Last week, the New York Times published a piece by Willy Staley about a skatepark in Malmö, Sweden that was built from pieces of Philadelphia’s former LOVE Park.

LOVE Park, back in the day.

LOVE Park, back in the day.

Located at the center of Philadelphia’s downtown, Love Park’s granite benches and ledges improbably turned a public space into a skateboarding mecca. But because Philadelphia in the 1990s and early 2000s was trying to jumpstart a downtown rebound, envisioning a city that appealed to white collar workers, the City thwarted skateboarding at every turn, first banning skateboarding and then eventually renovating the park in the mid-2010s. (I highly recommend this photo essay about the original LOVE Park’s last days.)

Now, that same, board-scratched granite — having reached icon status in the skateosphere — is serving skaters 4,000 miles away.

A decade since it was transformed into a boring, graceless, placeless plane, it’s been easy to be nostalgic for and romanticize the public space as a grimy grotto. But one thing no one can deny about the old LOVE Park: Young people — especially young men — wanted to hang out there.

Maybe in the past we spent too much time catering to men in our public spaces. But now, as I’ve written about the cult of brightly-painted movable chairs, our public spaces are increasingly centered around sitting rather than physical activity, around consumption rather than hanging out — and around ensuring that the “wrong people” don’t use them. Few of our public spaces seem to be speaking not just to young men — particularly less affluent and educated young men.

At the same time, there is now great concern that these men are drifting into the online manosphere, losing their money in online sports betting, watching AI porn, experiencing brainrot. (Maybe an exaggeration of the situation, maybe not.) But for all the Scott Galloway podcasts I’ve listened to and Richard V Reeves and Aaron M. Renn posts I’ve read about the problems of young men, I’ve yet to hear any of them mention urban planning, placemaking, or retail as part of the solution. As if the places where we connect (or don’t) with other human beings play no role in our societal unraveling.

Robert Indiana’s iconic LOVE sculpture, the unofficial namesake of JFK Plaza in Center City, Philadelphia. We can get young men back outside

Robert Indiana’s iconic LOVE sculpture, the unofficial namesake of JFK Plaza in Center City, Philadelphia. We can get young men back outside

For a long time, we’ve been trying to make cities safer and more amenable to women — and with good reason. Women in cities are more likely to be verbally and physically harassed (or worse). They’re also more likely to navigate the city with children. I’m in agreement that we need policies that make city life easier and better for women.

But while we may have built cities that work well for men to take transit or walk late at night, it can also be true that we haven’t done a particularly good job of building public spaces for boys and men to build social connections.

We could be thinking more about how to integrate spaces that are naturally compelling to young men. As Staley writes, Malmö has been incorporating skateboarding into the city:

One minor but fascinating element of Malmö’s postindustrial turnaround has been an effort to incorporate skateboarding into the fabric of the city. Even more tolerant urban governments in the United States tend to cordon skaters off in parks, sometimes very nice ones, but in southern Sweden, they’ve been trying something different: treating skateboarding like a unique source of vitality rather than a nuisance to be managed.

For fun, try reading this passage again, but replacing “skateboarding” or “skaters” with “young men.”

What might that look like? Sports certainly seems like an easy entry point. Basketball courts, handball courts, ping pong tables all can be incorporated into cityscapes easily.

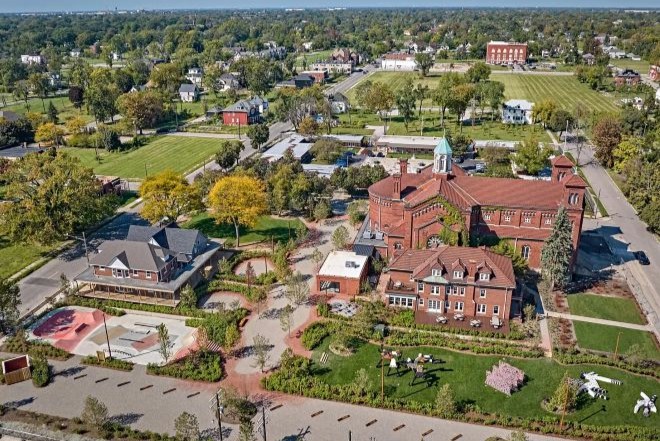

The Shepherd Project, Detroit, MI.

The Shepherd Project, Detroit, MI.

As I’ve written, The Shepherd project in Detroit has a skateboarding park as part of a larger cultural complex that includes an art gallery, hotel, and restaurant.

Tom Lee Park in Memphis, TN.

Tom Lee Park in Memphis, TN.

At Tom Lee Park in Memphis, basketball and pickleball courts are integrated into a 30-acre city park.

But what I think the Malmö example is suggesting is a mentality of embracing “nuisance” as vitality. San Francisco’s U.N. Plaza, which (on point) embraced skateboarding, has transformed a desolate expanse into a skateboarding community destination perhaps with this mindset.

Skateboarding on granite from the old LOVE Park in Malmö, Sweden.

Skateboarding on granite from the old LOVE Park in Malmö, Sweden.

Would simply designing spaces with young men as one of the desired users be enough to change how we build our public spaces?

Conor Dougherty’s piece also notes that catering to a specific group of people has re-inhabited U.N. Plaza:

What the transformation of U.N. Plaza does show, however, is that attempts at urban revival can go a long way for relatively little money when they attract a natural constituency of users.

When you think about the most habitually used public spaces these days, many of them are places for dedicated users: the dog park, the playground, the community garden. Those are places that have specifically been built with the needs of dog owners, kids, and gardeners in mind. No shame about that. It also sounds like the hobby economy could be useful here.

We may not need a whole placemaking movement just for young men, but we do need to recognize that we have been creating few spaces that are giving men opportunities to hang out, and that this is one more thing we should be doing if we truly want men to get off their computers and video games and reengage with the real world again. What that looks like in the 2020s, we’ve yet to figure out.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER

MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER