The apartment complex at 801 Alma St., which opened in 2014, is one of a just a handful of multi-family developments that have been built near the downtown Caltrain station in recent years. Embarcadero Media file photo by Veronica Weber.

The apartment complex at 801 Alma St., which opened in 2014, is one of a just a handful of multi-family developments that have been built near the downtown Caltrain station in recent years. Embarcadero Media file photo by Veronica Weber.

As recently as this year, a new five- or six-story building in the heart of downtown Palo Alto would not only be difficult to imagine and nearly impossible to build.

But Senate Bill 79, which received the governor’s signature on Friday, would fast-track a project that height or taller — as long as it falls within a half-mile radius of the Caltrain station.

The contentious legislation from San Francisco state Sen. Scott Wiener overrides local zoning to enable taller, denser housing near public transportation stops in eight urbanized counties throughout the state. It takes effect on July 1, 2026, but its passage last week has left some Palo Alto officials reeling.

“Senator Wiener basically took a pencil to our communities and drew circles around transit areas with very little appreciation of how much this would radically alter the character of communities,” Council member Pat Burt said..

The city previously wrote to state representatives in opposition to SB 79, arguing that it would override its existing plans for upzoning. Palo Alto also certified its Housing Element last year, a document that plans for more than 6,000 housing units as required by the state. The Housing Element took months of back and forth with the state Department of Housing and Community Development and concentrated most of those required units in south Palo Alto.

The city has upzoned along El Camino Real to accommodate the influx in new housing, but SB 79 is issuing a directive to do the same at the city’s three Caltrain stations.

“By mandating statewide development standards based solely on proximity to transit, the bill would override carefully developed zoning, general plans, and environmental considerations — ignoring local context, infrastructure capacity, and community-driven planning,” the city wrote in its letter.

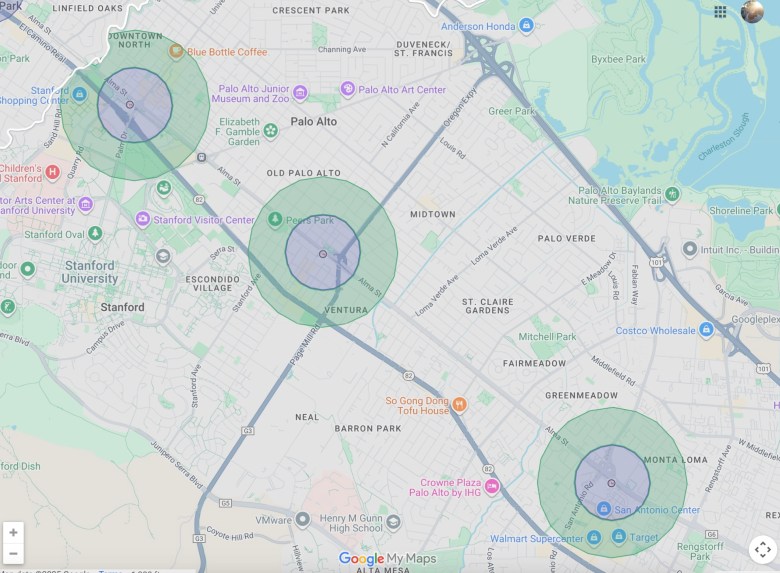

The bill allows developments of up to 75 feet tall and up to 120 dwelling units per acre in the ¼-mile radius around a major “Tier 1” transportation stop, which in Palo Alto’s case only applies to the three Caltrain stations that fall within its jurisdiction. The height and density lowers to 65 feet and 100 units per acre within ½-mile of the station.

Sites directly adjacent to a station, or within 200 feet, can go up to 95 feet and 160 units per acre, according to the bill.

SB 79 also directs agencies to measure based on the nearest pedestrian access point to the station, which could complicate the radii for cities and developers. Jurisdictional boundaries also present a challenge for mapping the upzoning. For example, Menlo Park is classified as a smaller city under SB 79, with a population just shy of 35,000 people. That means that the upzoning will only impact the area within ¼-mile radius around its Caltrain stations. Palo Alto, with its larger population, is subject to upzoning a ½-mile radius of its stations. Because of the differing standards, the radius around the downtown Palo Alto station is cut off at the city’s border with Menlo Park.

The map shows areas in Palo Alto where SB 79 would raise heights to 75 feet (in purple) and 65 feet (green). Map by Nolan Gay/Google maps

The map shows areas in Palo Alto where SB 79 would raise heights to 75 feet (in purple) and 65 feet (green). Map by Nolan Gay/Google maps

Metropolitan planning agencies are required to produce official maps of affected areas in the coming months.

