Southwest Research Institute visitors might be surprised to find a 7-foot-tall metal statue of the abominable snowman.

The research institute’s mythical mascot can be found everywhere. Staff dress the metal yeti up for holidays and move him around different parts of the 1,500-acre research campus. They show him off on social media and hand out Yeti-themed stickers to library visitors. Yeti statues and knick-knacks adorn SwRI CEO and President Adam Hamilton’s office.

The unlikely and unofficial mascot is an homage to SwRI’s founder — Tom Slick, the most eccentric Texas millionaire you’ve probably never heard of — who spent years searching for the yeti and other creatures in the 1950s.

It’s difficult to summarize Slick’s time on Earth and the impact he left on San Antonio. Oilman, rancher, scientist, philanthropist, inventor, adventurer, cryptozoologist. He hunted mythical monsters, founded three research institutes with a vision of turning San Antonio into “Science City,” grew his father’s oil business, maintained an extensive art collection and authored books on achieving world peace.

The only thing he couldn’t seem to do was sit still for too long.

And he did all of this by his mid-40s. In 1962, while returning to the U.S. from a Canadian excursion, the 46-year-old Slick died in a plane crash.

Never miss San Antonio Report’s biggest stories.

Sign up for The Recap, a newsletter rundown of the most important news, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Slick’s niece, Catherine Nixon Cooke, was 11 when he died. She has since authored a book about her uncle, “Tom Slick, Mystery Hunter,” and led the Slick-founded Mind Science Foundation for 15 years.

“Those of us who spent time with him realized that he was a real life ‘Indiana Jones’ long before that archetype had a name,” Cooke said. “Most of us who heard his fabulous tales as children became curious and adventurous.”

Nessie and ‘Sweet William’

Thomas Baker Slick Jr. was born in 1916 in the small town of Clarion, Pennsylvania.

His father, Slick Sr., would become one of the most accomplished independent oil operators in the Southwest. Better known as “Lucky Tom” and “King of the Wildcatters,” Slick Sr. built a fortune drilling wildcat wells, a high-risk method of discovering oil fields that is essentially sticking a drill in the ground and crossing your fingers.

Tom Slick with the cast of his legendary yeti footprint. Credit: Courtesy / Catherine Nixon Cooke

Tom Slick with the cast of his legendary yeti footprint. Credit: Courtesy / Catherine Nixon Cooke

The Slicks were constantly on the move, between their Pennsylvania hometown, Oklahoma and San Antonio. In 1930, coincidentally at the same age his son would die, Slick Sr. passed away from a brain bleed. He left his children $15 million, the equivalent of what would be $290 million in 2025 dollars.

From an early age, Slick was interested in science and biology, as well as the genetic engineering of animals. This, combined with the sense of adventurousness and daring his parents instilled in him, set the stage for Slick’s ventures in adulthood.

According to Loren Coleman, a cryptozoologist, author and TV personality, who wrote a book about Slick’s adventures: “Tom Slick and the Search for the Yeti” in 1989, Slick embarked on his first hunt for the unknown while in college.

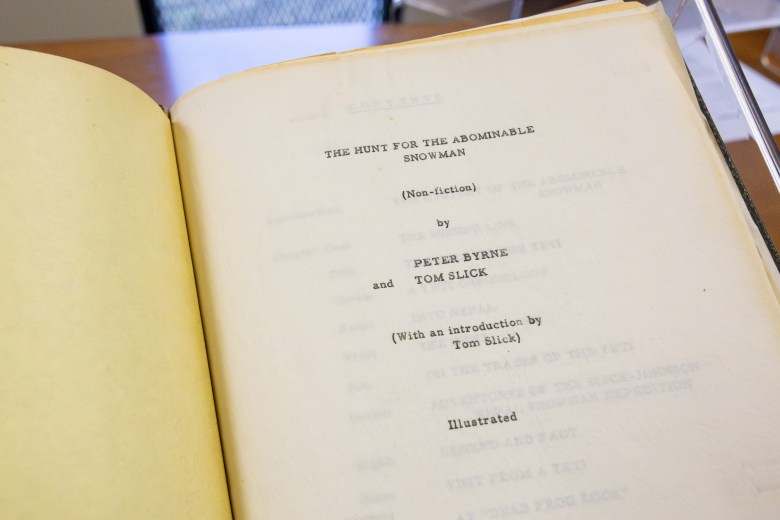

Southwest Research Institute has a non-fiction book called “The Hunt for the Abominable Snowman” in its rare books collection authored by Peter Byrne and Tom Slick. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Southwest Research Institute has a non-fiction book called “The Hunt for the Abominable Snowman” in its rare books collection authored by Peter Byrne and Tom Slick. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

