Seeing is not believing when it comes to dark matter.

Scientists have blown stargazers’ collective minds after discovering a massive dark object in space that’s completely invisible to the naked eye, per an awe-inspiring study in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The enigmatic dark matter, which has yet to be named, reportedly has a mass that is a million times greater than the sun but does not emit light, Phys.org reported. This intergalactic blind spot reportedly resides over 10 billion light-years away, so we’re observing it when the Earth was only 6.5 billion years old — less than half of the planet’s current age.

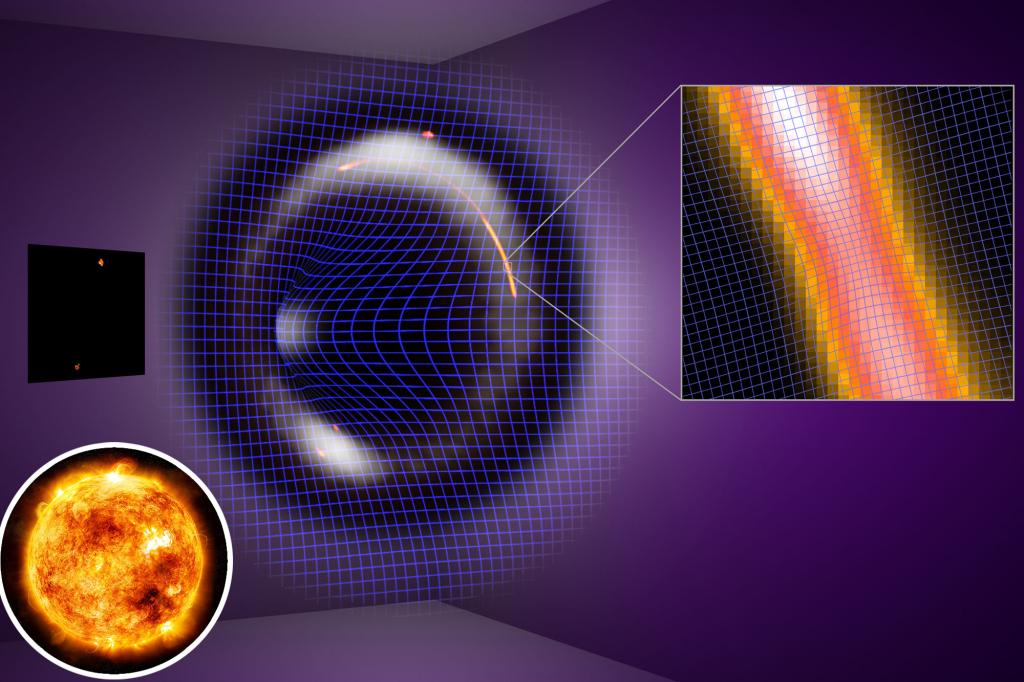

The dark matter object as seen by the team’s massive telescope. NSF/AUI/NSF NRAO/B. Saxton

Since the dark matter could not be seen, researchers had to observe it via gravitational lensing, in which the light of a more distant object is distorted and deflected by the gravity of said dark entity — like a celestial funhouse mirror.

“Hunting for dark objects that do not seem to emit any light is clearly challenging,” said lead author Devon Powell of the Max Planck Institute of Astrophysics in Garching, Germany. “Since we can’t see them directly, we instead use very distant galaxies as a backlight to look for their gravitational imprints.”

Despite dwarfing our solar star, this particular object was the lowest-mass object ever discovered using the gravitational lensing method — by a factor of 100.

Despite being a million times bigger than the sun (pictured), the object is the lowest-mass entity ever detected via gravitational lensing. Artsiom P – stock.adobe.com

To shine a proverbial light on said mysterious object, the team relied on a network of telescopes around the world, including the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia and the Very Long Baseline Array in Hilo, Hawaii.

They then correlated the resultant data to create an “Earth-sized super telescope,” as the researchers described it, with which they could capture the subtle signs of gravitational lensing and make it less of a cosmic shot in the dark.

They also had to develop advanced computational algorithms and even harnessed supercomputers to crunch the sprawling datasets.

A zoom showing the pinch in the gravitational arc. Keck/EVN/GBT/VLBA

Thankfully, their analysis paid dividends.

“From the first high-resolution image, we immediately observed a narrowing in the gravitational arc, which is the tell-tale sign that we were onto something,” said John McKean, of the University of Groningen of the Netherlands, who spearheaded the data collection. “Only another small clump of mass between us and the distant radio galaxy could cause this.”

Discovering clumps are significant because they expand our understanding of dark matter, material that is believed to exist in space but without visible light to prove it.

In fact, some studies have suggested that dark matter may even predate the Big Bang, the rapid inflation of our universe some 13.8 billion years ago.

“Finding dark matter clumps like this is a critical test of our understanding of how galaxies form,” said Dr. Powell. “The discovery fits beautifully with the number of dark objects we expected to find, but every new detection helps refine or challenge our theories.”

He added, “Having found one, the question now is whether we can find more and whether their number will still agree with the models.”