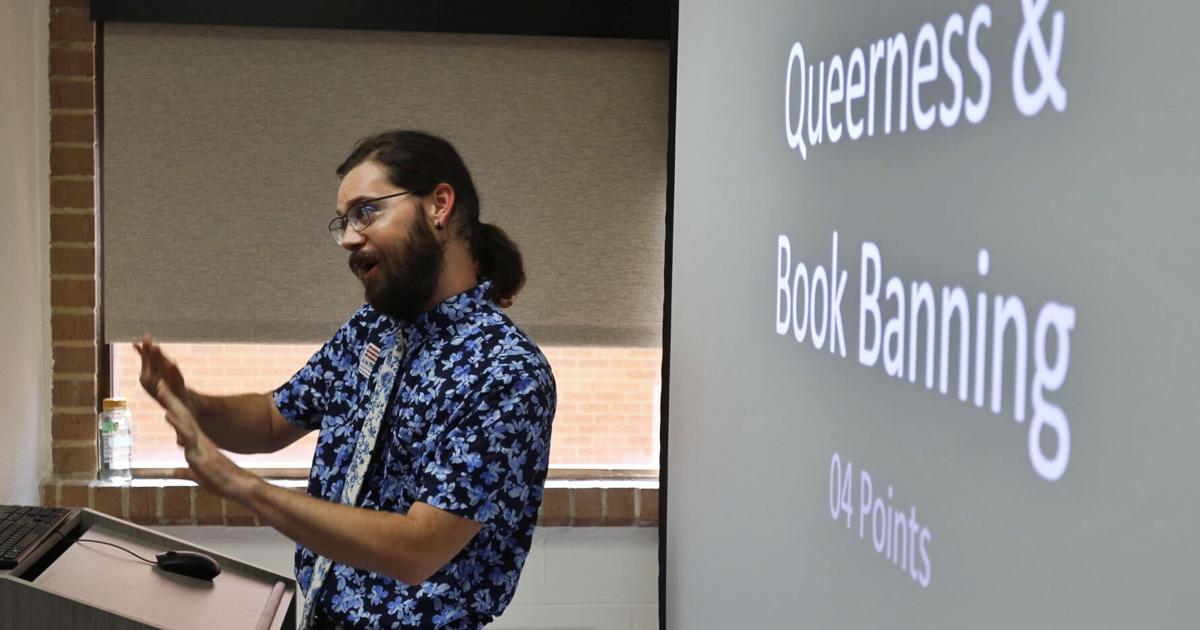

English lecturer Daniel Kasper presents a lecture on queerness and book banning during a banned books discussion Oct. 1 in Carlisle Hall. Kasper spoke on the Miller Test, Dorian Gray and Ulysses.

Photo by Elvis Martinez-Cartagena

As Banned Books Week approaches from Oct. 5 to 11, the English department hosted events to educate people on literary censorship and discuss its historical impact.

On Wednesday, Lonny Harrison, associate professor of Russian, and English lecturer Daniel Kasper spoke to students about examples of censorship in Soviet Russia and banned queer books. Harrison teaches a course on banned and censored works in Russian literature, and Kasper has taught a LGBTQIA+ literature theory course.

During the event, Harrison focused on the book “Doctor Zhivago” by Boris Pasternak, which acts as a demonstrative symbol of Russian books that faced censorship. “Doctor Zhivago” was written during a repressive police state in a time when art wasn’t just art, Harrison said.

English junior Rosie Mardini raises her hand to ask a question during a banned books discussion Oct. 1 in Carlisle Hall. Mardini asked about the legality of John Milton’s work.

Photo by Elvis Martinez-Cartagena

Harrison said literature in Russia during that period was almost sacred, with a moral weight to it. He said that novelists were beyond entertainers, serving as moral witnesses. Literature was used for insight and guidance, and reading banned books became an act of solidarity or even resistance.

“When facts are suppressed, a novel or poem can encode lived experience and smuggle it across generations,” he said. “It reminds readers that beneath the slogans, people still feel love, grieve and hope, and that truth endures even when speech is forbidden.”

English senior Logan McKelvey, who organized the event, said people aren’t aware how many popular books have been banned in the past, like “The Hunger Games” and “Twilight.”

Lonny Harrison, associate professor of Russian, speaks to attendees during a banned books discussion Oct. 1 in Carlisle Hall. There are about 23,000 book bans in public schools nationwide, according to PEN America.

Photo by Elvis Martinez-Cartagena

“Awareness is very important, and dedicating this week and having multiple events that kind of address and highlight banned works really helps emphasize that and gets that kind of outreach that impacts people,” she said.

Kasper said that English majors who go into teaching may run into issues with book banning, and that it’s good to have historical context when dealing with these situations.

One author Kasper spoke about was Toni Morrison, who wrote “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye,” both of which are often in the top 10 most challenged books, according to the American Library Association.

English lecturer Daniel Kasper wears a book ban sticker during a banned books discussion Oct. 1 in Carlisle Hall. Stickers and bookmarks were provided for attendees.

Photo by Elvis Martinez-Cartagena

Kasper said this could be because people are uncomfortable with reading about the reality of sexual exploitation under slavery in “Beloved” and challenging themselves to confront other difficult topics like pedophilia and child sexual abuse in “The Bluest Eye.”

When banning a book, the standard that is followed is called the Miller Test. Kasper said that the words used in the Miller Test can be confusing to decipher the true meaning of, which complicates the process of determining what is considered obscene.

“Not only are the people not really reading the books before they’re objecting to them,” Kasper said, “they’re still doing the picking out dirty words bit and deciding that just because part of the work is challenging or sexy or whatever, therefore the entire book falls and becomes obscene.”

Lonny Harrison, associate professor of Russian, speaks on banned Russian works during a banned books discussion Oct. 1 in Carlisle Hall. Harrison spoke about the consequences that authors have faced when writing books considered inappropriate.

Photo by Elvis Martinez-Cartagena

When asked if there is any hope for improvement, Kasper said political change is certainly possible.

“It used to be better than it is right now,” Kasper said. “But if it used to be better than it is right now, it’s possible to get back.”

Harrison said even though we don’t have a literary culture anymore, there are still powerful modern works, and it’s beneficial to be historically informed.

“Literature calls power to account and can be seen as symbols of truth and courage,” he said. “I think that can be true even in a society where we don’t tend to read that much literature anymore. Still, we can learn from these remote periods in history.”

@hud4qureshi