Fre’Drisha Dixon can still recall the laughter that once spilled across the playground of the now-shuttered Clyde Woodworth Elementary School in Inglewood. Just as clearly, she can conjure up the loud banging of the bulldozers that plowed through the school’s classrooms last year.

Today, both sounds are drowned out by talk of turning that barren land and five other recently closed schools across the historic Black city into parking lots and luxury housing. They’re promises wrapped around a $2 billion arena billed as the world’s “greenest,” but built on the erasure of a community, she said.

As the National Basketball Association’s Los Angeles Clippers finalized a deal to build the Intuit Dome in 2020, experts warned that arena construction plans were “eerily similar” to the highway projects of the mid-20th century that uprooted Black neighborhoods across America.

The warnings became a reality.

When the dome opened last year, it became the centerpiece of preparations for Los Angeles’ third Olympic Games, anchoring a cluster with SoFi Stadium and the LA Forum. For city leaders, the new entertainment district and the $7 billion Olympic Games offer a spotlight for waves of investment. For thousands of Black renters and homeowners, they signal another chapter in a long cycle of rising rents, displacement, and environmental burdens.

“Our city got sold out,” said Dixon, a lawyer and community activist. “Inglewood residents — Black residents — are the casualties here.”

Black Inglewood residents trying to hold on feel stuck on the losing end of a sprawling deal between some of the world’s most powerful people. Six years since a deal was struck to build the dome, the arena’s political and financial backers find themselves entangled in a sprawling federal fraud investigation — one that stretches from a $2.3 billion international tree-planting scheme, through the corridors of California’s political power, and all the way to the billionaire owner’s suite. The reverberations threaten not just the Black community trying to hold on, but also ripple out to the world’s stage, ensnaring a presidential hopeful, an NBA superstar, and the lead-up to the second-most-watched event globally.

The most profound impacts of the Intuit Dome’s rise can be found in daily life. Traffic gridlock and relentless event schedules have made routine activities, from grocery shopping and evening strolls to visiting elderly relatives confined to their homes, feel like navigating a maze, residents said.

“Our city got sold out. Inglewood residents — Black residents — are the casualties here.”

Fre’Drisha Dixon, lawyer and Inglewood community activist

Local businesses that once thrived on community support now face dwindling foot traffic, as game days and concerts divert visitors directly to corporate chains near the arena, bypassing the small shops and restaurants that are an integral part of Inglewood’s cultural heritage.

“You see folks waiting in line for hours to get into events, leaving trash everywhere,” Dixon said, “but there is no money trickling down into the local businesses.”

Lawrence Scott, the former owner of Scottle’s Gumbo and Grill, agrees. Last year, he described how, just a month after the Inglewood Entertainment District opened, the building his restaurant was located in was sold and he was forced out.

“If they hadn’t opened the stadium, I’d still be there, I know that for a fact,” he said.

Inglewood carries layers of Black history, from families who built tight‑knit neighborhoods during the Great Migration to generations who shaped its culture, churches, and music scene long before the world’s most expensive sports arenas rose up around them. (Courtesy of Intuit Dome Communications Team)

This cycle was accelerated in 2019, when Gov. Gavin Newsom — who has received over $1 million in campaign donations from the Ballmer family, the owners of the Intuit Dome — fast-tracked the arena’s environmental review. The move mirrored a similar shortcut for SoFi Stadium. The governor shortened the public comment windows and shielded developers from lawsuits over air, noise, and carbon impacts.

To quiet critics, Steve Ballmer, the 10th-richest person in the world, and city officials pointed to social investments, including new EV charging stations, 1,000 new trees, and a high-profile carbon offset partnership with the fintech company Aspiration. However, that company is now under federal investigation for hundreds of millions of dollars in fraud, accused of failing to deliver its promised offsets.

Investigators are also scrutinizing allegations that the Clippers funneled $28 million through Aspiration for a no-show endorsement deal with star Kawhi Leonard.

Black residents said the pledges to “make Inglewood more green” feel hollow now.

“Our businesses and schools are closing, our people are leaving, and nothing about that feels sustainable,” Dixon said.

Governor Newsom’s office acknowledged a request for comment but did not offer a response, and the city of Inglewood and the LA Clippers did not respond to any requests for comment.

