Two bright blue rivers run across a desolate scene in the “Toxicological Tablecloth.” The massive linen spread, measuring 85 feet wide and 85 feet long, depicts dozens of oil drums spilling rainbow sludge onto what’s left of the natural world. Transmission towers, naval mines and acid rain clouds dot the landscape, rendered in a pale, dusty brown. Only a few sheep have survived.

- INSIDE THE ARCHIVES

- PhillyVoice peeks into the collections at different museums in the city, highlighting unique and significant items you won’t typically find on display.

The charged table runner, which comes with a provocative set of dishes, has been with the Fabric Workshop and Museum since the 1980s, when artist Rebecca Howland took up residency at the Arch Street institute. The mixed media work is emblematic of the FWM, known for its screen-printing workshop but home to a wide array of furniture, garments, umbrellas, sculptures and ceramics.

Setting the table

“Toxicological Tablecloth” is really an entire tablescape. Howland designed a “money bag” vase to sit in the center, and accents like a lung cancer ashtray (a shallow pink ceramic lung with a gray, diseased mass) and candlestick holder formed from the smoky fires of gas companies (Shell, Sunoco and Arco, to be precise).

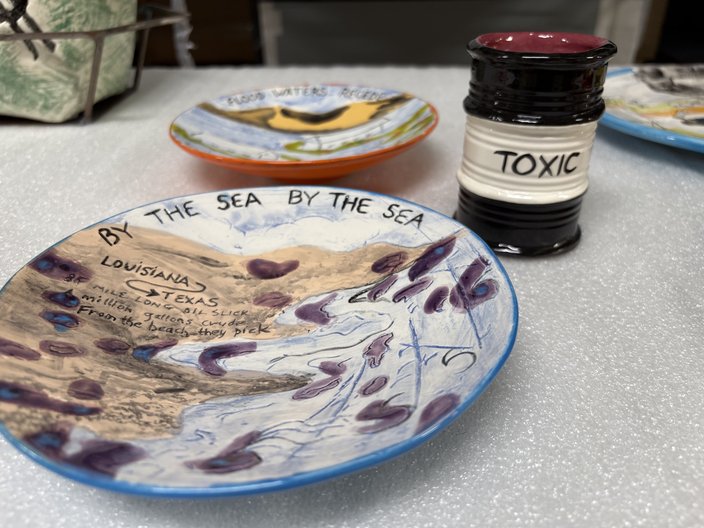

The artist also crafted cups to resemble drums of toxic waste and a stack of plates illustrating ecological disasters. Some are broad tableaus of chemical companies belching out “poison,” while others reference specific crises. One dish commemorates the 85-mile oil slick that spread across the Gulf Coast in 1984, eventually dousing Texas beaches in a “sickening” goop. Another combines two catastrophes: the flooding in Times Beach, Missouri, that spread dioxin through the town and forced the permanent relocation of its roughly 2,000 residents and the mine fire in Centralia, Pennsylvania, that’s been burning since 1962.

The ‘Toxicological Tablecloth’ spread includes cups that look like drums of toxic waste.

“I think she’s being really playful, but also maybe trying to provoke us a bit with this table spread,” said Justin Rubich, senior marketing and communications manager for FWM. “It’s like from farm to table, but instead it makes you kind of nervous about not just where your food is coming from, but also what’s in the ground. Or how it’s getting here and maybe the consequences of the systems we take for granted.”

A ceramic plate from Rebecca Howland’s ‘Toxicological Tablecloth’ references the Superfund site at Times Beach, Missouri, and the still-burning mine fire in Centralia, Pennsylvania.

Howland’s been inspiring queasy feelings like these throughout her nearly five-decade career. The New York-based artist, who grew up in Niagara Falls, remembers seeing oil refinery fires, gas storage tanks and “armies of transmission towers” as a girl. These startling images repeat across her work in pieces like “Oil Tankers on Fire” and the “Transmission Towers” sculpture series. “Toxicological Table” incorporates them all.

“My table is the opposite of the old saying ‘eat the rich,'” Howland said in an artist statement. “It shows how the consumer is consumed by industry – how we’re all being poisoned in our day-to-day life.”

Fax machines and pig guts

The Fabric Workshop and Museum has been working with artists like Howland since 1977. Curator Marion Boulton Stroud founded the organization with two goals in mind: encouraging creatives to experiment with fabric and training apprentices in textile design and production. On the building’s sixth floor, students of all ages still learn how to screen-print. Collaboration is key, since the wide tables make any task a two-person job. Partners pass a squeegee back and forth to press the ink through a mesh screen onto the entire swath of fabric.

That collaborative spirit is also seen in the artist-in-residence program. FWM works closely with the enrolled sculptors, ceramicists and other visual artists to execute their vision, wherever they are in the world. Though some alum have lived in or visited Philadelphia during their residencies, many communicate ideas with the museum remotely. Around the time Howland was in the program, FWM sent messages through fax machines and the postal service.

“It doesn’t work unlike that today,” Rubich said. “Our studio still will send things in the mail and ask artists to approve or for their thoughts … you’ll see in some of the faxes that are in our archive, it’s not all super formal. They’re really personable, really sweet. Sometimes there’s little drawings and notes, side notes and stuff. Like, they’re clearly writing on a typewriter and then dropping it in the fax, but there’s a lot of personality in them. It’s kind of sweet seeing the kind of relationships build even when people aren’t in the same place.”

The Fabric Workshop and Museum stores bolts of screen-printed fabric in its archives.

Since the museum is in the habit of collecting these messages and other ephemera from the creative process into boxes, it’s well-equipped to reprint fabric designs. As Rubich explains, a studio team of new artists can easily re-create something developed at FWM decades ago by pulling out the old mylar films, fabric swatches and notes. The museum gift shop sells bolts of screen-printed textiles by the yard alongside ties, tees and totes printed with past patterns.

Artists have also screen-printed umbrellas, seen here in protective storage, for the Fabric Workshop and Museum.

The museum staff’s dedication to faithful re-creations isn’t always pretty. Justin Hall, the senior registrar and collections manager, often tells people about “2 x (ø60 x 190),” two cylindrical columns by Polish sculptor Miroslaw Balka in the collection. The forms were fashioned out of dried and layered pig intestines, with hundreds more blown-up inside. The last time it went back on display, Hall had to pick up fresh supplies from the Italian Market, blow them up with a turkey baster and painstakingly add them himself.

“I’ve only done it once, but I’m like, never again,” he said. “Interns, whoever’s new, has to do it next time.”

As the museum and workshop approaches its 50th anniversary, it’s trying to attract new audiences. FWM recently updated its digital database, which Rubich admits was “really static.” It now shows off almost 500 of the roughly 5,000 items in the museum’s collection, including Balka’s columns and Howland’s “Toxicological Tablecloth.” As the digital catalog grows, Rubich hopes more people realize the breadth of the museum’s offerings.

“If you look at what’s published on online versus the vast history we have, it’s actually a drop in the bucket,” he said. “People just don’t know.

“I think what we want to get away from is this hidden gem aspect. Or if you know, you know. I think we want to be more discoverable. It’s great that there have been people who have always known about the workshop, have always come and seen our shows. … But it’d be great for people who we’re new to, to be able to dig in and go down the rabbit hole and find out about all the great projects we’ve been a part of.”

Follow Kristin & PhillyVoice on Twitter: @kristin_hunt

| @thePhillyVoice

Like us on Facebook: PhillyVoice

Have a news tip? Let us know.