In 1937, as a pre-medicine science and biology student at Yale, Slick urged a group of friends to take a detour during their summer vacation in Europe. The group went to Scotland’s Loch Ness lake in search of the Loch Ness Monster, otherwise known as “Nessie.” The group interviewed locals and searched the water’s surface, but didn’t spot anything resembling a long-necked lake creature.

Visitors to San Antonio’s Tom Slick Park can spot a metal Nessie statue partially submerged in the park’s pond.

Also while at Yale, Slick became infatuated with a “Ripley’s Believe It or Not!” newspaper column concerning a strange-looking barn animal that its owner claimed was a “hoat,” a hybrid animal that resulted from the mating of a hog and a goat. This “hoat” was put on display by its owner in Oklahoma and then featured in Ripley’s column.

Slick, hellbent on breeding the animal, tracked down the owner within a month and bought it for $100, bringing it back to his mother’s farm in Oklahoma. According to Slick’s sister, Betty Slick Moorman, he kept a photo of the animal (which he called “Sweet William”) in his wallet, showing it to girls he went on dates with.

Perhaps looking for an extra wingman, Slick tried to breed the “hoat” with other hogs and goats, but failed. That’s because whatever odd-looking barn animal Slick brought back to San Antonio was almost certainly not a hog-goat, animals that are too genetically different to produce offspring.

Less strangely, years later, Slick helped cross-breed American Angus and Brahman cattle, which resulted in the Brangus, today a common choice for beef farmers in hotter climates.

Slick’s monster hunting efforts would then take a hiatus, starting with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Oil drilling, diamond mining and Science City

For Slick, the years to follow were productive, to say the least.

He established his first research institute at the age of 25 in 1941, called the Foundation of Applied Research, which would become the Southwest Foundation for Research and Education. Today it’s known as Texas Biomedical Research Institute.

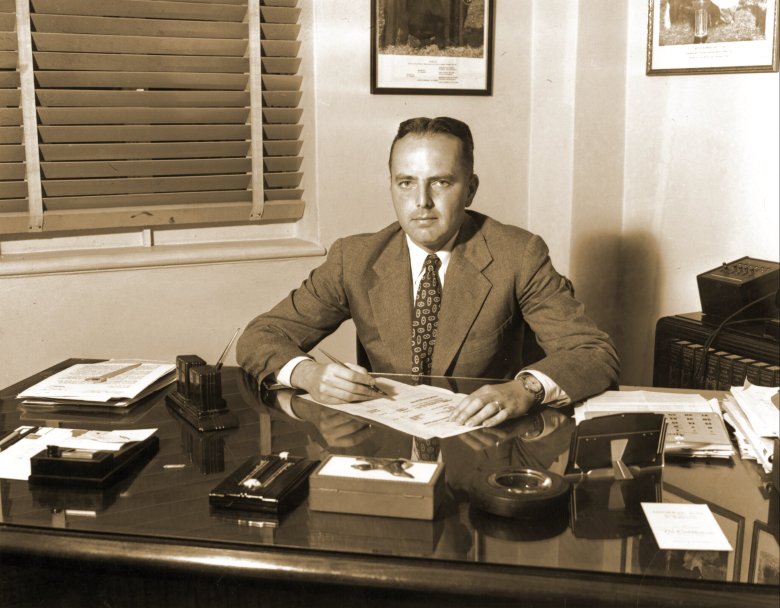

Tom Slick was just 25 years old when he established what is today Texas Biomedical Research Institute. It will celebrate its 85th anniversary in 2026. Credit: Courtesy / Catherine Nixon Cooke

Tom Slick was just 25 years old when he established what is today Texas Biomedical Research Institute. It will celebrate its 85th anniversary in 2026. Credit: Courtesy / Catherine Nixon Cooke

During WWII, Slick served as a “dollar-a-year-man,” working with the U.S. government without direct compensation to mobilize and manage industry resources for the war effort, and later serving in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific.

