Justin Clapp’s introspection about his own impact on mountain lions is partly what sparked a scientific examination of how the big cats respond to being bumped off carcasses mid-feast.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s large carnivore biologist, along with colleagues and fellow researchers, repeatedly displaced feeding cats — 26 individual research animals — while trying to answer questions about how, or if, lions selectively prey upon vulnerable, chronic wasting disease-stricken ungulates in the Laramie Mountains.

“From an ethical standpoint, when we collar animals, we are asking a lot of them,” said Clapp, who’s also a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wyoming. “We don’t take that lightly. We recognized that, if we were going to get to kill sites quick enough to get a CWD sample, then we were probably going to be at a lot of these sites while those animals are still feeding.”

Those inevitable displacements could have cascading effects. Perhaps lions, once bumped off carcasses, moved on to kill their next meal quicker, which in turn could theoretically impact prey species like elk and mule deer.

But Wyoming researchers tracking 16 toms and 10 adult females from 2019 to 2023 discovered just the opposite. Clapp, along with Wyoming Game and Fish’s Justin Binfet, Idaho Fish and Game’s Cade Bowlin and University of Wyoming ecologist Joe Holbrook, recently published their findings in a peer-reviewed study. Its title hints at the results: “Large carnivore feeding is resilient to human disturbance.”

“We really did not see carcass abandonment,” Holbrook said. “And even more interesting, as a lion experienced [more] encounters with humans, the probability of them returning back to the carcass increased. So there was some evidence of habituation and learning.”

The treed mountain lion pictured is one of 26 cats that were tracked by Wyoming researchers from 2019 to 2023 in the Laramie Mountain area. (Justin Binfet/Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

The treed mountain lion pictured is one of 26 cats that were tracked by Wyoming researchers from 2019 to 2023 in the Laramie Mountain area. (Justin Binfet/Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

The kill rates of feeding mountain lions actually decreased, the researchers found, because the displacements extended their time at any one carcass.

By and large, the findings buck conventional scientific thinking. Humans have long been regarded as “superpredators,” and people, primarily houndsmen, pose a lethal risk to the cats in a state where they’re heavily hunted. And so it wouldn’t have been especially surprising if lions were easily disturbed and abandoned carcasses when confronted by teams of biologists.

Mountain lions, to be clear, did move off of their venison meals.

“We did not encounter one instance of cats defending the carcass,” Clapp said. The only behavior that could be categorized as aggression was encountered when the biologists went to examine a cluster of GPS points that was suspected to be a carcass, but instead ended up being a den full of kittens.

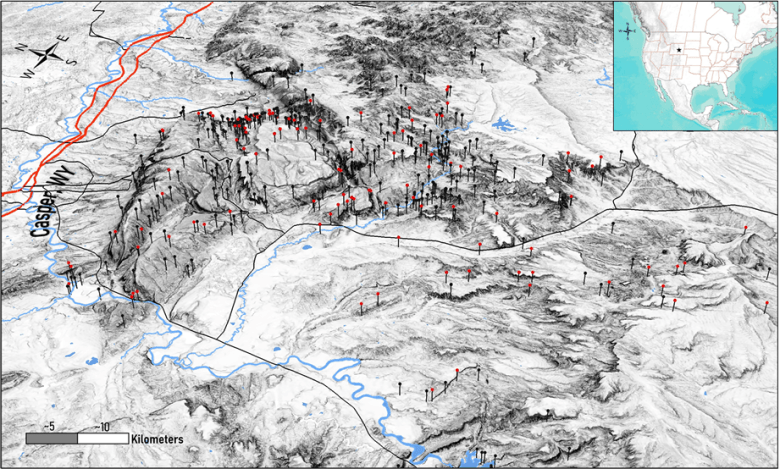

This study area map shows field investigations of mountain lion feeding sites that resulted in human disturbance (red) and undisturbed feeding events (black) in central Wyoming between 2019−2023. (Proc. R. Soc.)

This study area map shows field investigations of mountain lion feeding sites that resulted in human disturbance (red) and undisturbed feeding events (black) in central Wyoming between 2019−2023. (Proc. R. Soc.)

Over the course of the study, biologists and technicians identified feeding activity at 745 sites. Clapp, Holbrook and the other researchers parsed the data in a way that identified 106 instances of human disturbance.

Of those, 25% of the time there were “direct encounters,” when the scientists either saw or heard the cats. The remainder were identified via GPS data and were labeled “proximity encounters.”

Disturbed cats did flee and leave the area more than 70% of the time, the research showed. But 72% of the time, those cats returned. In total, lions either never left the immediate area or returned to their kill site after a disturbance 80% of the time. On average, they moved off by two-thirds of a mile, and they were gone for about 13 hours.

The data amassed in the Laramie Mountains also showed just how quickly disturbed cats smartened up. Every time they got bumped off a carcass, there was a corresponding 22% increase in the odds that the mountain lion returned.

Clapp emphasized that the study results are not intended to downplay the effect that human activity can have on mountain lions, or any species. But the findings exemplify the impressive resilience and intelligence of apex predator species like mountain lions, he said.

“We need to make sure that we’re giving them credit for their adaptability and for the way that they can continue to persist, reoccupy, expand, despite the things that humans do,” Clapp said. “While I’m not saying that human disruption is good for any type of wildlife, we need to make sure that we’re acknowledging the fact that these animals are pretty incredible and they’re very smart.”