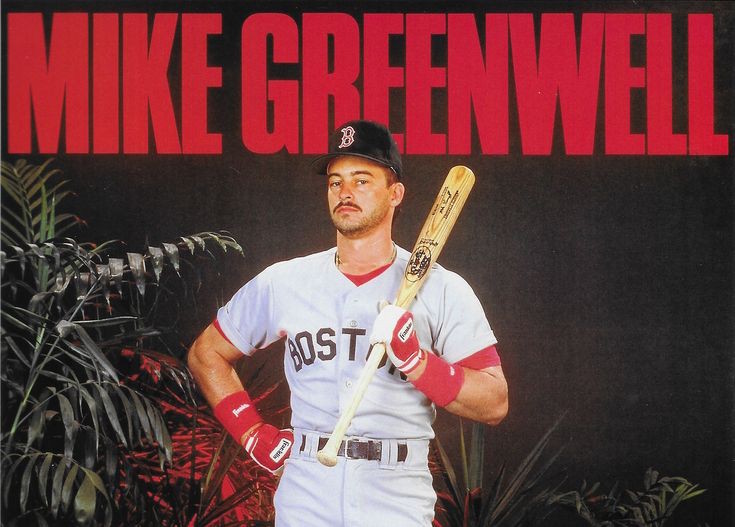

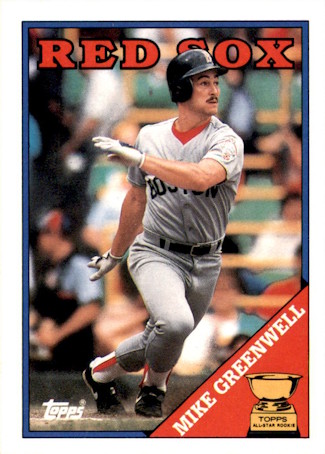

If you lived in the era of junk wax baseball cards and “This Week in Baseball” shows on Saturday morning, opening a pack of 1988 Topps and seeing a Mike Greenwell card, with his All-Star Rookie trophy in the corner, was a great pull. At the time, Greenwell was putting together an MVP-like season after being one of the AL’s top rookies the previous year. He was a star in the making, and it came as a shock that injuries and dissatisfaction with Boston Red Sox contract offers ended his MLB career at age 33. Greenwell still had an excellent 12-year career with the Red Sox from 1985 to 1996, retiring with a lifetime .303 batting average. His post-baseball career included auto racing, theme park ownership, and a stint as the Lee County commissioner in Florida. He was appointed to the role by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in July 2022, and he held the position right up to his death on October 10. He had been previously diagnosed with medullary thyroid cancer, and the illness had prevented him from attending public meetings recently. Greenwell was 62 years old.

Speaking of that 1988 Topps card, the guys at the Topps 1988 Podcast had a great episode on Mike Greenwell in 2023. It’s a fun listen that first made me aware that, behind the steady hitting and impeccable moustache, Greenwell was a heck of a character.

14-year-old Mike Greenwell as a high school ballplayer. Source: News-Press (Fort Myers, FL), May 9, 1990.

14-year-old Mike Greenwell as a high school ballplayer. Source: News-Press (Fort Myers, FL), May 9, 1990.

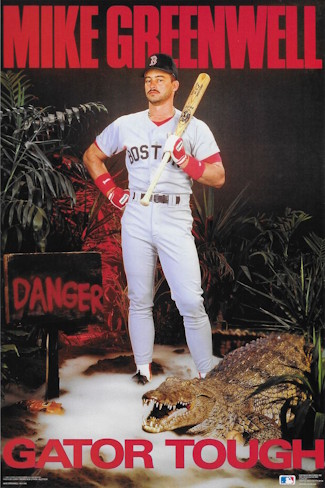

Michael Lewis Greenwell was born in Louisville on July 18, 1963, but he spent most of his life in Florida. In fact, when he entered pro baseball, he had the nickname of “Gator” because he wrestled alligators, which is about as Florida as it gets. Greenwell started attracting attention for his play as a sophomore third baseman for North Fort Myers High School. The team jumped out to a 14-2 record to start the 1980 season, and Greenwell batted .449 and reached base at a .627 clip. He struck out one time in his first 49 at-bats. “He has one of the most natural swings I’ve ever seen,” said his coach, Ted Ferriera. Greenwell remained one of the team’s best hitters throughout high school, but he didn’t always have the best luck. Fort Myers dropped a playoff game to Tampa Catholic in 1981, and it didn’t help that Greenwell got ejected — from a high school playoff game! — for allegedly kicking dirt on an umpire when he was called out trying to steal second. “Aw, I guess I came in there and got dirt on him when I slid,” he said. “I got up and looked at him and he said, ‘You’re out of the game.” He didn’t give me a chance to say anything bad.”

