hatfield (Nahmi-A-Piah). One painting, a commissioned portrait, is of Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, namesake of Quanah, Texas, a county seat. The second canvas, an older painting, depicts a Sioux woman known only as Mrs. Jack Treetop.

Sarah Tonemah, a Comanche/Kiowa native formerly with the TCU Theatre Department, applauds these selections, saying in the book that they remind students and outside visitors “that we are here.”

A number of Indigenous alumni quoted in the book say their next goal is to host a campus powwow, a colorful festival filled with Native drummers, traditional dancing, crafts, frybread, meat pies and Native games like stickball, which evolved into lacrosse. “People don’t realize that powwows are real,” Sierra says. Annually, North Texas powwows are held in Dallas; Arlington at the UTA campus; and Cleburne, which hosts a multi-day gathering. A local group is planning a Fort Worth powwow in 2026, according to Langston.

In the academic sector, Native students want to expand TCU’s curriculum to create more possibilities for a minor in Native Studies. No doubt, undergrads of many ethnicities would benefit from classes about Texas’ three federally recognized tribes (the Kickapoo, Tigua, and Alabama-Coushatta). Environmental science faculty, in concert with Native educators, could design an elective around the threatened status of the Texas horned lizard.

The popular reptile became TCU’s mascot in 1897 when yearbook editors photographed horny toads covering the football field. As soon as a cold wind blew in, the lizards burrowed underground to lay eggs. Loss of habitat and use of pesticides have shrunk the mascot’s numbers. Another culprit are fire ants, which attack native ant colonies, once the mainstay of horned frogs’ centuries-old diet.

TCU Magazine’s fall issue includes a lengthy article that explores the ten-year campus initiative. Headlined “A New Story on Ancient Land,” the feature recommends an array of books, music and podcasts that best “illuminate” Native history and culture. The new anthology “Being in Relation” ranks at the top of the list.

Hollace Ava Weiner, director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives, is an author and archivist who wrote fulltime for the Star-Telegram from 1986 to 1997.