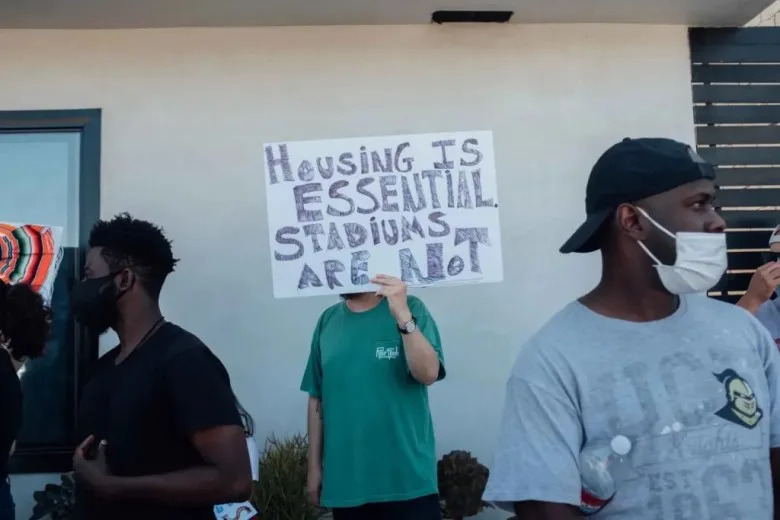

Inglewood residents, teachers, and students protest outside SoFi Stadium after plans to close down local schools were announced. (Courtesy of Fre’Drisha Dixon)

Inglewood has been at a crossroads before

Inglewood had been here before, and successfully beat back Walmart when the community was much more uniformed. In the early 2000s, the city blocked Walmart’s plans for a massive supercenter on the 60-acre site that is now SoFi Stadium. It was one of the nation’s most prominent local rejections of big-box retail expansion, and served as inspiration nationwide.

At the time, the Los Angeles affiliate of the A.F.L.-C.I.O. said Inglewood’s successful fight showed what was possible as billion-dollar corporations attempted to bypass regulations. “It will become the battle royal for all of organized labor in the United States,” the union said.

Grassroots coalitions of residents, church groups, labor unions, and small-business owners mobilized against the supercenter, fearing it would undercut local businesses, depress wages, and contribute to traffic congestion, much like the stadiums have. In 2004, voters overwhelmingly rejected a ballot initiative that would have allowed Walmart to bypass city oversight, thanks to strategic outreach, door-to-door campaigns, and the alliances.

“We saw the forces of gentrification as a threat to our community’s well-being every bit as dangerous as gangs and drugs,” wrote Inglewood resident Erin Aubry Kaplan in 2023 about the city’s battle against gentrification.

But with the neighborhood change, residents told Capital B, so has the fight.

Despite this earlier success, Inglewood’s community activists were unable to block the much larger and more politically connected Inglewood Entertainment District. Several factors contributed to this outcome: City and state officials touted the district’s promises of massive economic investment, job creation, and tax revenue, while influential sports and real estate interests, led by billionaire developers, enlisted powerful lobbying support. Unlike the Walmart fight, the local government directly negotiated concessions with the developers.

Inglewood renters fight for rental protections amid rising rents. (Courtesy of the Lennox-Inglewood Tenants Union)

As a result, concerns about rising costs, displacement, and congestion were outweighed by government and business promises of progress.

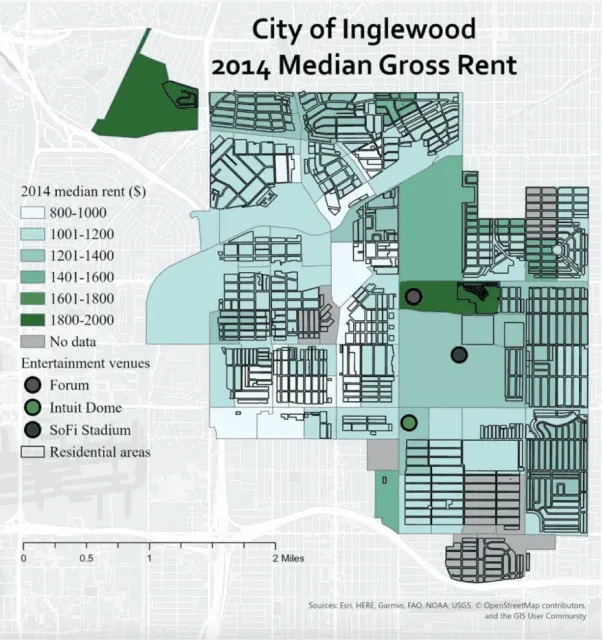

In the decade since the entertainment district was pitched, the city of 100,000 has lost more than 11,000 Black residents, while gaining residents of every other race. The white population in particular has jumped by 60%. Across LA County, the disappearance of Black residents isn’t unique to Inglewood, but it is double the county’s displacement rate.

Simultaneously, median household incomes around the district have climbed from $56,000 to $71,000 since the first shovels hit dirt for the Intuit Dome. In 2019, two-bedroom rents in an apartment complex next door to the arena jumped from $1,145 to $2,725.