Greenwell capped off his high school career by being named to the Fort Myers News-Press All-Area Team in 1982. Through his 3 seasons on the varsity squad, he batted .459 with 106 hits in 231 at-bats, 9 home runs, 78 stolen bases, and 12 strikeouts. Yes, 12 strikeouts in 3 seasons. That June, he was taken by the Boston Red Sox in the Third Round of the 1982 Amateur Draft. Greenwell started his pro career with the Elmira Pioneers of the New York-Penn League, and the 18-year-old managed a .269 batting average, with 6 home runs and 10 doubles. He got off to a great start in 1983 but was sidelined for several months with torn cartilage in his knee. Greenwell didn’t put together his first great season until 1984, which was his third season at Class-A. He batted .306 for Winston-Salem with 16 home runs and 84 RBIs. After struggling at third base to start the year, he moved to the outfield for good. It was just as well, because the Red Sox third baseman, Wade Boggs, was in the process of locking down third base for the next decade or so.

The Red Sox moved Greenwell to Triple-A Pawtucket in 1985, and he made the International League All-Star Team with a .256 average and 13 home runs. He was promoted to the majors in September to spell the ailing Jim Rice and Tony Armas. Greenwell debuted as a pinch-runner for Rice late in the game on September 5. He was given a start in left field on September 13, and he was 0-for-3 with 2 strikeouts against Milwaukee. Greenwell didn’t get a hit until his eighth major-league game on September 25. He came to bat in the 13th inning of a 2-2 game between Boston and Toronto. Bill Buckner had led off the inning with a double, and Greenwell belted a 2-run homer off John Cerutti. His second major-league hit came the very next day, and it was another 2-run homer off Blue Jays pitcher Doyle Alexander. His third hit didn’t come until October 1, and Greenwell smashed a long solo homer off Baltimore’s Eric Bell. Greenwell was the first player to have his first 3 major-league hits all be home runs. He ended his brief trip to the majors with a .323/.382/.742 slash line, with 4 home runs in 17 games. “When I first went up I had no idea how much I’d play,” Greenwell said in October. “I heard Rice and Armas were injured, so I knew I would get some time, maybe 5 or 6 at-bats. This was beyond my expectations though.”

Greenwell’s excellent September/October in 1985 didn’t guarantee him a roster spot in 1986, and he began the season in Pawtucket before returning to the Red Sox in July. Manager John McNamara used Greenwell mainly as a pinch-hitter and occasional substitute for the team’s veteran outfielders. He batted .314 in 31 games and 35 at-bats. Boston won 95 games and finished first in the AL East. The team moved past the California Angels in the AL Championship Series before losing to the New York Mets in a rather infamous World Series. McNamara relied heavily on his veteran players, so Greenwell did nothing in the postseason but pinch-hit. He had a hit in 2 at-bats in the ALCS and was 0-for-3 with a walk and 2 strikeouts in the World Series. He started 1987 in the majors but still had the same pinch-hitting role… for a little while. Greenwell was the starting left fielder in back-to-back games in Seattle on April 29 and 30 while filling in for an injured Rice, and he homered in both of them. He was added to an incredibly packed outfield/designated hitter crew, which contained Rice, Don Baylor, Ellis Burks, Todd Benzinger, Dave Henderson, and (later in the season) Sam Horn. Players were shuffled around regularly, and Greenwell kept shifting from left field to right field to DH. He was even an emergency catcher in a game where McNamara pinch-hit for the only two healthy catchers on his roster and entered the 10th inning of a July 18 game against Oakland with nobody behind the plate. Greenwell was shifted from DH to catcher for an inning. “I was scared. I was nervous,” he said, adding that his previous catching experience came during a high school game. “I believe in doing anything that’s needed to help us win. So I got out there, and it was awful. I thought the inning would never end.” That’s not an exaggeration. The top of the 10th inning lasted more than a half-hour, as the A’s pounded 7 runs off three different Red Sox relievers. Terry Steinbach started the inning with a ground-rule double, and Alfredo Griffin deliberately bunted near home plate so that Greenwell had to make the play. He threw the ball over first base, letting Steinbach score. Most of the damage in the inning was due to ineffective Boston pitching, but Oakland’s Luis Polonia took advantage of the situation by stealing second and third on Greenwell after he walked. Oddly, Greenwell recorded 3 potouts because all of Oakland’s outs came via the strikeout. He never had to catch again, and he should never have been put in that position in the first place.

