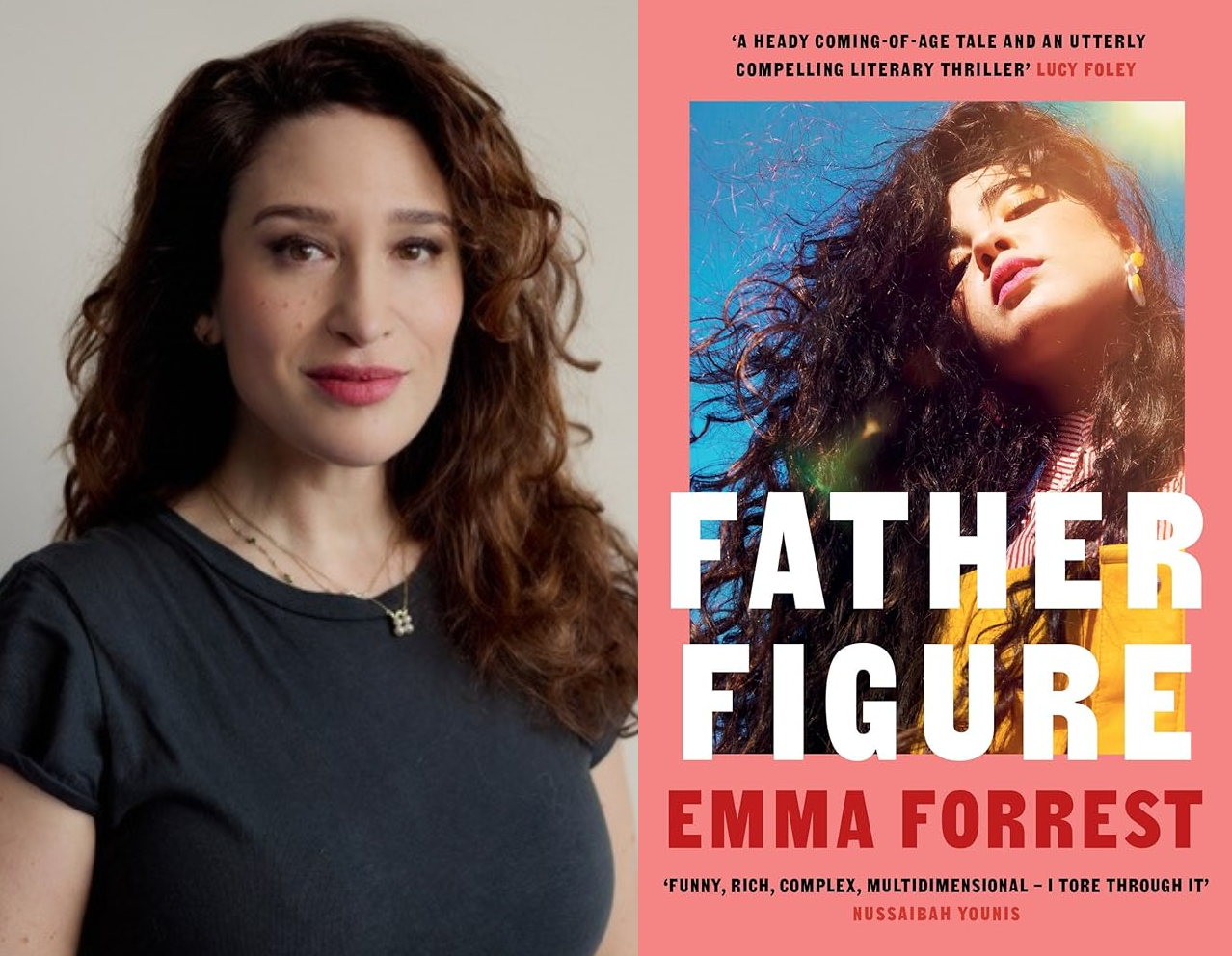

The latest novel by British author Emma Forrest, Father Figure, is arguably the greatest work of Jewish literature in decades—at least, that’s according to The CJN’s opinion editor, Phoebe Maltz Bovy, who gave a glowing review to the new release on Sept. 29.