“The issue with all this is: Who is it for?” Alexis Aceves, a member of the Lennox-Inglewood Tenants Union, told Capital B before the dome was built. “All of these changes and investments are supposedly ‘revitalizing’ the city, but it has just ended up being worse for all of us here.”

A $100 million climate deal, and greenwashing accusations

In 2019, as the Intuit Dome’s permits were being fast-tracked, Inglewood Mayor James Butts proudly boasted that without his work to bring the stadiums to the community, the city would remain “devoid of hope with no aspiration for the future.”

The stadiums, which are the most expensive ever built for their respective sports, were pitched as a catalyst for rebirth. Still, few communities bear the cost of “green” and entertainment spectacles like Inglewood, where residents have long accused elected officials, arena owners, and the Olympic committee of “greenwashing.”

Greenwashing is when companies exaggerate or misrepresent their environmental credentials or the environmental benefits of their products, often through the use of misleading claims or marketing tactics. Carbon offsets often find themselves at the center of these allegations.

Los Angeles Clippers owner Steve Ballmer attends the Intuit Dome steel topping celebration in 2023. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Clippers)

Offsets are when companies that are major environmental polluters pay middlemen to plant trees in faraway forests to make up for their local emissions. The trees are planted to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but they are only effective if the trees survive to maturity and are not cut down or destroyed.

As part of the Intuit Dome’s climate plan, the Clippers struck a headline-grabbing deal with Aspiration, agreeing to pay the fintech firm and its celebrity backers more than $100 million over two decades to supply carbon credits and feature the Aspiration logo on jerseys and in the arena.

But beneath these promises, federal investigators discovered a web of misconduct. Aspiration was accused of misrepresenting the quality of its carbon offsets, selling credits from projects that never materialized or failed to provide verified climate benefits. Lawsuits claimed that tens of millions of dollars that Aspiration supposedly dedicated to reforestation were spent on projects with no climate impact or missing documentation.

Even before the fraud was made public, one community group wrote that the partnership with Aspiration in Inglewood exemplified the “art of bamboozle.”

Meanwhile, a separate $28 million “endorsement” with star Clippers forward Kawhi Leonard is now under NBA scrutiny for the possibility that offset funding was used as a loophole to pay players extra, skirting the league’s strict salary cap rules.

By 2025, Aspiration collapsed into bankruptcy as lawsuits and federal probes mounted. With the company’s promises and funds evaporating, neither the trees nor the promised climate relief ever appeared, leaving Inglewood with rising pollution, residents said.

Kawhi Leonard at the Intuit Dome steel topping celebration in 2023. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Clippers)

Aspiration’s co-founder, Joe Sanberg, was a major Democratic donor, contributing over $1 million to Democratic candidates, including Governor Newsom, in the past decade, according to OpenSecrets donation records.

Even before the arenas were constructed, the community living directly around them was found to be exposed to more environmental burdens than 96% of the state. And nearly 9 out of 10 residents viewed “traffic-related air pollution from cars” as a major problem.

The partnership did in fact lead to at least some trees being planted in Inglewood, according to the city. On paper, a thousand saplings might erase 10 to 15 metric tons of carbon dioxide a year, but just one Clippers home game can pump more than 100 metric tons of CO₂ into the air, simply from the sea of cars that flood Inglewood’s streets.

When the projects were first announced, one community group accused the city of partaking in “greenwashing.” In 2023, when the Los Angeles Clippers planted trees, the group called it “the art of bamboozle.” (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Clippers)

Fushcia-Ann Hoover, a researcher focused on green infrastructure planning in cities, sees the pattern all too clearly. These projects, she said, “bring amenities and investment but leave the people behind — especially those already burdened by pollution and displacement.”

Hoover warned that green infrastructure investments often spark “green gentrification,” attracting wealthier newcomers and driving displacement while failing to protect existing residents. The surge of new amenities and transit lines brings rising rents and housing insecurity, rather than relief or prosperity, for the community intended to benefit.

“With most offset programs, there isn’t a requirement that the benefit stays local,” she explained. “The challenge comes not just in whether companies carry through what they say they’re doing, but in the fact that you are damaging a community that isn’t going to receive the benefit of those credits.”

In a statement released in September, the Clippers said the Ballmer family is “focused on sustainability, which is why Intuit Dome was designed to be a carbon-neutral building from its inception. Our development agreements for the arena included mandates to buy carbon credits.”

“Some of those commitments were built into the sponsorship deal with Aspiration — totally separate of the investment in the company — and we made payments to Aspiration until the company was unable to fulfill their responsibilities,” the statement went on. “The effort reflects Steve wanting to set a positive example and raise awareness of the growing and important role of voluntary carbon markets. Unfortunately he was duped on the investment and some parts of this agreement, as were many other investors and employees.”