Source: St. Cloud Times, September 2, 1990.

Source: St. Cloud Times, September 2, 1990.

Throughout all the position changes and role changes, Greenwell never stopped hitting. His batting average dipped below .300 for just a handful of games, and he batted .359 in the month of August to prove he deserved more playing time. “I don’t want to be a who who maybe spends five years in the major leagues being a backup player. A guy like, maybe, Reid Nichols — a guy that just never really maybe got the opportunity,” he said in June. “I want to be a guy who has a role right now as a backup player, is willing to be the best backup player he can… but who also wants that chance to be an everyday player.” By the end of the year, Greenwell had slashed .328/.386/.570 with 19 home runs, 89 RBIs and 31 doubles. He finished fourth in the Rookie of the Year vote (Mark McGwire and his 49 homers won the award) and left no doubt that he was a starter. And the next year, he showed that he was a star.

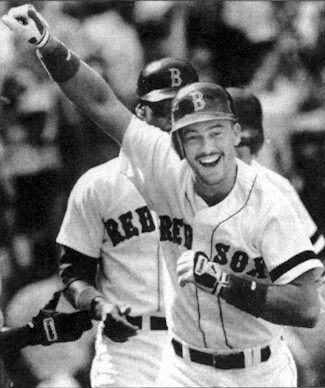

First, the numbers. Greenwell, in 1988, had a slash line of .325/.416/.570 in 158 games. He had 39 doubles, 8 triples and 22 home runs among his 192 hits. He scored 86 times and drove in 119 runs, and he drew 87 walks while striking out just 38 times in 590 at-bats. He was a Top Five hitter in almost every offensive category and led the AL with 18 intentional walks. After a slow period in May and early June that saw him bat “only” .278, Greenwell hit .456 during a 19-game hitting streak. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody this hot,” commented Benzinger. Defensively, Greenwell established himself as an excellent left fielder. Previously, he was only a mediocre fielder as he bounced between corner outfield spots. But in 1988, he had a .987 fielding percentage and, per Baseball Reference, saved about 14 runs, which topped all MLB left fielders. He was named to the AL All-Star team and was 0-for-1 after entering the game in the sixth inning. From a Boston standpoint, Greenwell did something special when he moved Rice from LF to DH. Left field was a special position for the Sox, having been transferred seamlessly from Ted Williams to Carl Yastrzemski to Rice — 3 Hall of Famers. Now, the role went to Greenwell. Greenwell understood what being a Red Sox left fielder meant, and he was ready for the responsibility. “I’ve learned a lot in the last two weeks,” he said after his hitting streak ended. “I’ve learned that I can help to be a leader off the field and be a leader in the field with my bat. When I learned that, it kind of possessed me to go out and bring everything I had into it. Now I’m getting hot, and I think everybody’s getting into it.”

Greenwell’s leadership helped spur the Red Sox to a late-season surge (which happened after McNamara was fired and replaced with Joe Morgan), and the team took over first place in the AL East in September. Boston won 89 games to finish ahead of Detroit by 1 game and move into the ALCS. Boston was swept by Oakland and the Bash Brothers of McGwire and Jose Canseco, and Greenwell batted just .214 in the four losses with a solo homer off Bob Welch. Greenwell’s focus, understandably, may not have been solely on baseball. His father suffered a heart attack late in the season, and his wife was due to give birth to their first child during the playoffs. Both his father, Leonard, and wife, Tracy, asked him to stay with the team, but he later acknowledged how mentally exhausting the final weeks of the season were. Greenwell was named a Silver Slugger after the season, and he finished second in the MVP vote to Canseco. Canseco led baseball with 42 homers and 124 RBIs, and he became the first player to reach the 40-40 club by stealing 40 bases. That accomplishment swayed voters to the point that Canseco finished first on all 28 MVP ballots. But that vote overshadows Greenwell’s spectacular season, not to mention great performances by Kirby Puckett and Wade Boggs. The Sox, with Greenwell and Boggs leading the offense and a pitching staff anchored by Roger Clemens, looked poised to contend for years.

