We are deep into a completely new era of greenwashing, where some clever companies and countries have finally understood it makes more sense to erode our shared capacity to measure the hard reality of climate-change-causing gases, rather than to bother with easily debunked offsets.

Big tech is living this philosophy at every conceivable level, most obviously through the invention and widespread deployment of a machine that fabricates text, images and videos based off the mass-theft of most of humanity’s creative digital output.

We are rapidly losing friends and family to the “let me just ask ChatGPT” infoslop curse. Increasingly fascist-friendly tech companies are now free to spin hidden dials and shift global perceptions of an issue even worse than they could with social media algorithms. But that does not make the hard physics of greenhouse gas molecules, electrons and the roiling heat of the atmosphere any less real.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1222086

Meta stands out as a fantastic example of a corporation with rapidly rising climate and environmental impacts that aims to deal with them not through traditional greenwashing, but through a subtle and complicated sabotage of how impacts are measured and reported; far more nefarious than anything we’ve seen before.

Instead of a debate about rhetoric and claims (like Apple’s “carbon neutral” lawsuit), Meta has helped form a coalition of companies (known as the “Emissions First Partnership”) that directly lobbies for the adjustment of how its worst environmental impacts are measured, biased obviously towards minimising the numbers spat out the other end.

Independent. Irreverent. In your inbox

Get the headlines they don’t want you to read. Sign up to Crikey’s free newsletters for fearless reporting, sharp analysis, and a touch of chaos

By continuing, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

The context for this push is Meta’s frantic, anxious, infrastructure expansionism frenzy, and it’s worth understanding this before we dive into what it’s lobbying to change. Part one of this series will focus on the company’s current presentation, and part II will focus on its desires and dreams.