But across the pond, the book has received a muted reaction. It hasn’t been spotlit in any British book fairs; it’s been largely ignored by domestic literary awards; professional friends who’ve helped promote, and even written forwards for, her past works have largely ignored this one.

What makes this latest book different? It is unmistakably, idiosyncratically Jewish. Combine that with the growing antisemitism that’s erupted in the United Kingdom since Oct. 7—which culminated in a lethal terror attack in Manchester on Yom Kippur—and it’s hard for Forrest not to think her apolitical work of fiction has suffered from her personal cultural identity and a broader political climate.

Forrest joins Maltz Bovy on the latest episode of The Jewish Angle to discuss her novel, along with its deep inception and quiet reception. Forrest describes the real-life inspirations behind her boarding school setting, including her own encounters with Harvey Weinstein, how they influenced her characters, before discussing the recent tragedy in Manchester and how her country’s small Jewish community is reacting.

Transcript

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: This is Phoebe Maltz Bovy, and you’re listening to The Jewish Angle, a podcast from The CJN. Very, very Jew. So today we are going to have a little bit of a diversion into the world of fiction. So Emma Forrest, who’s my guest today, is an English author, filmmaker, and most importantly, per her website, podcaster, amazing. Her latest book, Father Figure, is really the best Jewish novel that has appeared in decades. It’s like something where I’m thinking like the publishing term comp titles, so similar books. I’m thinking like Portnoy’s Complaint or Fear of Flying. Like, it’s that kind of Jewish novel. I want North American readers to know about this because it’s like this is the Jewish novel that I personally have been waiting for. But it’s also set a decade ago and very much of this world. So it doesn’t feel like it’s some sort of historic thing that feels dusty and of another time. It’s very much of this moment. Emma Forrest, welcome to The Jewish Angle.

Emma Forrest: Thank you so much for having me.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: So how did you come up with the idea of a story about an—I don’t want to say ordinary, because Gail is not ordinary, but—of an everyday Jewish schoolgirl crossing paths with an oligarchy-type figure?

Emma Forrest: Because when I moved back to—I lived in America for a long time. So I lived in California, I lived in New York. I was away for 20 years. And my mom’s American, and when I came back to the UK, I walked past my old school, which was a private girls’ school that I had had a bursary scholarship to, and it looked completely different. And I called my sister and said, what happened to—I’m not gonna name the school—what happened to it? And she said, hadn’t you heard? And then she named an oligarch, whose name you would know, and said he started sending his daughter there, and he’s bought all the buildings that surround the school, and he’s put an armed guard on the gate of the school. And I was like, oh, my God, this is a novel. Because if I had been there at 16, I would, knowing myself at that age, have tried to inveigle my way into his life via his child, obviously. And I’ve always had a real interest and soft spot in any book or film, any piece of art that uses the archetype of the stranger who arrives and disrupts an entire family’s life. A novel I really love in that vein is The Accidental by Ali Smith. And a film that’s incredibly important to me, and actually I keep finding now from quite a few novelists, is Teorema by Pasolini, which I guess is Teorema in Italian by Pasolini starring Terence Stamp, who recently died. And it’s about a stranger who arrives and makes love to each member of the family and drives each of them crazy. And you don’t know if he’s God or the devil. And then he leaves.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: So I should say listeners have not maybe necessarily yet read Father Figure. They should go do that. Gail is this teenage girl who encounters, via the child, the teenage child of Ezra Levy. She, you know, encounters this oligarch-type guy, but she also brings out something to do with his Jewishness in him in this complicated kind of psychosexual way that’s hard to… like, I can’t describe it. I mean, I just want to talk a little bit about Ezra. Just because the Western canon is full of men like that, right? These, the Jew, you know, how did you decide to take somebody like that and make him, like, a man?