It was an extraordinary year, and Greenwell’s 1989, while still All-Star level, was a drop. Morgan counted on his young outfielders of Greenwell and Burks to deliver more power, and both players added muscle over the offseason. Greenwell also had the mantle of being the Red Sox Left Fielder. “It’s nice to be compared to great players, but when you start doing that, you put pressure on yourself that you don’t have to,” he said. “I just want Mike Greenwell to be Mike Greenwell — the best he can be.” The left fielder started the season with 3 home runs in his first 3 games, but the power never really materialized. He still slashed .308/.370/.443, had a 21-game hitting streak and drove in 95 runs, but his home run total dipped to 14. He had just 2 long balls after August 1. Greenwell was named to his second All-Star Game, but he was a late-inning defensive replacement for the sport’s new phenom, Bo Jackson. After the season, Greenwell found himself the subject of trade rumors to the Atlanta Braves, though Red Sox manager Lou Gorman dismissed the reports, “Unless somebody overwhelms us.” Greenwell was shocked and hurt by the reports, especially after three straight .300+ seasons, but he admitted that playing in Atlanta would have a lot of appeal. The trade rumors didn’t subside when Greenwell started off 1990 in an awful slump. He spent April and May hitting in the .220s, and Morgan even pinch-hit for him occasionally in clutch situations. Greenwell picked up the pace as soon as June came around, and he ended the year with a .297 average, 14 homers and 73 RBIs. He hit a rare inside-the-park grand slam home run as part of a 15-1 whipping of the New York Yankees on September 1. It was the second inside-the-parker of Greenwell’s career, and they both came against the same pitcher, Greg Cadaret. But the early slump, paired with an 0-for-14 performance as the Red Sox were swept by Oakland in the ALCS, brought out the critics and boobirds. They said he wasn’t a clutch hitter or a good fielder. As the negativity rose, Greenwell thought more about that rumored trade to Atlanta. “They have a lot of talented players,” he said. “I think maybe there’s just a couple of players away. Maybe a left-handed outfielder [which Greenwell was].”

The talk of trades ended in the 1990-91 offseason, when Greenwell and the Red Sox agreed on a 4-year contract. He hit an even .300 in 1991 and drove in 83 runs, despite just homering 9 times. But most of Greenwell’s headlines didn’t have anything to do with his play. On June 1, a photo of Greenwell driving around Seekonk Speedway in his stock car ran in the Boston Herald, raising questions about whether he had violated the terms of his new contract. GM Gorman put an end to that hobby, for the time being. Later that month, Greenwell and second baseman Luis Alicea got into a shoving match in the Red Sox dugout and had to be separated. One of the witnesses to the fight was rookie Mo Vaughn, who had been promoted to the majors just days before. That August, Vaughn and Greenwell got into their own fight, this time at a batting cage in Anaheim. The brawl began when Greenwell tried to set a limit on the swings Vaughn would take (something a veteran might do with a rookie), and Vaughn got in his face. Greenwell was initially blamed, and racism was suggested as a cause. After the incident didn’t die down after a few days, Greenwell gave his side of the story. The rookie had privately apologized to Greenwell, and the veteran said he held no hard feelings against Vaughn. “But I do know this. I would never have done what he did to me to Jim Rice, or Dwight Evans, or Don Baylor, because I respected them, not only as baseball players, but as men and veterans. I think Mo made a mistake there,” he said. Because he felt he had been unfairly blamed for the fight, Greenwell vowed to stop talking to the press.

Greenwell kept up his boycott of the press until spring training in 1992. He sounded off on Morgan, who had been replaced by Butch Hobson as manager, for failing to back him up in the wake of the Vaughn brawl. He also addressed the way his off-field incidents made him unpopular among some fans. “For people to say I’m a liar, a phony, a troublemaker when they have no idea what type of person I am… I’ve gotten myself in trouble because I tell the truth,” he said. Greenwell didn’t have much of a chance to win over the fans that year. He had aching knees that affected his offense, and he suffered a season-ending elbow injury in late June. In 49 games, Greenwell batted .233. Greenwell’s style of play — all-out hustle and diving into first base if necessary — inevitably led to injuries that took their toll on the rest of his playing career. The season-ending surgeries on his right elbow and right knee kept Greenwell away from baseball, but it did let him focus on some non-baseball interests. He owned a stock car racing team, driven by Mike Hovis. He also ran an amusement park in Fort Myers called Mike Greenwell’s Bat-a-Ball and Family Fun Park.

