Madison sat quietly at a small table inside Como Community Center, her finger tracing each word as she read.

“Hap. Lum,” Madison said softly, dragging out each sound with careful effort, her digits anchored beneath the words.

The rising third grader’s voice wavered at times as she sounded out “nonsense words,” her brow furrowed in concentration. When she reached a comprehension exercise — selecting the right word to complete a sentence — she paused thoughtfully before circling “afternoon.”

That small decision was a victory. For Madison, and hundreds of children like her, these screenings don’t just offer a summer activity. They represent a first step toward getting the help they need to read on grade level.

If you go

Join us at 6 p.m. July 10 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth for a free screening of “The Truth About Reading,” a look into the literacy problem in America.

This film highlights people who learned to read as adults, and shares proposed solutions for working toward a future where every child learns to read proficiently.

This screening is part of the Modern’s monthly film series, Beyond the Festival, where viewers delve into a world of storytelling that transcends the Lone Star Film Festival. The Fort Worth Report is a co-sponsor of the event.

Free registration is required.

Caroline James, an education consultant for the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, which is helping fund the screenings, said they often flag students who need extra help, sometimes through small clues like when a child makes repeated mistakes.

“Something’s going on with this friend,” James said of one student flagged. “(Those parents are) somebody I’m going to meet with.”

Almost two-thirds of students who live in Fort Worth do not read proficiently, a number that city and school leaders have called a civic crisis. Low literacy rates fuel a host of societal challenges, from poverty to crime, according to officials.

In April, the city formally prioritized literacy in a resolution championed by Mayor Mattie Parker. The resolution pledges citywide support for the 12 school districts serving Fort Worth and commits to partnering with them to ensure universal grade-level reading.

The Literacy Round Up, launched this summer, is the city’s most direct effort yet to fulfill that promise. The program offers free literacy screenings at library branches and Camp Fort Worth community center sites, including Como, Chisholm Trail, Diamond Hill, Riverside, Fire Station and Victory Forest.

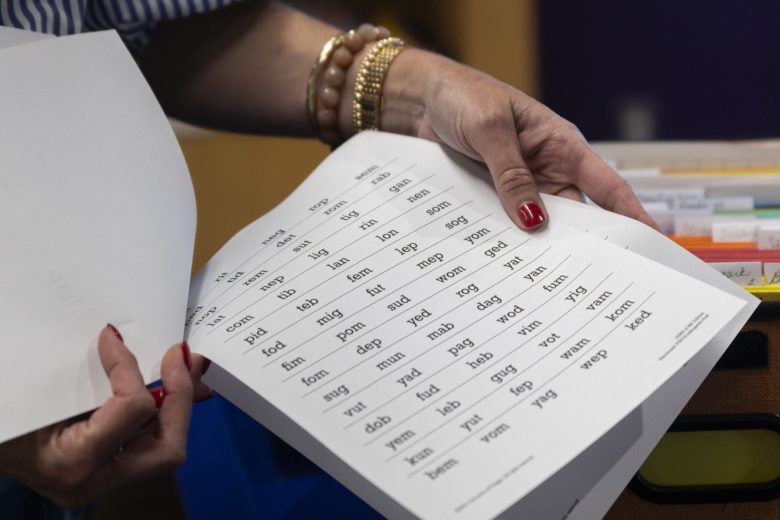

At each site, children are pulled briefly from camp activities for a 10- to 15-minute screening. They read nonsense words, real words and short passages, complete missing-word exercises and comprehension tasks, all while staff score their fluency, accuracy and understanding.

For students like Madison, it’s designed to feel informal. Just a quick check-in.

But behind the scenes, the stakes are high.

Caroline James, an education consultant for the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, shows a section of a dyslexia test June 24, 2025, at the Como Community Center in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

Caroline James, an education consultant for the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, shows a section of a dyslexia test June 24, 2025, at the Como Community Center in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

As of June 26, 400 children have been screened. Of those, 145 — more than a third — showed some level of risk that demands a closer look, James said.

“That doesn’t mean they’re all dyslexic,” she said. “But it means something’s going on. And we owe it to these kids to figure out what.”