Emma Forrest: I looked up how many of us there are here. It is tiny. It’s like 250,000 Jews in the United Kingdom, 4 million Muslims in the United Kingdom. We’re microscopic. So hyper-aware. Probably the way people were when Summer of Sam happened. Like where you find out David Berkowitz is Jewish and you’re like, for Frigg’s sake, like, this is not helpful. So there kept being these British figures through my childhood of whom I was very aware, who just felt profoundly unhelpful, like Robert Maxwell, Philip Green, who owned Topshop. There’s a very famous figure here, I don’t know if he translates there, called Sir Alan Sugar, who owned one of the big football—I think he did, was chairman of Tottenham Football Club. And these just like awful sort of Nazi caricatures of Jewish billionaire, like hideous Jewish billionaires. And the only comfort I’ve had recently is the only person who looks remotely like them. I noticed, and this really struck me, is Mohammed Hadid, the father of Bella and Gigi Hadid. If you want to tap into the idea that we come from the same place. Right. You know, the only one who’s presented such an archetypal, like, gross Nazi figure as those men is him. And so humanizing. All the Jewish men I know are so benign and beta, so the idea of like an alpha Jewish male is anathema for me anyway. Pretty much the men closest in my life were my dad and, I don’t know if you know, the great investigative journalist John Ronson, who wrote The Psychopath Test and The Men Who Stare at Goats. I grew up with him. So those are the two guys I knew, and they’re very, very gentle. So I’m fascinated by, what if a Jewish man was tough? I’m like, what? What are you talking—how could that be? You know, the Israeli Cabinet would disprove that image. But yeah, it certainly. I grew up with this very sort of beta idea of the Jewish male. So I think that’s why I wanted to know what are the layers and the ribbons and the flavors? Insights. Someone who presents as very alpha but whose main vulnerability is wanting to be part of the British establishment.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I just—the girls’ school stuff. I went to a girls’ school in Manhattan when I was quite young and it all just—it felt just so beautifully described. I mean, the stuff about everybody having at least a bit of an eating disorder seemed pretty true. But also—but I wanted to ask you—so Dar is Gail’s mother in the book. She and Gail are both such full characters and it’s such a realistic mother-daughter relationship. I especially like the part where Dar thinks she’s going to help out by getting Gail invited to a party, and it just turns out she’s read everything wrong.

Emma Forrest: Oh, yeah, yeah.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: So talk a little bit about how you write the mother-daughter, getting both sides so…

Emma Forrest: Well, I guess because I’ve been both. You know, I’m a single mom, and my daughter’s coming into the cusp of adolescence. I always write about the things that are scaring me in order to make them safe. And it usually works. And there was just an incredibly bad decision when my sister and I were kids that we would be moved from the state school, which in Canada. Is that public school?

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: You know, public school, yeah.

Emma Forrest: Right. Where we would be moved from a state school by my grandfather, who was able to afford to put us in a private primary school, which I guess is—What do you call it when you’re little? When you’re like, elementary school? 8, 9, 10. Elementary.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I’m probably getting it wrong, but yeah, go on. Yeah.

Emma Forrest: He paid for us to go to elementary school privately, and we were the only Jews. And there was one black kid who I think was the son of the Nigerian diplomat to England. And my sister’s class was okay. My class was really anti-Semitic. And they were so young. They were like 8, 9, 10. It was coming from the parents, which you figure out, but also explicitly, they would say. My mother says it was actually the school that Catherine and William, the now King—almost King—ended up sending their kids to. In my class, Winston Churchill’s great-granddaughter was in my class with me. One of Lady Diana’s bridesmaids was in the class.