After rehabbing his injured body parts, Greenwell bounced back in 1993 with a typically good season. He started off hot by picking up a triple and 3 RBIs on Opening Day, accounting for all the runs in a 3-1 victory over Kansas City. There were one or two dry spells during the season where he didn’t hit well, but it was a remarkably consistent year after his injury-plagued 1992. His surgically repaired joints worked, and the only time he went on the disabled list was due to a strained lower rib cage. He slashed .315/.379/.480 with 13 home runs and 38 doubles, and he drove in 72 runs. Off the field, a roster shake-up had left him and Clemens as the only players left from the 1986 World Series, and he took to his role of clubhouse leader. As “The Mayor,” Greenwell even closed his family fun park for a day in spring training so Red Sox players and their families could have the park to themselves. “Obviously, there’s other guys with more big-league experience on this team,” he said. “But I know the city, I know the media. I thought maybe I could loosen things up, get everyone to have a little fun. So far it’s worked. Everyone is upbeat.” Boston and its new roster finished 2 games under .500, for a fifth-place finish in the AL East. Clemens had an off year, and the team’s offense didn’t have much power beyond Vaughn. But after several years of stormy relationships with the fans and local media, Greenwell was happy and even cordial to the press.

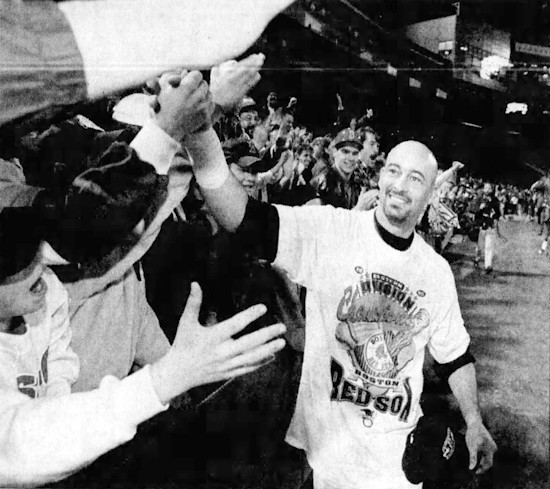

Greenwell’s four-year contract was due to expire at the end of 1994, and he made no secret of his desire to retire with the Red Sox. He and agent Joe Sroba sought a 4-year extension that paid him on par with the likes of Will Clark and Kirby Puckett ($4 million). Boston countered with a 2-year deal along the lines of Brady Anderson or Ellis Burks ($3 million). The gap of nearly $10 million proved too much to resolve. “I feel like I’m being punished for being open enough to say I want to stay here. I’m really shocked, to be honest with you,” Greenwell said after contract talks with new general manager Dan Duquette broke down in April 1994. “Loyalty is important to me. I’ve shown it, and somewhere along the line they have to show it back.” The ’94 Red Sox finished in fourth place for the strike-shortened year, and Greenwell hit 11 home runs in 95 games but batted just .269. He ultimately signed a 2-year contract for $7.3 million, and when the players and owners had settled their differences, he was one of the first players to arrive at training camp to smooth over any issues between the Sox regulars and the replacement players. “We have to be grown-up people and understand that these guys were put in a tough spot and they were trying to do the best thing for their own situation,” he explained. Greenwell also tried to improve relations between the fans and players and was a big part of Fanfest, a Boston event that drew about 30,000 fans. On the field, he fell just shy of another .300 season at .297, and he probably would have reached the mark had he not missed a month of the season after injuring his ribs in a collision with center fielder Lee Tinsley. Boston’s upgraded offense had big years from Vaughn, John Valentin and Jose Canseco, and the pitching staff got 16 wins from Tim Wakefield and 15 from Erik Hanson. The rebuilt team took first in the AL East with 86 wins, but it was again swept out of the playoffs, losing 3 straight games to Cleveland in the AL Division Series. Greenwell had 3 singles in 15 at-bats, and Canseco and Vaughn both went hitless.

Source: News-Press, June 25, 2006.

Source: News-Press, June 25, 2006.