The bill has particular implications for the city’s two area plans near the downtown and San Antonio Caltrain stations.

The Community Advisory Group for the Downtown Housing Plan has recently launched a series of meetings to explore different ways to encourage new housing in the area. But a community assessment report published in June found that the existing zoning and land use elements — such as a 50-foot height limit and ground-floor retail requirements — make it hard for projects to pencil out economically and “can be restrictive for mixed-use residential projects.”

Planning and Transportation Commission Chair Allen Aiken also serves on the advisory group for the Downtown Housing Plan. He said while city staff were looking at corridor-specific upzoning downtown, SB 79 instead acts as a blanket policy that essentially raises the floor for what the city can consider as changes to zoning in the area.

The same can be said for the San Antonio Road Area Plan, which envisions as many as 1,500 housing units near the eponymous Caltrain station.

The area near the California Avenue station could also feel the effects of SB 79, but the city has not prescribed the same housing action plan compared to Palo Alto’s other stations. Plenty of developers were already looking to the area for larger housing projects and took advantage of the fact that Palo Alto was delayed in certifying its Housing Element to bypass local zoning restrictions, otherwise known as builder’s remedy. One such example is the hotly debated proposal at 156 California Ave., which includes 17-story and 11-story buildings. This project, as well as another development at 414 California Ave., suggest that developer appetite is there for taller and denser housing in the area, despite the lack of a formal area plan from the city.

Redco Development has proposed a three-building, mixed-use development at 156 California Ave. in Palo Alto, with one 17-story tower. The zone-busting application is being submitted under a state provision known as “builder’s remedy.” Rendering by Studio Current/courtesy city of Palo Alto.

Redco Development has proposed a three-building, mixed-use development at 156 California Ave. in Palo Alto, with one 17-story tower. The zone-busting application is being submitted under a state provision known as “builder’s remedy.” Rendering by Studio Current/courtesy city of Palo Alto.

Some in Palo Alto are looking forward to the upzoning direction from the state. Palo Alto Forward is a local nonprofit dedicated to furthering housing and transportation development, and its new executive director Jeremy Levine described SB 79 as “the most impactful piece of housing legislation that has ever been passed in the state of California.”

“The city was already planning for more housing near its Caltrain stations,” Levine said. “This is just another tool in the toolbox to further that goal.”

Assemblymember Marc Berman, who voted in favor of the bill, said over email that it would “be irresponsible of me not to support efforts to build more desperately needed housing near mass transit in California.”

“While I do not think SB 79 is a perfect bill, we simply cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good when it comes to finding solutions to address our severe housing and affordability crisis in my district and throughout the Bay Area,” he added.

State Sen. Josh Becker initially voted to advance SB 79 through the legislative process but ultimately did not support the final version bill. Becker previously told this publication that the bill did not go far enough to differentiate between areas immediately next to transit stops and those somewhat further away.

Other than the existing builder’s remedy applications, 95-foot towers will not sprout by the Caltrain stations overnight, and cities can take advantage of a variety of exemptions until the next Housing Element cycle begins in 2031. That was after some heavy amendments in the legislative process to make SB 79 more palatable to critics who were worried about a state takeover of local zoning.

Cities like Palo Alto can choose to adopt a transit-oriented development alternative plan to relocate the density elsewhere, so long as the overall density and floor area is the same that it would have been under SB 79. Those plans would require certification by the state by July 1 of next year.

Burt described the alternative plan option as a “poison pill” because the turnaround may be too quick for cities to get approval, since the state can take up to 90 days to review the application after it has been submitted.

“It appears that to meet the July 1 deadline, we have to submit it by April 1, and hope that they would approve it,” he said. “Like the Housing Elements, there’s been this iterative process and in this case, it doesn’t seem to provide for any leeway.”

The city can also exempt a site from SB 79 if the city can prove there is no walking path of less than one mile from the site to the transit station.

It remains to be seen if Palo Alto will take SB 79 upzoning at face value or file an alternative plan with the state. But given the city’s ongoing rezoning plans near the Caltrain stations and historic opposition to the provisions of the bill, there is at least a strong possibility that the council will explore alternative paths to compliance.

The council will discuss SB 79 and its implication for the downtown planning processes at its Oct. 22 meeting. Whichever path the city chooses is almost certain to lead to taller buildings and more housing units than many in the city had anticipated just months ago, when Palo Alto commenced its new plans for the downtown and San Antonio Road.

“In the end, if development does happen, then it helps us meet the (regional housing) goals, so that’s not a bad outcome,” Akin said. “It’s just that there will be other consequences that we don’t have any real way to plan for.”

Most Popular