It was the wrong place for us, and it really scarred me. I remember there was a particular bully who was the daughter of a Greek shipping magnate. She would do all this stuff about, you know, “Don’t you feel bad for killing Christ?” And she would call me the N-word. Someone has to really want to say the N-word to say it to someone who, like, has curly hair and that’s it. It took, honestly, until I was in my mid-20s and one day just sitting on a bus and thinking, hang on. On the ethnic scale from, like, Nubian to Swedish, Greek and Jew fall in the same place. So what? This wasn’t even appropriate bullying. This is just crazy. I think I realized quite late how deeply ingrained that period and that mistake of sending us there was—of trying to make us sit alongside the British Establishment. With my daughter, I’ve gone completely the other way. She’s only been in state schools. In public schools, they’re completely mixed. They’re heavily Muslim and Jewish. Her local school—because we’re in North London—and it’s been night and day.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: That’s interesting. I have so much to say on this. Oh, my goodness. Yeah. I also went to a school of that sort until high school, from when I was 5 to when I was 13. I don’t think it was quite the same in terms of Jewishness as it would have been in England. But it wasn’t entirely different. I did hear the “Jews killed Jesus” thing. I remember thinking that to be attractive, you had to basically look like Claudia Schiffer. I was shocked when I went to college in Chicago that women who looked like me were not considered repulsive for not looking like Claudia Schiffer. Men who had grown up around women who looked like that found women who looked like me exotic in a good way. It was a very confusing time. There are a couple of connections to Father Figure that I want to talk about. There’s this one amazing moment where Gail is in a police car with a man, and it feels like you’re in this very modern novel, where people are from marginalized identity groups. There’s a gay man who’s been picked up for public sex, and he says he wouldn’t, though, with George Michael. And why is that?

Emma Forrest: He’s too far.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: It’s just like this amazing punchline. I was thinking about that when you were talking about the Greek shipping magnate.

Emma Forrest: You’ve mentioned your writing, and you’re completely right. It was absolutely significant that George Michael actually talks about his Jewishness on Desert Island Discs, finding out fairly late that his mother was Jewish. It explains to me a great deal about what we love about George Michael. Despite his very traditionally macho, almost Tom of Finland look, this anxiety, he has a vulnerability to his work, like a neurosis.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Yeah.

Emma Forrest: I found it very moving to realize that someone I love that much had realized that about himself. He’s there for a reason.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: The scene that is going to be like anybody who’s doing any kind of Jewish Book Awards—not that you shouldn’t get the Mainstream Book Awards too, but the Jewish Book Awards, specifically—is that scene in the Anne Frank House.

Emma Forrest: Yeah.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Are you familiar with the Seinfeld, Schindler’s List make-out?

Emma Forrest: Yeah. I took my daughter to Anne Frank House, and I didn’t know if I had the courage to write this down. So I wrote it down in a sort of satirical way in the book. I was struck by what a lovely place it was with a lovely view and light, if it wasn’t being used for what it’s been used for. The shiksa stepmother verbalizes that she wants to make an offer on it. But as you walk through it single file, you can’t really tell what’s going on with the people behind or in front of you. I thought this would be a really good place to have an illicit touch.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I found the kiss aspect very subversive. It subverts two different tropes: the Jewish man aroused by the shiksiness of a non-Jewish woman, which you get in things like Woody Allen, Philip Roth, Seinfeld. It’s old and hasn’t gone anywhere. There’s also the 19th-century trope where a non-Jewish man is going for the exoticness of a Jewish woman. This subverts both, and it’s another part where Ezra is saying that a certain type of man would find Gael attractive, but he doesn’t. He’s telling himself, yeah, this is a pretty big one to drop.

Emma Forrest: One of my good friends who I’ve known for decades grew up with Georgina Chapman, who was the wife of Harvey Weinstein. There were times I was around Harvey, and he just had no idea how to interact with me because of my Jewishness. I knew that’s what it was about. He could not make any sense of me. There are slivers of those experiences with Harvey in how I thought Ezra might react to Gail.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I wanted to ask you—Father Figure is not a political book promoting any party or ideology, but it doesn’t shy away from contentious topics. What was it like writing a book that deals so directly with Jewish identity and British Jews’ differing views about Israel in this moment?

Emma Forrest: When you said all the wonderful things about this book, it brought tears to my eyes because this book has been rejected. It’s the first book I’ve written that hasn’t been accepted into any British literary festival. None in England; I did one in Scotland. There’s no foreign translations; it’s not on any of the tables in bookstores. People who blurbed my other books or supported my other books publicly, who aren’t Jewish, have not responded. It’s been very dispiriting.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Do you think it’s just the amount of Jewish content, or is it the fact that it is not taking a side in some unambiguous way?