After the war, Slick helped his brother Earl run the cargo airliner he founded, Slick Airways. He also continued growing his father’s oil operations, helping discover one of the most significant post-WWII oilfield finds in the U.S., the Benedum Field in West Texas in 1947. The same year, he set up a second research institute on his sprawling ranch: Southwest Research Institute.

Slick also owned a mining company that bought abandoned mines and attempted to squeeze any remaining profits from them with new technology. During a 1956 diamond-hunting expedition in South America, Slick’s plane was forced to land in the remote jungles of British Guiana, now Guyana. He reportedly spent two weeks living with the Waiwai tribe — a small Indigenous group in Northern Brazil — surviving on parrot meat, before returning home.

In 1948, Slick co-invented a new construction method to build multi-story buildings, known as lift-slab construction or the Youtz-Slick Method.

Slick cultivated an extensive art collection during his world travels, now dispersed among family members, the McNay Art Museum, the Witte Museum and others. Slick authored two books, in 1951 and 1958, on his vision for ending global conflict and bringing about world peace.

This is really only the tip of the iceberg on Slick. He had his hands in a number of other pursuits, like early research on birth control, IVF and alternative medicine, just to name a few.

The yeti expedition

Cryptozoology, a subculture that seeks undiscovered and mythical animals, emerged in the 1950s. In fact, Coleman describes Slick as one of the first cryptozoologists — those who search for hidden animals not yet acknowledged by science, as he puts it.

Slick’s search for the yeti was more scientific than it would be considered today. Much of the Himalayas hadn’t been explored, so the idea that an undiscovered ape resided in the mountains wasn’t as far-fetched to scientists at the time.

“I have a little bias,” Hamilton, the SwRI president, said. “But a lot of people would call it a monster-hunting adventure. I don’t know so much about that. To me, it’s almost like a fact-finding expedition.”

In India, Slick heard reports from locals of an ape-like creature that roamed the Himalayan Mountains. Slick suspected that this creature, which he described as “a fierce and hairy ape-man, at least eight feet tall,” could be an evolutionary “missing link” to help explain the jump between earlier primates and Homo sapiens.

According to Coleman’s account, Slick went on several reconnaissance missions gathering information, and in 1957, he returned to Nepal with a small crew, guns, crossbows and ammunition, ready to prove the existence of the yeti by bringing back a specimen “alive or dead.”

Slick’s Texan approach earned him a “good deal of bad press” abroad, Coleman wrote. Slick would return to Texas without a yeti, but with a footprint, hair and droppings that he believed belonged to one.

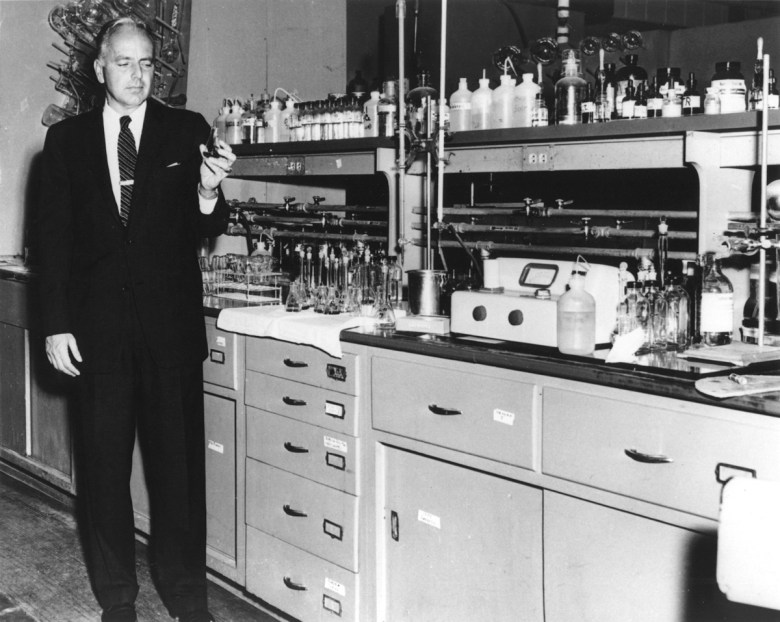

An undated photo of Tom Slick in a lab. Credit: Courtesy / Texas Biomedical Research Institute

