It’s spooky season! So we asked one local historian to tell us where the bones lie — specifically skulls.

Adam Selzer is an expert on the evil and nefarious in Chicago history. The author, Mysterious Chicago tour guide and co-host of the “Tomb Snoopers” podcast will be in local graveyards, at the Lincoln Park Zoo and even on a haunted bus tour through early November, if you’d like to explore the city’s ghostly history.

Here are a few of Selzer’s favorite headcases — and a few others that have been profiled by the Tribune through the decades.

Jean (John) LaLime

The home of John Kinzie. (Chicago Tribune historical illustration)

The home of John Kinzie. (Chicago Tribune historical illustration)

The French-Canadian trader LaLime purchased the property along the Chicago River (today’s Pioneer Court Plaza) in 1800 that was previously owned by Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, Chicago’s first permanent non-native settler. LaLime later sold the land to John Kinzie.

In 1812, Kinzie and LaLime were neighbors, but historical accounts do not portray their relationship as neighborly. There was “bad blood” between them, according to a Tribune article from 1942.

While Kinzie’s name triumphed over LaLime’s in Chicago lore, historical portraits of him aren’t all flattering. A Tribune article from 1966 paints Kinzie as an “aggressive” trader who clashed with some American soldiers stationed at Fort Dearborn. Ann Durkin Keating, a history professor at North Central College in Naperville, describes Kinzie as a “volatile and violent character.”

Did ‘bad blood’ on the American frontier lead to Chicago’s first murder?

Tensions between Kinzie and LaLime came to a head June 17, 1812, when the two men met outside Fort Dearborn, LaLime armed with a pistol and Kinzie with a butcher’s knife. Keating describes the murder that ensued as “premeditated” in her book “Rising Up from Indian Country: The Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago.”

The reasons for the fatal dispute are unknown. Kinzie fled the area afterward and didn’t return until authorities ruled the slaying was in self-defense. Historians do not know whether Kinzie attacked LaLime first or the other way around.

In 1891 — 79 years after the slaying — a partial skeleton thought to belong to LaLime was excavated at Illinois Street and Cass Street (now Wabash Avenue) and given to the Chicago Historical Society, which put it on display for a time. The remains have never been confirmed to belong to LaLime, whose legacy remains nearly as anonymous as his skeleton.

Some say LaLime’s ghost haunts TAO Chicago at 632 N. Dearborn St., which is formerly the site of the Chicago Historical Society and Excalibur night club.

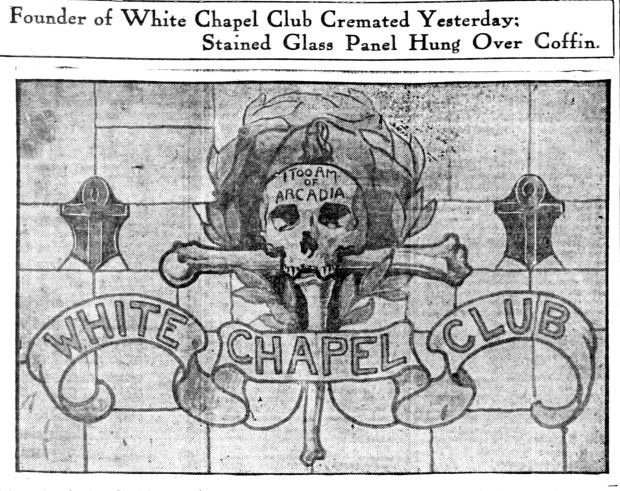

Whitechapel Club

The Chicago Daily Tribune announces the cremation of Dr. Hugh Blake Williams, founder of the Whitechapel Club, on Dec. 7, 1911. (Chicago Tribune)

The Chicago Daily Tribune announces the cremation of Dr. Hugh Blake Williams, founder of the Whitechapel Club, on Dec. 7, 1911. (Chicago Tribune)

One of the city’s most eccentric private organizations, according to the Tribune in 1890, was the Whitechapel Club. The hangout off Newsboys’ Alley on Calhoun Place between Washington and Madison streets took its name from the grisly Jack the Ripper murders in London’s Whitechapel district.

The club consisted of mostly young reporters but also included author Finley Peter Dunne, playwright George Ade and Chicago flag creator Wallace Rice.