Emma Forrest: I think people are really scared. One of the great supporters of it is a wonderful writer called Naseiba Yunus, who wrote a great book called Fundamentally a Great Novel. And she was not just a practicing Muslim but a very seriously practicing Muslim until she sort of moved away from religion entirely. She wrote a novel that’s comedic about being sent to Iraq to de-radicalize ISIS Brides. It is the most brave, amazing book, and she has the bravery and the complexity to have read Father Figure and gone, “I love it.” And people are scared. I’ve had friends, and these are all people who are not Jewish. I’ve asked, you know, when they’re fundraising for Gaza, “Is it possible to mention the hostages?” Certainly, the one time a famous person mentioned the hostages, they got so many death threats that they were scared, which I understand. A public figure told me straight, her management said she can’t speak about them because it will damage her career. That’s where we are. People like things to be black and white. If you want to start at a really basic level, the way I try and go in is with all the things you could say legitimately to criticize Israel, and there are a lot of them. The idea that Palestinians are brown and Israelis are white is crazy. That’s not the truth. I’ve said over and over, publicly on my Instagram, that in my opinion, the reason those hostage posters keep getting ripped down is that when you have 250 faces, you’re going to have to guess that’s a fairly accurate representation of Israeli society. A couple of them are white or white-passing. Those are brown people because they either come from roots that were always there or they come from the places they were expelled from for being Jews, you know. That completely unanchors them and confuses them, and yeah, it’s been dispiriting but not unexpected, but that doesn’t make it easier.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I think something so interesting in Father Figure is that it’s Gail, the younger person, who is sort of taking the. I don’t want to say pro-Israel position. She’s not pro-settler, but she’s taking more of a…

Emma Forrest: That’s the influence of Hanif Qureshi, who has written a lot in his books about the immigrant experience. The next generation being more conservative than their parents. Also, we all, as much as we love our parents, hate a part of our parents. So you react and are whatever they are not. That’s where that comes from for Gail. But yeah, I think the archetype of, especially with single parents, the younger generation being more conservative, is fairly accurate, actually.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I just want to talk to you about your reactions to the horrific attack at a Manchester synagogue. And also just to… yeah, what has changed, really, maybe since October 7, 2023, in British Jewish life?

Emma Forrest: Oh, my God, it’s so much worse. It’s so much worse. Again, a really good friend, and when I say a good friend, I mean people who check in with me, not just on the anniversary of October 7th, like to see how I’m doing, but who’ve been very open that they cannot say anything publicly. A friend who was like, “Of course I wanted to post something on Instagram after the synagogue attack, like the way you would if it happened to any other group, but I just feel like people decide it means something, and that it would damage my work.” And she’s not wrong. We were in services, and we all had our phones off, obviously. Then we came out and were told, “Move, move, move. Do not congregate. Keep going.” My daughter was right on the cusp of. She’s 12, so she’s right in the place of, like, “I’ll do what I like.” And she’s like, “Why do I have to move?” And I remember I looked around, I was like, “Because people come to synagogues to kill Jews.” And then we headed home and turned on the phones, and there it was. Life’s been really bad. When October 7th happened, my kids were just at the end of elementary school. I remember a white Irish family who never spoke to us ever again. Not only did nobody say, “This is awful. Are you okay?” We just wanted that. There was never that beat. I’m sure this happened in, not just in the UK, everywhere. Everyone in my publishing life, only my book agent is Jewish; no one else is. The woman who started my career, who first published me on October 7th, was on Instagram organizing a fundraiser for Gaza. There just was no beat or moment where she or anyone said, “We’re really sorry this happened. This must be incredibly traumatic.” There were two British feminist writers who did go out of their way on their Instagram and said, “There is no historical context that makes rape as a tool of war acceptable.” Not another person that I can think of. No other female writer said that.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Do you remember which writers that was?

