Deeper into the show, “Guernica to Wounded Knee,” a riotous 2012 canvas by the Shoshone-Tatavian painter Stan Natchez, glowers in the corner in a flash-frozen fury. A fiery mash-up of commercialized appropriations of Native American symbols and Pablo Picasso’s 1937 epic, its point can’t be missed: It conflates the Nazis’ bombing trial run of the Spanish town — a favor to dictator-in-waiting Francisco Franco — and the savage 1890 murder of hundreds of Native Americans by the US Army in South Dakota — most of them children and women, some pregnant, killed as they fled for their lives after an order to cease fire.

“Counter History” wasn’t made for this moment, but it’s impossible not to see it through the prism of a culture under widescale threat by a federal administration openly hostile to virtually everything the show holds within it. Trump’s full-force assault on culture and history in the nine months since his inauguration has been broad, aggressive, and highly particular, brazenly rejecting diversity in race, gender, and even idea. After taking aim at the largely-government-funded Smithsonian museum complex, he vaguely threatened that independent museums would be next. Whatever the administration’s powers to do that — not much, it turns out — it was fair to expect a broad chilling effect. But “Counter History” is one among countless hopeful examples to the contrary. While institutions nationwide are hardly unfazed — clawbacks in grants from the National Endowment of the Arts have cut funds for things like public education and diversity programs — their work of revealing and celebrating the dynamic, diverse, fraught evolution of American culture goes on.

Most importantly, maybe, it’s a timely reminder of how culture, broadly, is both kept and advanced in this country — and the limitations of unilateral edict, no matter how high the office, to squelch it.

The Natchez painting at the MFA is a particularly poignant example, tethered as it is to the immediate now. Just a few weeks ago, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth made a showy announcement: that the 19 soldiers who carried out the Wounded Knee massacre would retain the Medals of Honor awarded to them after the attack. A century later, in 1990, Congress apologized to the Sioux people for the killing. In 2024, a federal review considered whether the medals should be rescinded. In September, Hegseth, affirming the soldiers’ honors, said “their place in our nation’s history is no longer up for debate.”