Vintage Chicago Tribune: How the Anti-Superstition Society celebrated Friday the 13th

The Whitechapel was most renowned for its gleefully morbid obsession with death. Members could drink spirits out of skulls. A hangman’s noose adorned the club’s walls and ceilings. A huge coffin-shaped dining table, its lid embellished with large brass nails that each bore a member’s name, dominated the main assembly room. “Leave Everything Behind, Ye Who Go Hence,” was the club motto.

But the club’s glory was short-lived, its life snuffed out by one of its own members — who robbed the club and plunged it into debt. Rather than borrow money to pay the debt, the Whitechapel men paid it off themselves and decided to call it quits in 1895, thereby ending a unique chapter of Chicago history.

‘Cow’s skull with calico roses’

“Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses,” by Georgia O’Keefe at the Art Institute of Chicago on Aug. 25, 2014. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

“Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses,” by Georgia O’Keefe at the Art Institute of Chicago on Aug. 25, 2014. (E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune)

The 1931 painting by Wisconsin native Georgia O’Keefe was displayed in the Art Institute of Chicago for the first time in early 1943. She studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago before entering the advertising field — but soon abandoned it.

“Dissatisfied with what she had done so far, she destroyed all her pictures and decided to give up painting as a career,” the Tribune reported. “It was not until she came under the influence of Arthur Dow, the American educationalist, that her interest in painting revived and she entered upon her life work in which she has discovered herself to be an outstanding individualist.”

The painting hangs in the Art Institute’s Arts of the Americas, Gallery 265.

Esther Granger

A resin replica of the skull which was found hidden in the wall of a Batavia home in the late 1970s was on display at a news conference at the Kane County coroner’s office. The coroner said the skull found in the home was identified as Esther Granger, an Indiana teen who died in the 1860s. (R. Christian Smith/The Beacon-News)

A resin replica of the skull which was found hidden in the wall of a Batavia home in the late 1970s was on display at a news conference at the Kane County coroner’s office. The coroner said the skull found in the home was identified as Esther Granger, an Indiana teen who died in the 1860s. (R. Christian Smith/The Beacon-News)

In November 1978, a skull was found behind the wall of a home in the 200 block of East Wilson Street in Batavia. James Skinner, who was remodeling his house, immediately called the Batavia Police Department, which launched an investigation into the person’s identity, he said.

In 2024, the Kane County coroner’s office determined its identity — a 17-year-old woman who died after childbirth in 1865. Granger was born Oct. 26, 1848, and got married at age 16 to Charles Granger, Kane County Coroner Rob Russell said. She was originally buried in Merrillville, and it is not known how exactly her skull ended up in Batavia. However, a “common-sense theory” supported by records and “good reason” is that she was the victim of grave robbing, he said.

A hand-drawn image of what Esther Granger might have looked like based on her skull. (Natalie Murry)

A hand-drawn image of what Esther Granger might have looked like based on her skull. (Natalie Murry)

Batavia Mayor Jeff Schielke, who has also co-authored books on local history, said there are no records of anyone in town knowing Granger or having any relation to her.

The skull somehow ended up in storage at the Batavia Depot Museum, but neither police nor museum records explain why it was sent there, officials said. Batavia police Chief Shawn Mazza said a detective spoke with several investigators who would have worked on the case in the 1970s, but none remembered how or why the skull would have been sent to the museum.

Employees of the museum found a box holding the skull on March 10, 2021, and they immediately called the Batavia police to report the finding, Russell said. DNA testing found a living relative.

Granger’s partial skull was cremated and laid to rest Aug. 22 at West Batavia Cemetery with the permission of her family. It is unclear, however, where exactly the rest of Granger’s body is located.