Emma Forrest: Yeah, I do. And the awful thing is that I want to name them because I’m so grateful to them. I also wonder if me naming them harms their career. It was Terry White, who’s a great writer, and Polly Vernon. I remember a couple of months after October 7th, I was nominated for a literary prize for the first time. Weirdly, for the first time in my career. It was so exciting. Now, four judges and waiting to see. I didn’t win, but in the process of waiting, I went on the Instagram of one of the four judges. She was not just posting anti-Israel stuff, which is, you know, par for the course. She was posting, you know, “Israelis are doing this to harvest the organs of Palestinians.” She was posting recipes she would use if Hamas ever came to her house so she could cook them all dinner.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Oh, boy.

Emma Forrest: And that was one of the judges of my work, in which, you know, my Jewishness is always part of the story. I talked to my agent and said, “Is there anything we can do?” And we just kind of, there’s nothing. There’s nothing that can be done. We didn’t say anything; we didn’t want to be. We get told every single time that we’re playing the victim. All I can say is that there’s a lot of very left-wing, white English people who’ve been terrible, and probably the people who’ve checked in on me the most have been my Muslim friends. They’ve really gone out of their way, so that’s meant something for sure.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: On an upbeat note about your book, is it going to be a movie?

Emma Forrest: So, that’s an interesting thing too. It’s actually, it’s been optioned as a television series by the people who make Slow Horses as a miniseries. That fascinated me because. So the book, when it was optioned, the book hadn’t come out yet. Of all my books, it’s the one that got the most offers. There was a bidding for the screen rights to this book. I’m fascinated, too, given the experience I then had with publishing it being so different and having no support or feeling like I had no support, even though it got tremendous reviews. I had, you know, The Guardian wrote it was amazing. The author, Jonathan Coe, picked it as his book of the summer. There was something in it that didn’t actually. The woman I ended up going with was Greek, and she told me that she recognized in the book, like, all the dynamics were stuff she understood and could relate to. I think that’s also true in the United Kingdom, that it kind of doesn’t matter what minority you’re from. Ethnic minorities in Britain recognize a lot of the same stuff, you know, about being here.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Yeah, it’s interesting. I mean, being American and in Canada, and now on paper, Canadian, culturally, probably pretty American. I do sometimes think just that it has nothing to do with. Well, a little to do with my personality, because I’ve chosen to become an opinion writer. But, like, I just. And the whole sort of, like, thing of being evasive, whispery, apologetic about Jewishness—just. I wouldn’t even think to do this. But I don’t think it’s so much about my character. I think it’s more about, like, I grew up in New York City, where this was just not a remarkable thing about me. And in Canada, I see the British way a bit like, it’s a. It’s somewhere in between, maybe.

Emma Forrest: Yeah.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: So I know what it is. I more often see it in some British Jews. Like, that’s sort of like what Ezra does of the sort of, like, not wanting to draw too much attention to the Jewish. It’s like, I see it a little bit in Canada, it would be hard for me to imagine it in the States. It’s just not something. It’s not a way of being that really exists in the States.

Emma Forrest: Well, there’s also, like, you know, I don’t know, off the top of my head, two incredibly rarefied British Jews would be the director Sam Mendes and Stephen Fry. And you wouldn’t. You just. You wouldn’t know that because that they’re Jewish, because what they read as is very upper class, you know, very, very rarefied. So that stuff that. Having an American Jewish mother and an English Jewish father, I always see that divide over and over. My dad was sent to boarding school when he was really little, in order specifically to become less identifiably Jewish.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: I could ask you questions about all of this, truly, all day and for weeks and years on end because I have so many things to talk about. It is Hillerford podcast, so I’m going to have to thank you so much for coming on The Jewish Angle. I’m going to have to again recommend Father Figure. And where can people find your work apart from your book?

Emma Forrest: Well, so Canada’s been a good market for me with my memoir, Your Voice in My Head, which came out 10 years ago and has always sold pretty well there. So you can get that. And if you’re ordering from the UK, Father Figure Blackwell’s deliver for free. So I recommend Blackwell’s.

Phoebe Maltz Bovy: Excellent. Thank you so much for coming on.

Emma Forrest: Okay, thank you for having me.

Show Notes

Credits

- Host: Phoebe Maltz Bovy

- Producer and editor: Michael Fraiman

- Music: “Gypsy Waltz” by Frank Freeman, licensed from the Independent Music Licensing Collective

Support our show