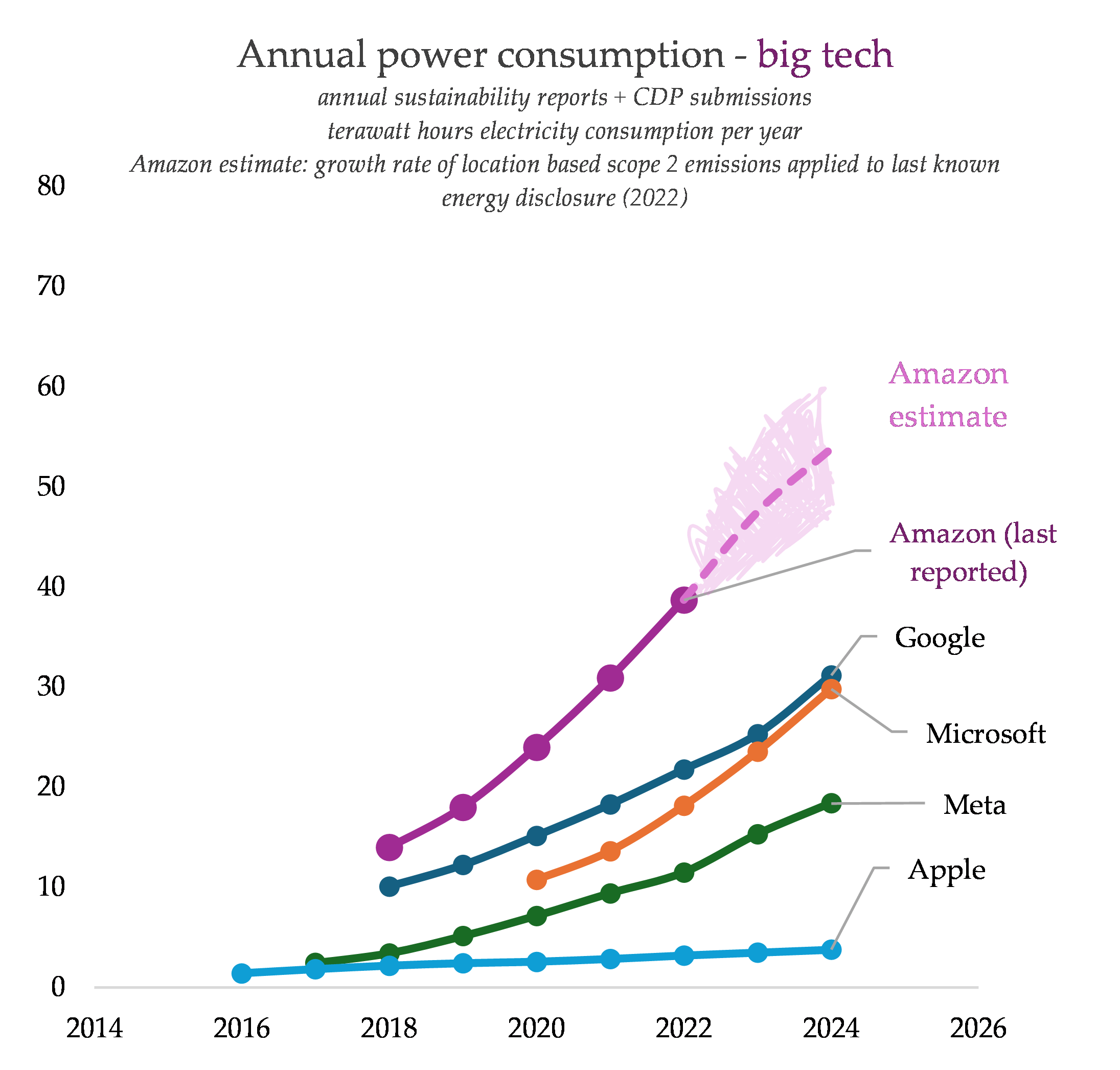

Meta’s latest sustainability report came out only last week, oddly released with zero orchestrated media coverage (I keep a running compilation of big tech climate and energy data here). Like Microsoft, Google and Amazon, Meta’s total electricity consumption has been on a massive tear for a half-decade, driven primarily by the expansion of data centres:

Source: manual compilation of company emissions data

Source: manual compilation of company emissions data

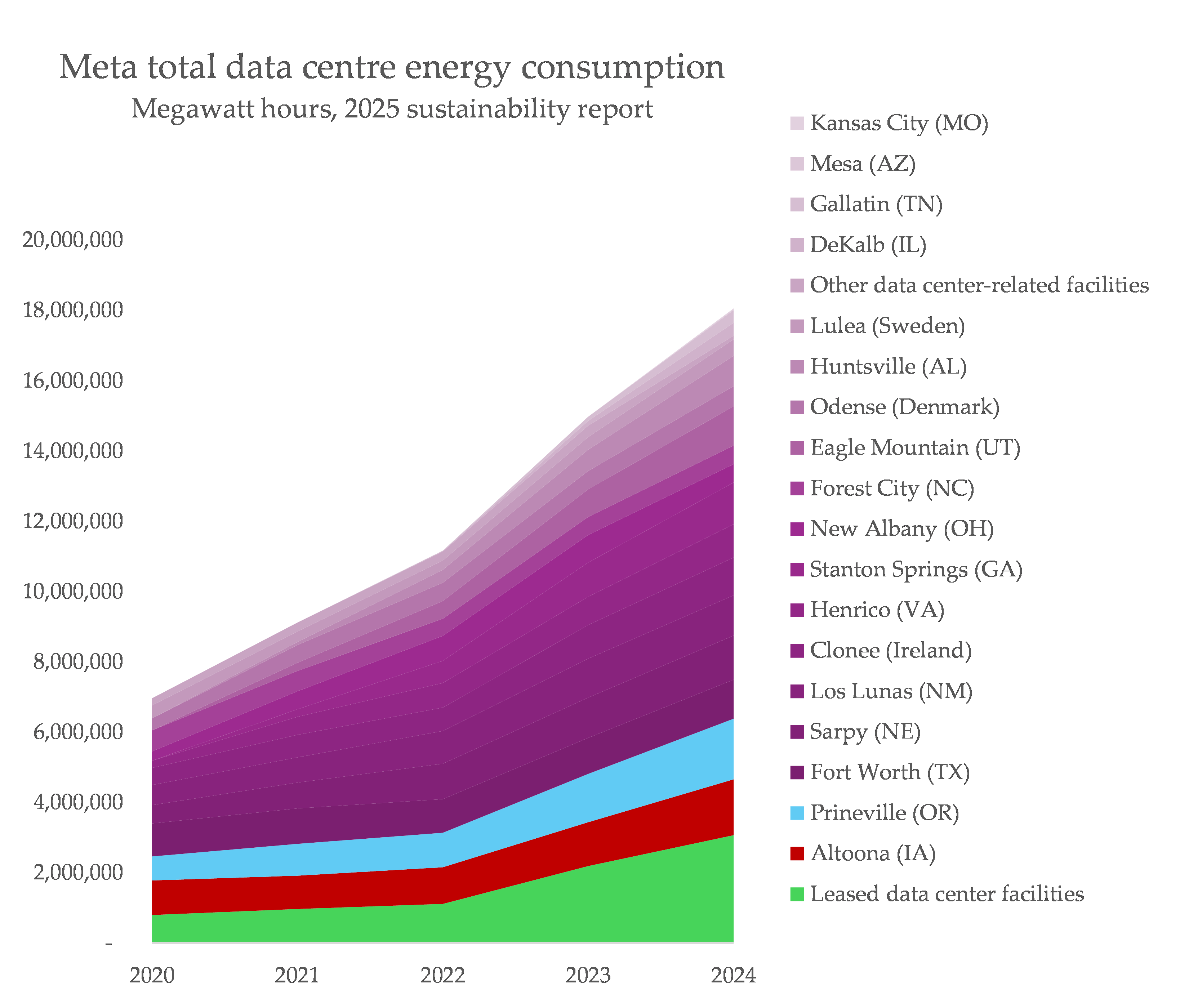

To its credit, Meta discloses information down to the level of individual data centres. You can see from this breakdown that most of its energy consumption rise stems not from its own construction of new data centres, but from a massive increase in leasing, and the on-site expansion of facilities in Iowa and Oregon:

Source: Meta 2025 sustainability report

Source: Meta 2025 sustainability report

This isn’t surprising. A few years ago, Meta was forced to fundamentally redesign its data centre capacity, packing existing facilities with mountains of additional hardware and even cancelling some builds halfway through to redesign them from the ground up. The company clearly hit a wall, shifting towards leasing data centre space from third parties, but it can’t do that forever.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1210971

This is likely all about to change: Meta is not just only building its own data centres, it is building its own fossil-fuelled power plants to run them. Analyst Nat Bullard recently revealed that Meta was the mystery name behind 600 megawatts of new fossil gas in Ohio. “Combined, there is a city’s worth of behind-the-meter, data-center-only power generation being built in one corner of one state”, he wrote. In Louisiana, Meta is partnering with Entergy to build a whopping 2,262 megawatts of new fossil gas (Entergy recently announced it won’t be hitting its 2030 climate targets thanks to its new fossil-fuelled power stations).