An undated photo of Tom Slick in a lab. Credit: Courtesy / Texas Biomedical Research Institute

Cooke recalls marveling at a yeti footprint cast that adorned Slick’s dining room table and the stories he’d tell about the expedition.

It was the last yeti expedition Slick participated in, though he would help organize others. That’s because Slick and his crew also had a near-death experience when the bus they were sleeping on rolled down a hill. Everyone got out okay, but Slick injured his knee. Seeking to “keep his mother’s blood pressure in the normal range,” as Coleman put it, Slick continued organizing searches but didn’t personally participate.

Slick wasn’t done monster hunting though. His attention turned to the yeti’s long-long, forest-residing cousin, Sasquatch. Slick participated in expeditions in the Pacific Northwest and Canada, where Bigfoot sightings had been reported. Slick apparently collected samples during these trips as well, that he said were from the abominable woodsman, but his involvement in the searches ended in 1962, and it’s unclear where the samples ended up.

Slick sought other mystery animals — though these searches seem less involved than that of the yeti — including the “orang pendek,” a hobbit-like creature in Indonesian folklore rumored (but never recorded) to inhabit the Island of Sumatra, giant salamanders in California and an Alaskan lake monster.

Slick’s Legacy

Outside of the research institutes, where yeti statues, portraits and busts of Slick can be found everywhere, Slick is not too well known. Besides the books by his niece and Coleman, an eight-episode dramatized podcast series featuring actor Owen Wilson as Slick was released last year, chronicling his monster-hunting adventures.

Although Slick didn’t bring back a yeti from the East, he did return to San Antonio with an interest in the human mind. According to Cooke, Slick spent time with Buddhist monks and the Dalai Lama in Tibet. Having observed what he described as “psychokinetic activity,” holy men he said could move things with their mind, Slick established the Mind Science Foundation in 1958.

Slick even considered the foundation — which supports neuroscientific research through grants — as his most important undertaking, given the “tremendous potential” of the human mind.

Although the Mind Science Foundation has not cracked telekinesis yet, and neither research institute has found the yeti or Sasquatch (or so we’re told), the institutes and foundation have made significant scientific impacts in San Antonio and internationally.