The year of 1996 was a turning point for the Red Sox franchise. Veterans Greenwell and Clemens were in the final year of their contracts and were anxious to stay with the team for the rest of their careers. Team management did not reciprocate those feelings. “Baseball has enjoyed what the other sports haven’t been able to do — keep a player for his entire career,” Greenwell said in the offseason. “Maybe the new attitude in baseball is destroying that now. Nothing has meant more to me than being the left fielder in Boston for the past 10 years. Knowing there have been just 3 other players out there for the past 60 years is special.” Greenwell’s season was marred by a sore back and a broken ring finger, which kept him out of the lineup for two-and-a-half months. He was as steady as ever when he could play, batting .295. He had the game of his career on September 2, 1996, in Seattle. Greenwell drove in all 9 runs for the Red Sox as Boston won 9-8 in 10 innings. He hit a 2-run homer, a grand slam, a 2-run double and a tenth-inning single that put the team ahead for good. He set a record for the highest number of RBIs that accounted for a team’s total offensive output in a game. Several players previously had driven in all 8 runs in a game. “It was a storybook night. I feel like I still have something to give to this club,” Greenwell said. Boston did not agree. Duquette wouldn’t meet with him about another contract extension. Shortly before the season ended, Greenwell announced that he would not return to the Red Sox in 1997 and cleared out his locker. Boston’s second-to-last game of the season was a 4-2 loss to the Yankees in Fenway Park on September 28. Greenwell was 0-for-4 with a run-scoring groundout, after which he was taken out of the game as the fans cheered. Clemens took the loss. It was the final Red Sox game for both players, and the final one of Greenwell’s career.

In 12 seasons, Greenwell had a slash line of .303/.368/.463, and his 1,400 hits included 275 doubles, 38 triples and 130 home runs. He drove in 726 runs and scored 657 times. He drew 460 bases on balls while striking out just 364 times — an average of 30 times per season — and he stole 80 bases. He had a .982 fielding percentage in left field, and he led the AL in left field assists 3 times. Baseball Reference credits him with 25.8 Wins Above Replacement, and he had a career .831 OPS and a 121 OPS+. When he left Boston, he was in the franchise’s Top 10 for most offensive categories, though he has been surpassed by more recent players. He was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2008.

Greenwell didn’t technically retire after the 1996 season; he just said he was going back home to Florida. He signed a 2-year contract with the Hanshin Tigers in Japan, but his career overseas lasted for just 7 games, in which he batted .231. He had 5 RBIs, and two of them won ballgames. He injured his back in spring training, missed the start of the season, and then rejoined the team in May. Then Greenwell fouled a ball off his foot, and while Hanshin team doctors diagnosed it as a bruise, Greenwell later learned it was broken. Rather than miss a month or more with another injury, he elected to retire instead. “I wanted to leave the game with honor and not just try to play for money,” he said at his retirement news conference. “He hasn’t lost his talent, but his body just isn’t able to recover like it used to. He plays hard, and he’s going to get hurt,” his wife Tracy told the News-Press of Fort Myers. He and Tracy had two sons, Bo and Garrett, and the family had planned to join Greenwell in Japan once school was out. Bo later spent 8 seasons in the minor leagues as an outfielder in the Cleveland and Boston organizations, and Garrett played college ball at Oral Roberts University.

In retirement, Greenwell stayed in Fort Myers with his business interests. He exited the amusement park industry when he sold Mike Greenwell’s Bat-a-Ball Family Fun Park in 2000 to get involved in real estate development. The park still exists and has been renamed Gator Mike’s in honor of its founder. Greenwell coached little league baseball and was ejected from a couple of games for arguing with the umpire, but he had no such issues as an assistant hitting coach with Riverdale High School, where Bo played ball. When the steroid scandal of the 2000s struck, Greenwell lobbied to be named the real MVP of the 1988 season, given that Canseco had admitted to steroid usage. “I was clean,” he said. “If they’re going to start putting asterisks on things, let’s put one by the MVP.”

Greenwell briefly returned to professional baseball when he became a batting coach in the Cincinnati Reds farm system. He joined the big league club as an interim coach in 2001 when Ken Griffey Sr. needed to take a leave of absence due to injuries. During his retirement, Greenwell also pursued his other sport — stock car racing — and made his NASCAR debut in 2006 with a Truck Series race in Mansfield, OH. He started 20th and finished 26th. He made just one more NASCAR appearance that year, but he raced until 2010. After years of working in the real estate business, Greenwell became an unlikely politician. He was appointed by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis as Lee County Commissioner in 2022, filling the seat of the late Frank Mann. Greenwell ran for election and won in November 2024 with about two-thirds of the popular vote. He announced his cancer diagnosis this past August.

Follow me on Instagram: @rip_mlb

Follow me on Facebook: ripbaseball

Follow me on Bluesky: @ripmlb

Follow me on Threads: @rip_mlb

Discover more from RIP Baseball

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.