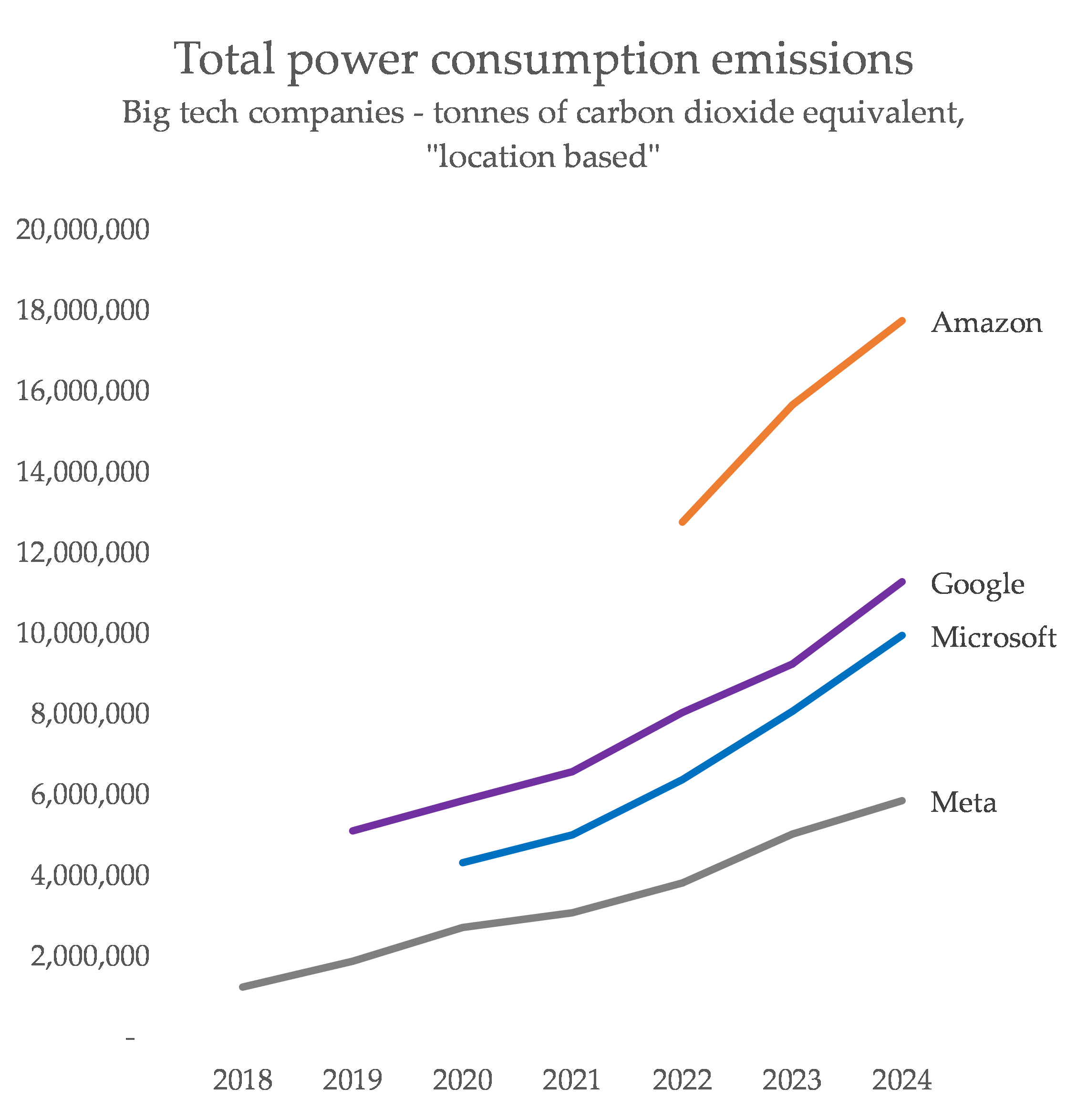

Meta attributes emissions to its data centres by first taking how much was consumed, and multiplying that by the emissions intensity of the power grid at the time it was consumed. It’s a rough estimate, but it’s the least bad way to guess what the climate impact of power consumption is. Meta, and some various other companies I’ve compiled, look like this:

Source: manual compilation of company emissions data

Source: manual compilation of company emissions data

As you expected, everyone is getting worse, fast. Meta, like others, has chosen to respond to this not by reducing its consumption, but by distorting the reality of how emissions are measured.

The current technique is pretty blunt. Meta purchases what are known as “renewable energy certificates”, or RECs. Every time a renewable energy facility generates a megawatt hour of energy, it sells a “certificate” of clean power output alongside selling the physical unit of electrical energy into the grid.

Meta, in buying that certificate, claims its power consumption had zero emissions. The logic is this: the decision to purchase that certificate was causally necessary in the coming-into-existence of that wind farm. If Meta hadn’t bought that certificate — if no-one did — no bank would’ve ever leant cold, hard cash to the developers due to the lack of that additional income stream, and there would be no wind farm.