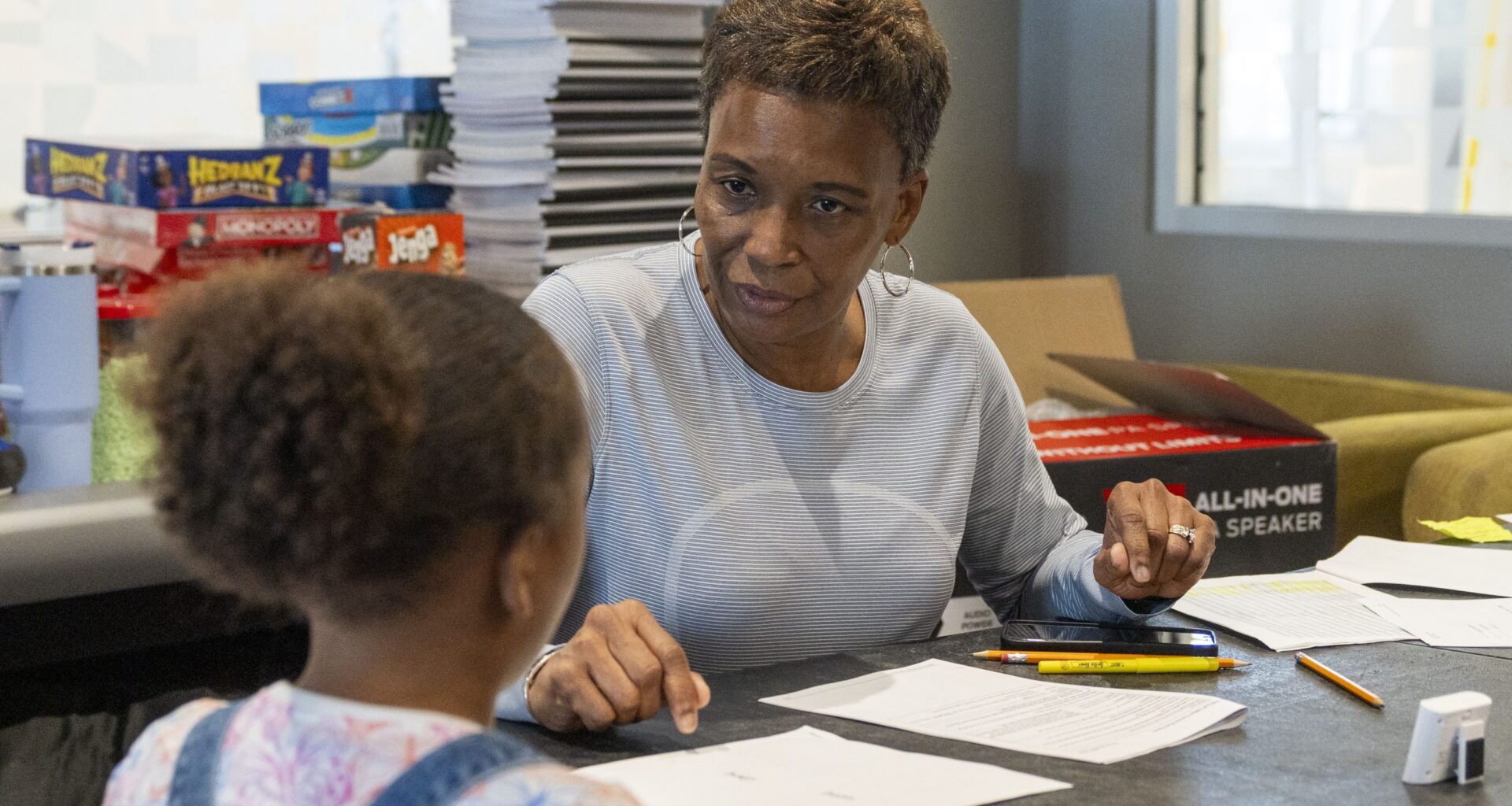

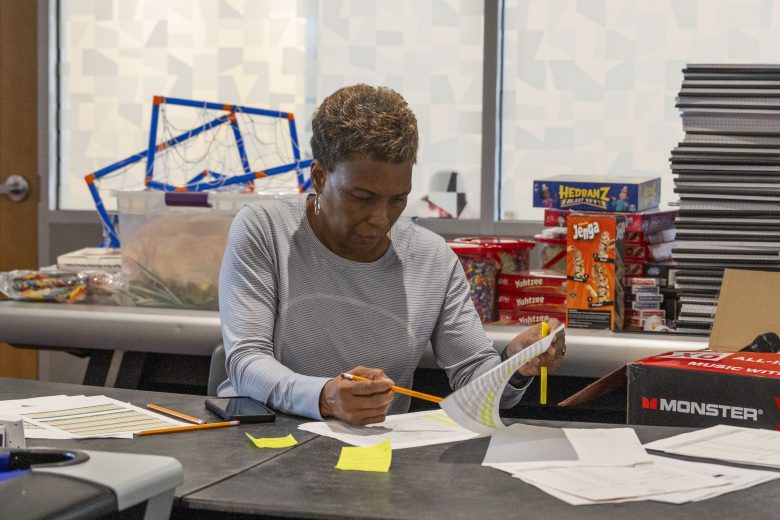

Cynthia Landrum, a Fort Worth ISD teacher and summer literacy specialist, scores tests June 24, 2025, at the Como Community Center in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

Cynthia Landrum, a Fort Worth ISD teacher and summer literacy specialist, scores tests June 24, 2025, at the Como Community Center in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

The screenings aim to identify students who may struggle with decoding, fluency or comprehension — all key building blocks of literacy.

James pointed out that for children with dyslexia, the screenings can flag challenges before they become entrenched.

“If we can find these students early and give them the right intervention, they can get on grade level in about two years and stay there. But we have to act now,” she said.

To do that, the city is asking parents to meet one-on-one with staff to review results. The goal is to have at least 100 families sign up.

Parents receive detailed test results, guidance on how to advocate for their child at school and, if they choose, the support of an advocate through a new partnership with the Rotary Club of Fort Worth.

“We’re trying to help parents ask the right questions,” James said. “You don’t necessarily have to know the answers to these questions, but your teacher should. When you ask them what curriculums they’re using for your student, you should hear the words phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension.”

Lawrence Thompson, the city’s education strategies manager, grew up in poverty and was once wrongly placed in special education classes, he said. His background is why he speaks so passionately about the city’s role in education.

“I’m an ecosystem person,” he said. “If we can strengthen the environment around these kids — not just the classroom, but the whole community — we can change their path.”

That’s part of the reason why the city chose community centers as screening sites. Families trust these locations, Thompson said.

The setting also contributed to increased confidence in the findings.

“It’s a random, broad sample,” James said. “Not just families who already suspect something’s wrong, which gives us a clearer picture.”

Caroline James, an education consultant for the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, goes through her file folder box of tests and results June 24, 2025, at the Como Community Center in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