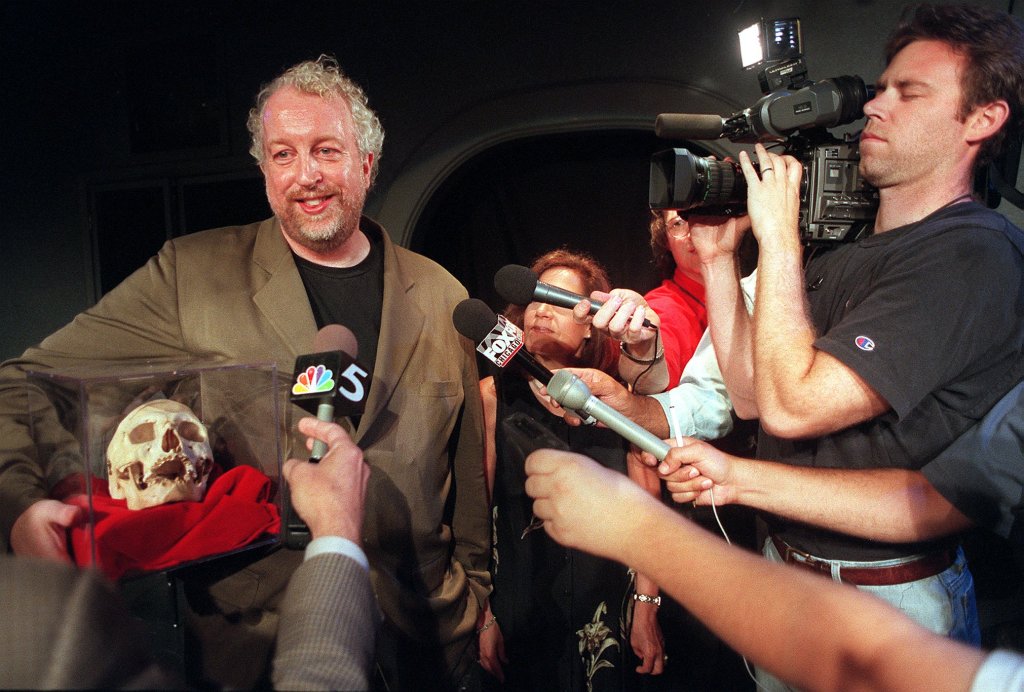

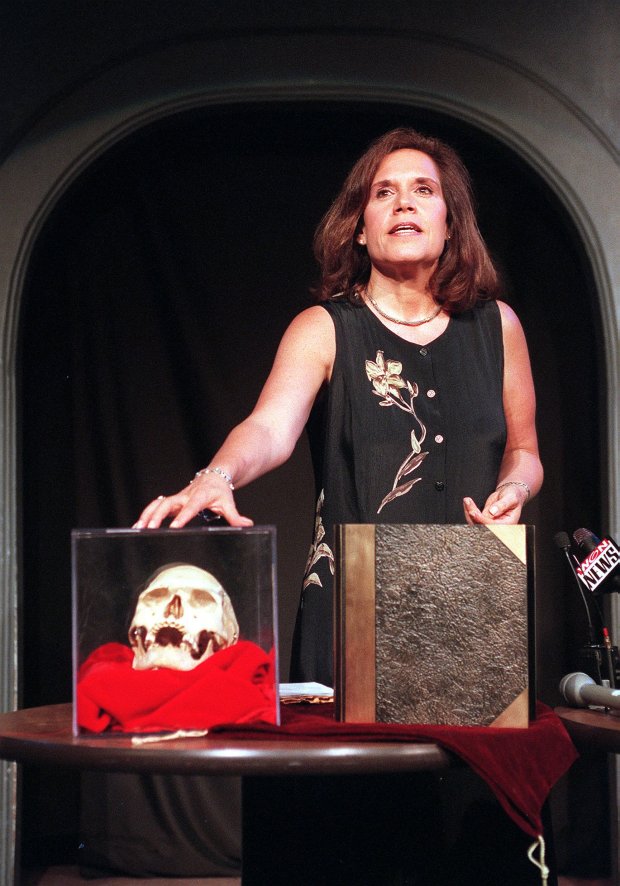

Del Close

Longtime Chicago actor and comedian Del Close bequeathed his skull to the Goodman Theatre to be used in “Hamlet” or any other way deemed appropriate during a ceremony at the Improv Olympic on July 1, 1999. Close founded Improv Olympic with Charna Halpern, shown here, who prepares to present Close’s skull to the Goodman. (Charles Osgood/Chicago Tribune)

Longtime Chicago actor and comedian Del Close bequeathed his skull to the Goodman Theatre to be used in “Hamlet” or any other way deemed appropriate during a ceremony at the Improv Olympic on July 1, 1999. Close founded Improv Olympic with Charna Halpern, shown here, who prepares to present Close’s skull to the Goodman. (Charles Osgood/Chicago Tribune)

Before his death in March 1999, the improv legend willed his skull to the Goodman Theatre for use in stage productions. But the donation couldn’t be done. Instead, a skull purchased from the Anatomical Chart Co. in Skokie was used.

Charna Halpern, co-founder with him of iO Theater and executor of Close’s will, maintained for seven years that the cranium she donated to the Goodman belonged to Close — even after some suspected it was not his. The skull even was a final question on an episode of “Jeopardy!” in 2000.

