Michael Hogue

The city of Dallas will soon evaluate partnering with local developers Mike Ablon and Mike Hoque on an ambitious plan to rejuvenate Bank of America Plaza. The Dallas City Council will begin examining it today in a committee meeting. The full council votes later in the month.

The matter amounts to a referendum on downtown — hopefully not a requiem.

I use the term Daltroit regularly. I do so in hopes of sparking a conversation that the city is at a tipping point. Ablon doesn’t like the term. We are a contrast: I’m the glass-half-empty guy. He sees opportunity.

I’ve worked with Ablon a few times and have known him for more than 20 years. Everyone likes his energy and knows he’s smart. He’s passionate about all things Dallas with degrees from the University of Texas and Harvard. He’s trained as an architect and knows development.

The city should be happy to have a partner like that because reimagining Bank of America Plaza at 901 Main St. is a huge project. He says, “I only work in D-FW. I love this place; I know this place.” Contrast that with developers who say they will never do a project in the city of Dallas again.

Opinion

They first met when Hoque was a tenant in an Ablon’s building in Addison. A Bangladesh native, Hoque has helped revitalize the downtown food scene with Dallas Chop House, Dallas Fish Market and Wild Salsa. He’s also amassed large tracts of land around City Hall and in the Cedars

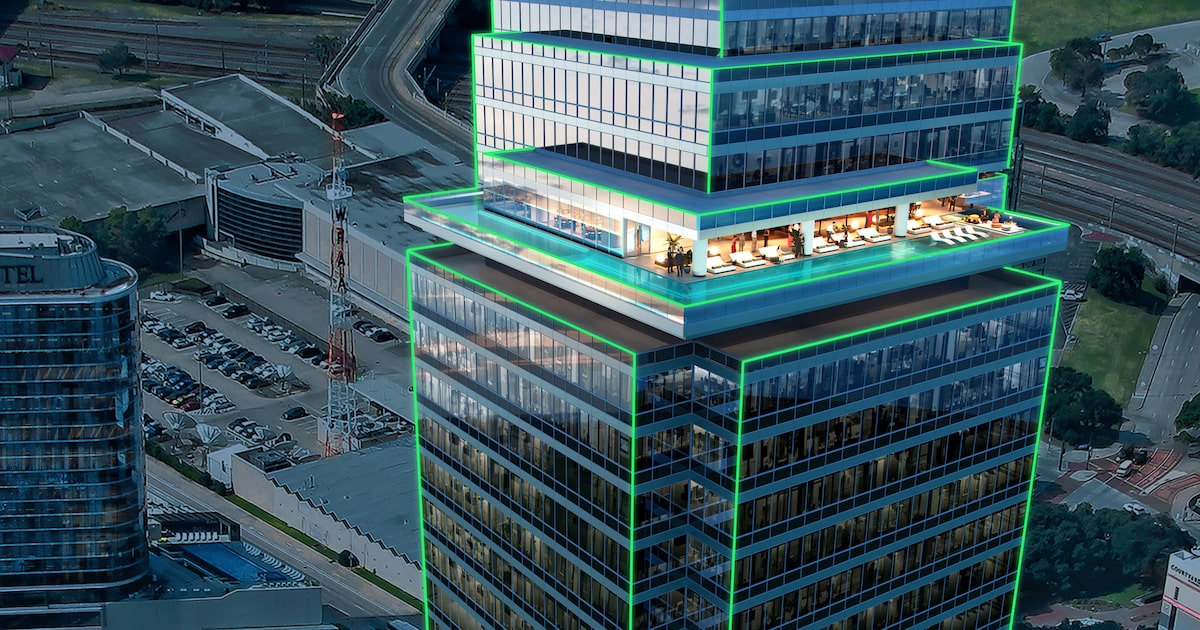

The duo is poised to take on the challenge of remaking the 72-story Bank of America. It remains a giant green beacon (although with LEDs that iconic green can now change colors).

And how could it not be a beacon? It’s the tallest building in the city and the third tallest in the state. What kind of beacon it is going to be in the future is the question.

The Dallas Morning News’ architecture critic, Mark Lamster, agreed: “Dallas has lots of mediocre mirror-glass towers. Bank of America is a big step above that cohort, a pristine neo-modern tower.”

Prominent local architect Tipton Housewright said: “The building is an important part of our skyline, but not very friendly to the street. … The development team is making good choices and doing what’s right.”

Unfortunately, the building is a product of its time. Constructed from 1983 to 1985, it harkens to an era where employees reported to work wherever their boss deigned to put them.

Now, employees want curated amenities and choices. Employers must meet those demands to assemble the best talent.

“In its current state, the building is unleasable,” Ablon said. The lack of dedicated parking and amenities cripples its chances in the market. Yes, parking matters when it comes to office buildings.

The development team plans to add ground-floor retail, dining and about 300 upscale hotel rooms to fulfill the tenant needs and create a destination.

Ablon has done this before in downtown, redeveloping Ross Tower. He’s also hit a home run in the Design District. Most people in Dallas, even serious real estate people, thought he was crazy to invest on the west side of Stemmons. Former Dallas City Council member Ed Oakley had ensured a progressive zoning ordinance for the area and a Tax Increment Finance (TIF) district. Only Ablon and Oakley believed in the dream. It came to fruition, growing the Dallas tax base significantly.

Now, Ablon wants the city to back his plans to redevelop the Bank of America and provide a TIF. In the inside baseball world of municipal funding, TIF arrangements amount to developers receiving their own tax money back once they’ve increased the taxable amount of their property. If Ablon and Hoque win, they get paid. If they don’t, then the city is not out any money. The pair plans to invest $409 million into the hotel and garage in hopes of obtaining about $98 million in TIF funds — call it a rebate of their own tax money.

Some critics want more information on where the team is getting their funding. I never worry about that. It is a problem for closing and not for public debate. Ablon has plenty of proof that he can close big deals.

Detractors have concerns that Hoque lacks the requisite track record on successful projects of this scale. They think he’s just assembled land and is a speculator.

Ray Washburne, a noted local developer and one of the owners of the Highland Park Village, owns property adjacent to proposed redevelopment. “My concern is it being properly urban planned to integrate into the future of the neighborhood,” Washburne said. He is concerned that the new parking garage will create a “giant block” for pedestrians from the new convention center.

Others I spoke with don’t believe anything will be built on top of the garage. This has happened before with the abandoned Reunion Arena garage that is sandwiched between Houston Street and Jefferson Boulevard viaducts.

Ablon thinks the doubters are “looking backwards. “I’m looking forward,” he told me. “If I don’t do this, and the city doesn’t do this, how do we expect people to want to be in downtown Dallas?”

That’s the right question. How do you get people to go back downtown? For 15 years, I had an office in Founders Square that overlooked Bank of America. I rarely ventured over because there wasn’t anything drawing me there. Since then, I’ve moved my business to Oak Lawn. My employees were thrilled.

The cost of construction for the building in 1985 was $146 million. It would cost more than a billion to build today. These older buildings have tremendous value, if they get into the hands of someone who can do something with them. We will not see buildings of this scale built downtown; they are simply too expensive. As such, we need them to be revitalized.