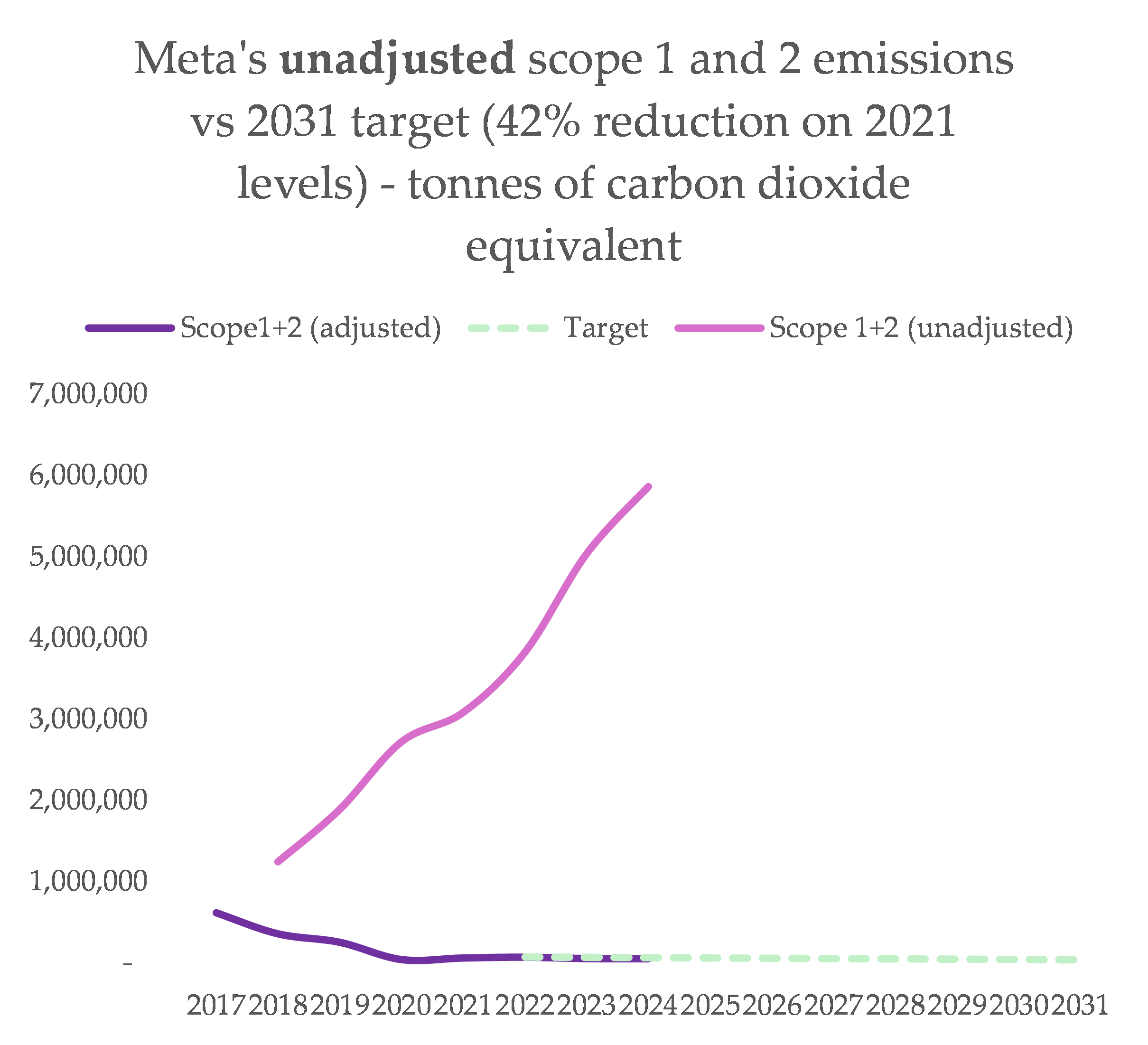

I know your head is spinning, but don’t let yourself be dazzled. This is just the weird cousin of carbon offsetting. They call this adjusted figure “market-based” emissions, and ensure that it’s this number that’s presented right up top in the headline figures (again to its credit, Meta discloses the “unadjusted” numbers clearly, where others obscure them as much as possible, such as Apple hiding it in auditor report footnotes).

By changing the basic reality of how it reports its power emissions, Meta’s compliance with its climate goals looks like this:

Meta isn’t denying climate change; nor is it being selective with its disclosures. It is taking a form of carbon offsetting and applying them not on top of reported emissions, but at the most basic structural level of emissions measurement.

This technique is beginning to hit a wall. There has been rising scrutiny of dodgy claims of zero emissions through the purchase of certificates (sometimes relating to ancient hydro power stations on the other side of the planet). Google, for instance, consumes so much energy it couldn’t sign enough power purchasing deals to fully zero out its power consumption emissions for its latest report. So where to next, now that the renewable well is running dry?

Stay tuned: part two will explore Meta’s current lobbying efforts to create a new way of zeroing out its greenhouse gas emissions.