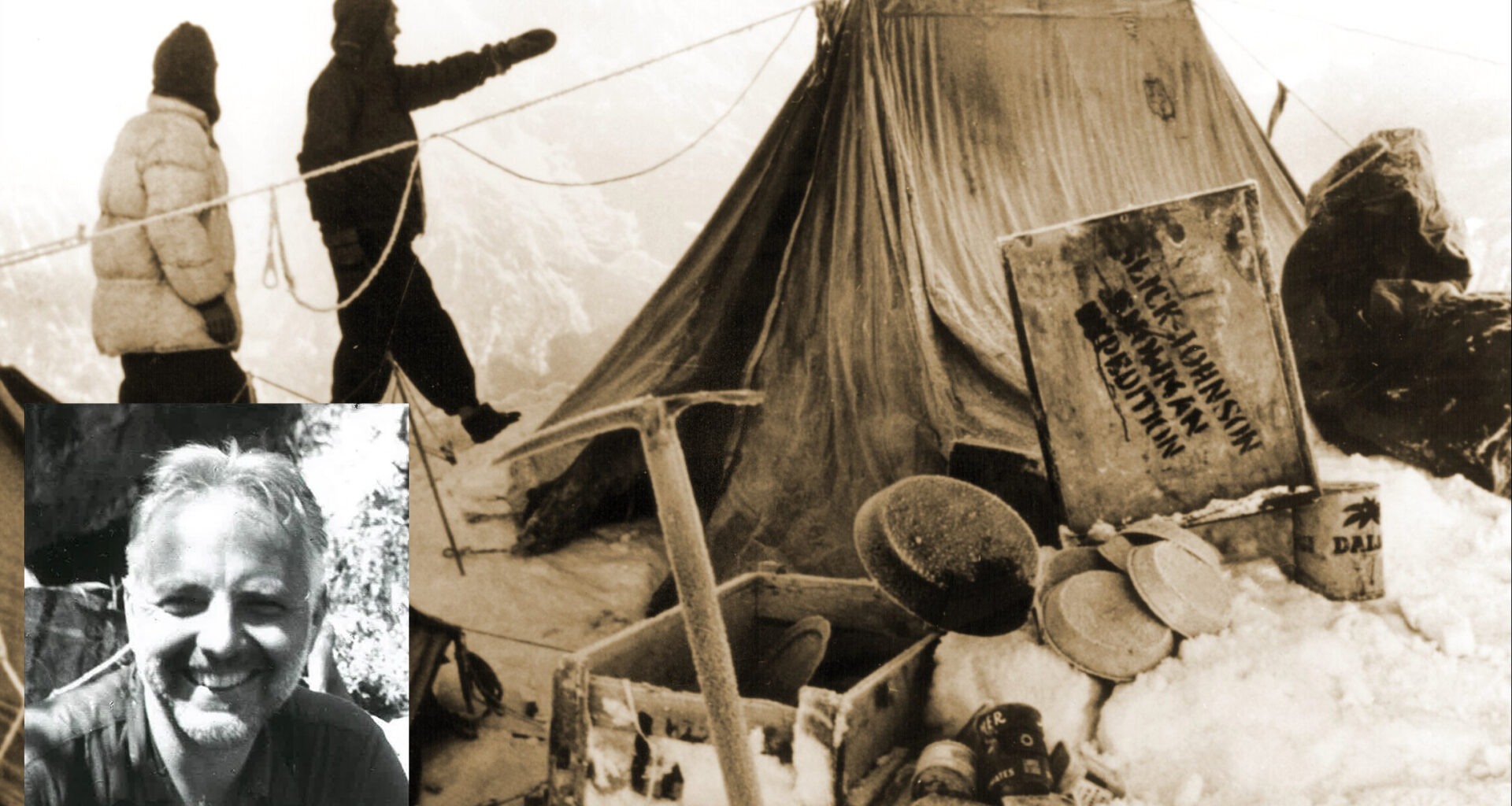

Explorers Club Flag Expedition “In the Footsteps of Tom Slick” in 2001. Credit: Courtesy / Catherine Nixon Cooke

Explorers Club Flag Expedition “In the Footsteps of Tom Slick” in 2001. Credit: Courtesy / Catherine Nixon Cooke

To SwRI CEO and President Adam Hamilton, the Yeti represents a sense of lightness and curiosity that Slick brought to science — what he describes as boundless childlike curiosity, open mindedness and a willingness to fail.

“[Slick] was curious,” Hamilton said. “And curiosity is a critical element of scientific and technical advancement. If we weren’t curious about things, we wouldn’t be motivated to do a lot of the kind of work that we do.”

And, he added, the yeti brings a sense of playfulness to campus. “We do hard technical work all day,” Hamilton said. “You do have to have some distractions.”

Aside from his work, Slick married twice and left behind four children.

His niece followed his footsteps by joining the Explorer’s Club — a professional society with the goal of promoting scientific exploration and field study. In 2001, Cooke completed an expedition to the Himalayan Mountains carrying the organization’s flag in the footsteps of her uncle.

“He managed to achieve more than most do in a full lifetime,” Cooke said of Slick. “But I think of him as a brilliant star that zoomed across our universe too briefly.”

Are you doing your part?

You’ve read unlimited of unlimited articles this month. That’s right — we’re committed to providing free, fair journalism for all.

But without donor support, our nonprofit newsroom can’t do its job to inform and empower your community.

Are you in? Your donation of any amount will help keep articles like this one accessible to all San Antonians.