Regardless of what the arena owners and city officials intended, what residents have experienced in Inglewood “is a fundamental justice failure,” Hoover said.

According to the state’s health department, since 2019, 2 out of 3 people that die in the neighborhood directly around the stadiums are Black, but Black people now only make up 1 out of 3 people living in the ZIP code. At the same time, asthma-related hospitalizations in that community have risen to roughly twice the California average.

Despite repeated requests, the LA Clippers, the city of Inglewood, and Newsom’s office did not respond to questions regarding their efforts to address worsening air pollution and rising health burdens in stadium-adjacent neighborhoods, the rapid displacement of Black residents and increases in local housing costs, the credibility of “green” claims after their offset partner faced federal fraud charges, and what steps are being taken to guarantee transparency and community involvement going forward.

“The majority of Inglewood residents are not utilizing that ‘entertainment district,’ and unfortunately because of it, the average Black family will no longer be able to buy a house in Inglewood,” said Yolanda Davis, a lifelong Inglewood resident. Davis fears her 23-year-old daughter won’t be able to grow old in her community. Already, Davis was displaced once since the stadiums were built after a corporate housing company bought her former apartment complex and raised the rent.

“The billionaires already had their money when they came, they don’t need or deserve Inglewood’s money,” Davis said. “They don’t care about us; that is supposed to be our elected officials’ jobs, but they don’t seem to care, either.”

Since 2020, residents across the city have staged protests outside new developments meant to attract new, wealthier residents. (Courtesy of Kemal Cilengir/Lennox-Inglewood Tenants Union and NOlympicsLA)

The future of Inglewood’s Black community

Mayor Butts, who has received nearly half a million dollars in campaign contributions from Ballmer, has frequently emphasized the transformative significance of the Intuit Dome, describing it as the latest and greatest achievement in Inglewood’s economic renaissance. With the city requiring that one-third of workers come from Inglewood, it has brought in millions in wages.

These days, drives that once took Davis 20 minutes, take as long as an hour. “I can make it work, but what about my neighbor who’s 82, my neighbor who’s disabled, and my neighbor who is on the bus?” she said.

Residents said perhaps most quietly devastating is the change in how people relate to their home: a lingering sense that the city they’ve invested in for generations is now designed with others in mind.

Steven Fisher, a 56-year-old lifelong resident, said it has even changed social norms. Recently, a neighborhood block party was disrupted by new residents who had “fears and concerns” about the party leading to violence.

Inglewood’s Black community had to fight for generations through racist home loan systems and the aftermath of the 1992 LA riots, which makes the community disruption even more devastating, Fisher said. “When you have a people who had to fight so hard to establish a community, then you see when that community finally gains opportunity and it is not for you, that is exceptionally hard and hurtful.”

This is seen deeply in the transformation of Inglewood’s public schools since the development of SoFi Stadium and the Intuit Dome.

School closures have accelerated: in the past year, six schools have been shut down, all in neighborhoods where Black and brown families have historically lived. Officials attribute them to declining enrollment and deteriorating infrastructure, such as a gas line rupture that left Morningside High without heat for a month. But some residents say it shows a lack of investment and support.

Community activists warn that these closures contribute to gentrification, with land being converted into “housing that nobody in our community can even afford.” Newer, wealthier residents largely avoid sending their children to Inglewood’s public schools. Instead, these families tend to enroll their children in private schools or charter schools outside the city, contributing to a declining school population.

A nationwide study in 2022 found that school closures actively increase gentrification, and the impacts have been most profound in predominantly Black neighborhoods. The findings revealed that shutting down public schools undermined long-standing community anchors, opening the door for wealthier newcomers while accelerating property turnover and rising rents.

That same year, a study comparing 472 stadiums found that areas near stadiums across the U.S. experience higher rates of displacement among Black and Latino residents after they’re built.

Inglewood’s future remains uncertain, Dixon said, not for lack of hope, but because the direct costs of transformation have fallen squarely on those who built the community in the first place.

“If we don’t have public schools, we won’t have Black children,” Dixon said, “and without Black children, we no longer have Inglewood. That just leaves billionaires and their ‘sports and entertainment’ district.”

Since the 2016-2017 school year, when SoFi Stadium began construction, Inglewood’s public school enrollment has dropped from 9,000 to 7,000. (Courtesy of Fre’Drisha Dixon)

Read More:

From Watts to D.C.: How 500 Black Neighborhoods Vanished in 45 Years

The post In LA, Olympic Dreams Lead to Nightmares for a Historic Black Community appeared first on Capital B News.