Second City and its nerdy University of Chicago roots: How a ‘lost cause’ grew into a comedic giant

Halpern stuck to her story in a Page 1 Tribune investigation published in July 2006.

In an issue of The New Yorker, however, Halpern said she tried to carry out Close’s wishes, but pressure from the morgue caused her to buy a skull instead.

Why did Halpern decide to come clean?

“Because the Tribune had already exposed it and I was getting snide responses,” Halpern said.

Sue the T. rex

Sue the T. rex at the Field Museum on Feb. 5, 2018. (Nancy Stone/Chicago Tribune)

Sue the T. rex at the Field Museum on Feb. 5, 2018. (Nancy Stone/Chicago Tribune)

In August 1990, Sue Hendrickson found the largest, most complete and best preserved T. rex to date in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

The Field Museum bought the T. rex named Sue at auction in 1997 for $8.36 million. It went on display in 2000, and moved into new digs upstairs at the museum in 2018.

Vintage Chicago Tribune: Sue the T. rex’s journey to the Field Museum

Sue’s real skull is not mounted atop the body because it became a little deformed over the eons, in part because it is the most frequently studied part of Sue and constant removal would be a burden.

Other famous skulls on display at the Field Museum include the Tsavo lions.

Human impact on chipmunks

Stephanie Smith, a research scientist at the Field Museum, holds a rodent skull that was used in the study on how Chicago’s rodents are adapting to urban living at the Field Museum on July 9, 2025. (Audrey Richardson/Chicago Tribune)

Stephanie Smith, a research scientist at the Field Museum, holds a rodent skull that was used in the study on how Chicago’s rodents are adapting to urban living at the Field Museum on July 9, 2025. (Audrey Richardson/Chicago Tribune)

According to a new study by Field Museum researchers, Chicago’s modern-day rodents have evolved to look quite different from what they did a century ago — mostly because of human development.

They found that over time, Chicago chipmunks have overall gotten larger, but the row of teeth along the side of their jaw has gotten smaller.

“It’s probably related to the food they’re eating,” assistant curator of mammals Anderson Feijó said. “Chipmunks are much more interactive with humans and have access to different kinds of food we eat. So we hypothesize they are eating more soft food and because they require less bite force, which reflects in the tooth rows.”

Similar trends have been documented in other major cities. A 2020 study of rats in New York City found that these East Coast rodents’ teeth have also shrunk over time, similar to those of Chicago chipmunks.

Relics of holy men and women

The Rev. Dennis O’Neill views relics on display in the sanctuary of the Shrine of All Saints at St. Martha Church on April 16, 2019, in Morton Grove. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

The Rev. Dennis O’Neill views relics on display in the sanctuary of the Shrine of All Saints at St. Martha Church on April 16, 2019, in Morton Grove. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Among the more than 3,000 relics displayed at St. Martha of Bethany Church/Shrine of All Saints, 8523 Georgiana Ave., Morton Grove, are pieces of bone, clippings of hair and fabric and statues and paintings that have survived for centuries after the sometimes violent deaths of holy men and women for who they represent.

One special item in the collection is the skull of St. Remacle (Remaclus), a Benedictine bishop who was born in France and became a missionary in Belgium during the 600s.

Tessie Lising of Morton Grove, center, looks over shrine items following a mass in which Archbishop Blase Cupich celebrates mass on All Saints Day at St. Martha Catholic Church where he declared the church an “Archdiocesan Shrine of All Saints” on Nov. 1, 2015 in Morton Grove. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune)

Tessie Lising of Morton Grove, center, looks over shrine items following a mass in which Archbishop Blase Cupich celebrates mass on All Saints Day at St. Martha Catholic Church where he declared the church an “Archdiocesan Shrine of All Saints” on Nov. 1, 2015 in Morton Grove. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune)

As curator, the Rev. Dennis B. O’Neill, pastor emeritus of St. Martha’s, obtains relics for the Shrine of All Saints and searches regularly for new ones to add to the collection. He has written a book that details the origins for many of them.

“I love history,” O’Neill said. “St. Martha is clearly my last parish because I’m getting old, and the building was ideal for it. The bulk of relics were rescued from churches, monasteries, convents, palace chapels and chapels.”

Want more vintage Chicago?

Thanks for reading!

Subscribe to the free Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter, join our Chicagoland history Facebook group, stay current with Today in Chicago History and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Kori Rumore at krumore@chicagotribune.com.