Caroline James, an education consultant for the Sid W. Richardson Foundation, goes through her file folder box of tests and results June 24, 2025, at the Como Community Center in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

The data gathered so far revealed higher rates of at-risk students at some sites, like Como and Victory Forest, where community needs may be greatest.

For Madison and her peers, the screenings aren’t meant to diagnose, but to start conversations.

“This is like putting your arm in the blood pressure cuff at the pharmacy. If it gives you a high number, you’re not going to call your cardiologist and ask for a heart transplant. But what you are going to do is call your doctor and say, ‘Hey, can we check in? Let’s see what’s going on,’” James said.

Families walk away with a packet of information outlining their rights, timelines for requesting testing from schools and tips for supporting reading at home.

The city hopes the effort will prevent students from falling behind unnoticed and keep them from relying on outdated methods that mask their struggles.

“We’re not teaching kids to guess with picture clues or patterns,” James said. “We’re teaching them to read.”

The work is not over, James said. The city is still seeking more volunteers willing to help parents navigate meetings and push for the right support at school.

Do you want to be a reading advocate for Fort Worth students?

Contact Caroline James at cgentryjames@gmail.com and ask about becoming an advocate for families navigating literacy support in Fort Worth schools.

And the effort goes beyond what happens in classrooms, Thompson said. Kids only spend 13% of their childhood in a classroom, he added.

“We’re doing our part in that 87% of kids’ lives that happen outside the classroom,” he said. “Ultimately, this is about building a city where every child can succeed.”

Matthew Sgroi is an education reporter for the Fort Worth Report. Contact him at matthew.sgroi@fortworthreport.org or @matthewsgroi1.

Disclosure: The Sid W. Richardson Foundation is a financial supporter of the Fort Worth Report.

News decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

Republishing is free for noncommercial entities. Commercial entities are prohibited without a licensing agreement. Contact us for details.