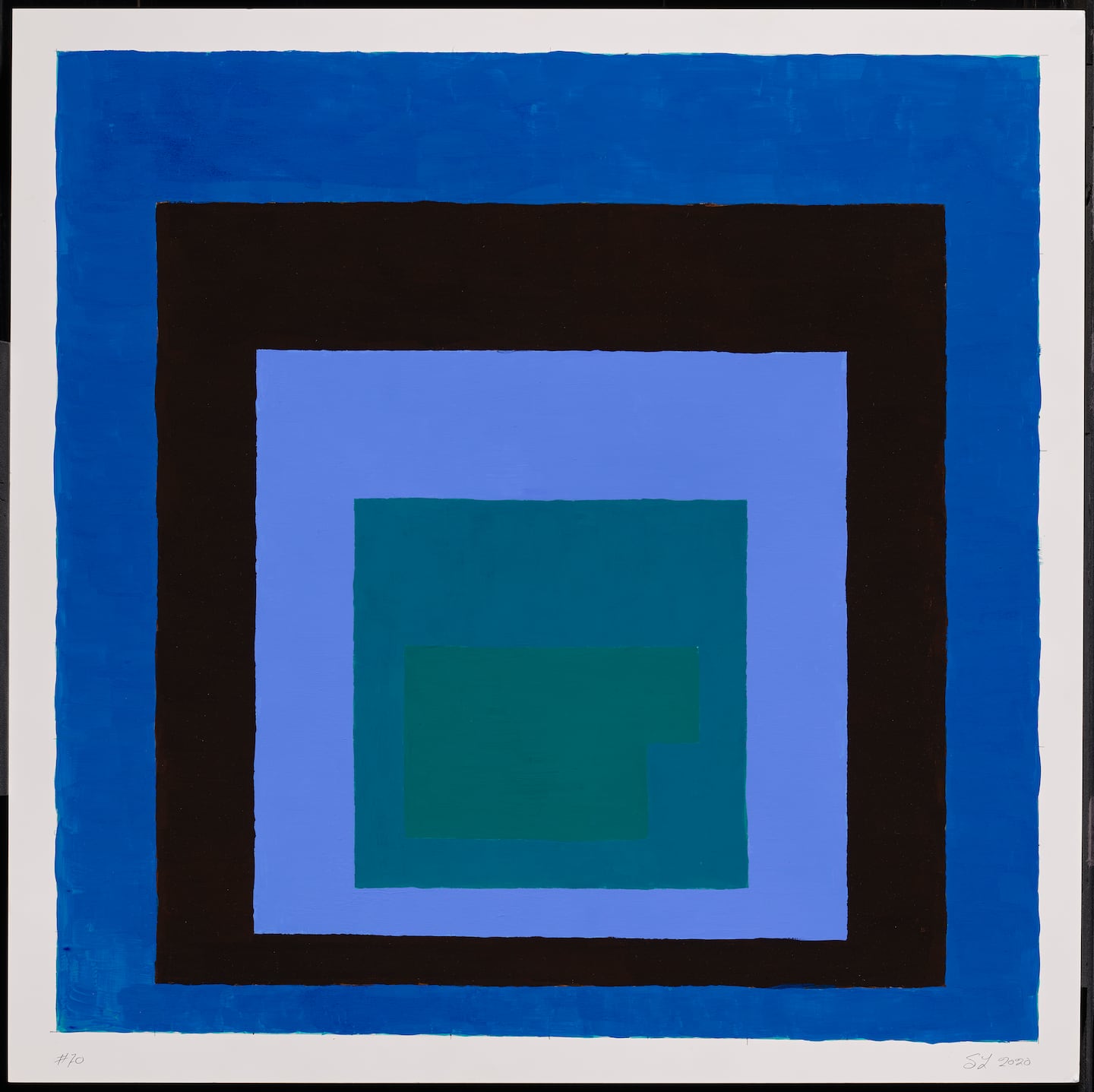

Steve Locke, “Homage to the Auction Block #70,” 2020. (Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Steve Locke, “Homage to the Auction Block #70,” 2020. (Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Debate — and complexity, nuance, curiosity, and conflict — of course, is the lifeblood of culture, and “Counter History” offers plenty. But I’m sure it never expected to be quite so on point. Philip Deloria, a Harvard history professer and member of the Dakota Nation, told the Associated Press that the Hegseth assertion of military valor at Wounded Knee “reflects the way that this administration thinks of history — as something that one person can somehow determine through a magical proclamation.” It’s as though the Natchez painting was made to illustrate that very point.

The painting enjoys pride of place in a slate of artworks that defy that agenda just as openly. The show is a beacon of how easy it is, frankly, to notice how different the America reflected in the nation’s independent cultural institutions is from the vision now in firm view at the White House.

Amy Sherald’s “Trans Forming Liberty,” 2024, on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in April 2025. After the artist pulled her show “American Sublime” from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in September, it was relocated to the Baltimore Museum of Art. Murray Whyte

Amy Sherald’s “Trans Forming Liberty,” 2024, on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in April 2025. After the artist pulled her show “American Sublime” from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in September, it was relocated to the Baltimore Museum of Art. Murray Whyte

Last Sunday “60 Minutes,” under a right-wing assault of its own, aired an interview with the painter Amy Sherald, best known for her portrait of former first lady Michelle Obama. In July, she pulled her triumphant career-spanning survey from the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery amid mounting assaults from the administration on trans people (one of the many portraits in the show is of a trans woman). By September, it had been picked up by the Baltimore Art Museum, just down the road.

It’s no stretch to read that for what it is: that out of easy reach of a hostile administration, independent institutions remain committed to their missions. That’s just one example among countless others countrywide, but even just in New England, there are too many to mention. In Boston, the Institute of Contemporary Art just opened “An Indigenous Present,” an exhibition of contemporary Native American artists’ engagement with abstraction; one of its co-curators, the Choctaw-Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson, is a bona fide art star and the official United States’ artist-rep to the Venice Biennale last year. At the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum — home to notable Titians, Botticellis, Manets, Sargents, and Whistlers — the fall marquee event is an exhibition of Boston painter Alan Rohan Crite, who spent a lifetime painting the Black community around his South End home. “Counter History” will continue with several rotations of new works well into 2026; but the museum is also hosting the first major survey in almost 20 years of the work of Martin Puryear, a senior American artist, who is Black, and whose most recent signature work is a tribute to the enslaved woman who bore Thomas Jefferson six children, Sally Hemings.

Allan Rohan Crite, “School’s Out,” 1936. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library

Allan Rohan Crite, “School’s Out,” 1936. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library

A little farther afield, at Mass MoCA in North Adams, the feature draw is Vincent Valdez’s “Just a Dream …,” a visceral exploration, through his paintings and drawings, of fractious themes of American society like border walls, lynchings, and the Ku Klux Klan. At the nearby Clark Institute, two exhibitions of women artists recently closed after a summerlong run: “Berenice Abbott’s Modern Lens,” on the renowned American photographer’s work in the early 20th century; and “A Room of Her Own: Women Artist-Activists in Britain, 1875-1945.”

All summer, it seemed, women dominated the art world calendar: A dazzling exhibition of the largely-forgotten Dutch Golden Age master painter Rachel Rusych opened in August at the MFA, following the immersive dread of Chiaru Shiota’s “Homeless Home,” the Japanese artist’s plunge into the traumas of migration at the ICA Watershed. Look north to Maine and you’ll find the Portland Museum of Art’s just opened an exhibition of the work of Grace Hartigan, overlooked among the Abstract Expressionist scene she hung out with in no small part because she was a woman. Meanwhile, at Colby College, in Waterville, Gertrude Abercrombie, a habituee of the Chicago jazz scene at midcentury and a painter of dazzlingly enigmatic semi-surreal scenes left largely out of the American canon, is taking her first ever star turn.

Chiharu Shiota’s “Homeless Home” at the ICA Watershed in the summer of 2025.PHILIP KEITH/NYT

Chiharu Shiota’s “Homeless Home” at the ICA Watershed in the summer of 2025.PHILIP KEITH/NYT

It’s a lot. I could go on. Which says something, I think, about the health of American cultural institutions in fraught times, much of it good. Across their dizzying breadth runs a common thread: a defiant curiosity and commitment to continue to be expansive — to want to know more, and to reveal more about the American experience, despite pressures to the contrary.

The simple fact that they stand outside government structure as independent nonprofits — the status of the vast majority of cultural institutions of all kinds — matters. Among the Trump administration’s first targets were universities nationwide, threatened with funding clawbacks and worse if they refused to hew to its vision. After a handful of high-profile acquiescences, universities have largely re-girded; prominent institutions have recently rejected overtures for preferential treatment in exchange for greater administration oversight. Universities stand to lose a lot — billions, in fact — but have courageously chosen principles over ease. Major museums receive far less federal funding, but being on the front lines of public culture makes them no less courageous.

Winifred Knights, “The Deluge,” 1920s. Tate. Included in the Clark Art Institute’s recent “A Room of Her Own: Women Artists in Britain, 1875–1945.” Tate Gallery

Winifred Knights, “The Deluge,” 1920s. Tate. Included in the Clark Art Institute’s recent “A Room of Her Own: Women Artists in Britain, 1875–1945.” Tate Gallery

Surely, smaller institutions across the cultural spectrum have suffered: A New York Times story recently found that a third of the country’s 35,000 museums have lost some government funding; here at home, a survey by MASSCreative, an arts advocacy nonprofit, found that 83 percent of cultural organizations in New England that lost federal funding that had BIPOC-related programming. That has left well-endowed large-scale institutions to carry the torch, and by and large, they are.

The study of cultural history has always been a process of revision and refinement. Those efforts, while imperfect, have been nothing short of heroic, embracing American cultural history as the complex and uneven landscape it’s always been. Among women and non-white artists in particular, this reconfiguration of priorities has provided a bounty of riches; it could hardly be otherwise, given their age-old neglect. As recently as 2019, a study at Williams College found that 87 percent of artists in US museum collections are men, and 85 percent are white.

Kay WalkingStick, “Chief Joseph Series,” 1974-76, named for the Nez Perce hero who led his people more than 1,000 miles north in an attempt to escape the brutal incursions of the American Army, clearing a path for westward expansion after the Civil War.Mel Taing

Kay WalkingStick, “Chief Joseph Series,” 1974-76, named for the Nez Perce hero who led his people more than 1,000 miles north in an attempt to escape the brutal incursions of the American Army, clearing a path for westward expansion after the Civil War.Mel Taing

It should surprise no one that there’s no quick fix to that lopsided representation; on its own, it tells a story of America (and not only America) not to be ignored. So, the focus should be not only on percentages and data but the stories these museums tell. They are, typically, compelling. “An Indigenous Present” ties Native American abstraction to the American Indian Movement of the 1970s, a reawakening of Indigenous culture and its contemporary departure point; the Gardner honors Crite with his first museum show, unlocking the urban history outside its door that the institution spent much of the first century of its existence ignoring in favor of Old Masters.

That’s a small handful of what we’ve missed, generation to generation, and just a taste of what’s left to come to light as those narrow histories continue to crack open and the light floods in. Whatever the cultural priority from on high, the cracks keep growing wider — because culture is evolution, with a momentum and will of its own.

Murray Whyte can be reached at murray.whyte@globe.com. Follow him @TheMurrayWhyte.