Overview:

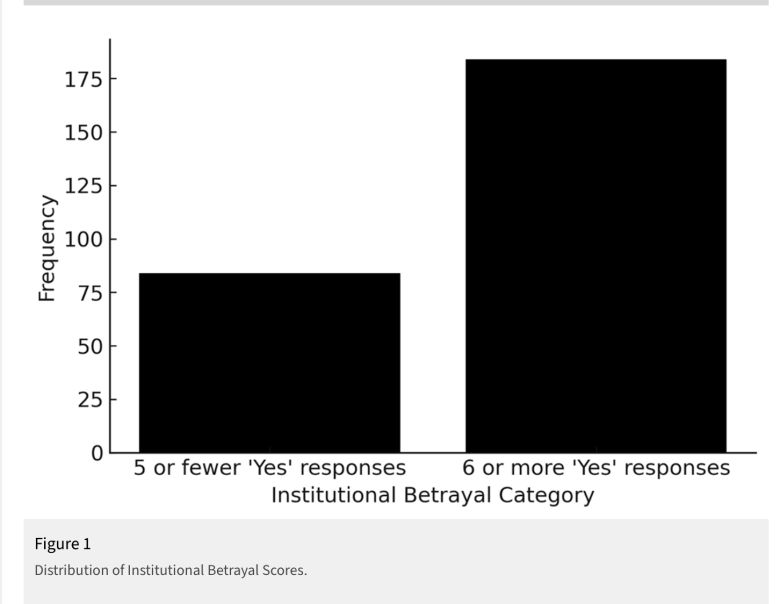

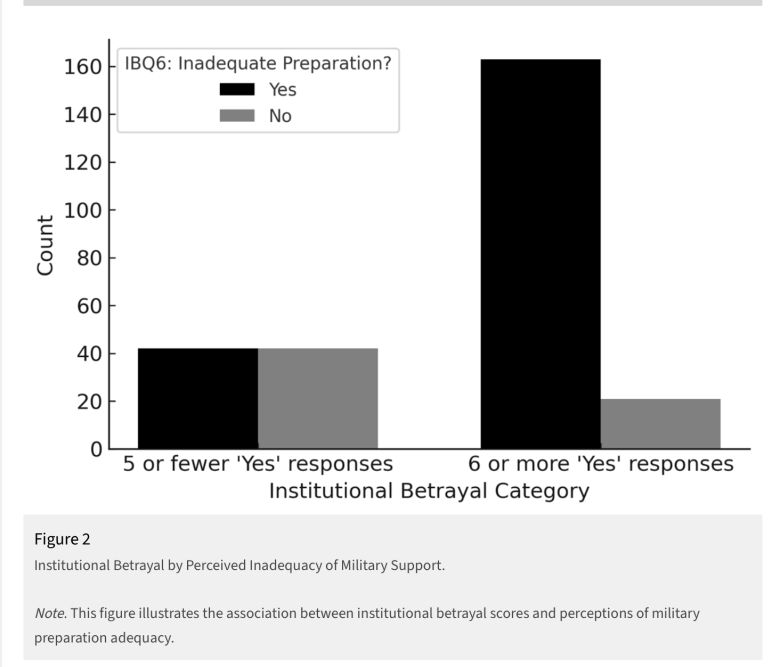

A study by the Journal of Veterans Studies has found that institutional betrayal is a systemic issue that affects many Black and Brown veterans who struggle to find stable jobs, affordable housing, and quality health care after military service. The study found that 79.5% of veterans who felt unprepared for civilian life reported six or more betrayal indicators, and that veterans who felt abandoned during their transition out of service experienced deep feelings of betrayal and distrust toward the military institution. The study suggests that preparation, connection, and community make all the difference in reducing feelings of betrayal and distrust.

The Quiet Battle After Service

For many South Dallas veterans, the end of military service doesn’t bring peace—it brings a new kind of fight. The struggle to find stable jobs, affordable housing, and quality health care often feels like a battle all over again.

A new study from the Journal of Veterans Studies is putting a name to something many Black and Brown veterans already know too well: institutional betrayal. It’s the sense of being abandoned or dismissed by the very systems meant to protect them.

Researchers found that veterans who felt unprepared for civilian life were far more likely to experience deep feelings of betrayal and distrust toward the military institution. Nearly 80% of those who said their transition support was inadequate also reported signs of institutional betrayal.

That means this isn’t just about poor planning or paperwork, it’s about broken trust.

What “Institutional Betrayal” Really Means

The idea comes from Betrayal Trauma Theory, which explains how trauma hits harder when it’s caused by a trusted person or system. We expect strangers to hurt us, but not our families, churches, hospitals, or in this case, the military.

In the military context, institutional betrayal shows up when veterans feel abandoned during their transition out of service, when promises of “we take care of our own” turn into silence and red tape.

This can look like:

- Getting little or no help finding a job.

- Being denied or delayed in mental health services.

- Feeling like concerns about trauma, harassment, or injury were brushed aside.

For veterans of color and women, these feelings often cut even deeper.

The Numbers Behind the Pain

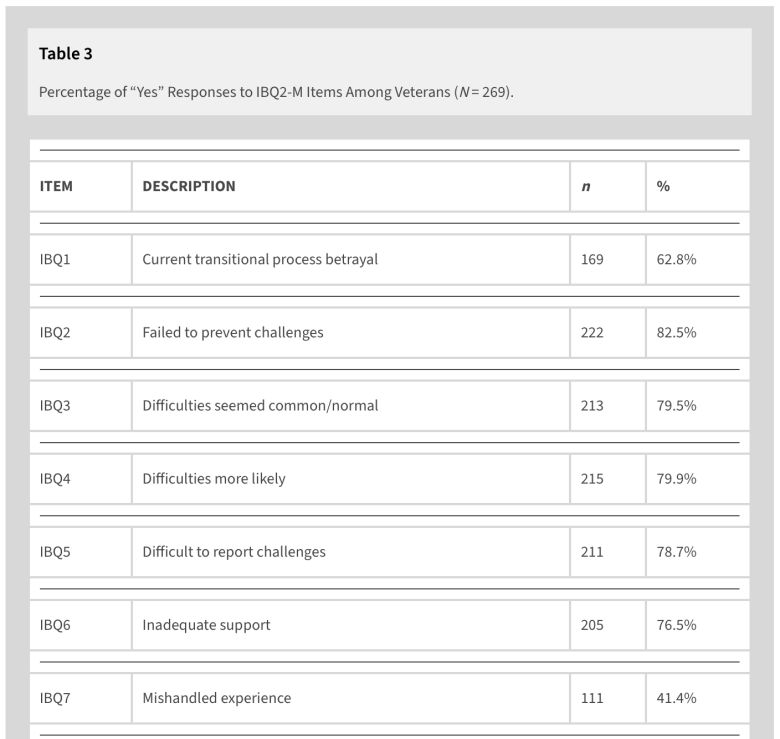

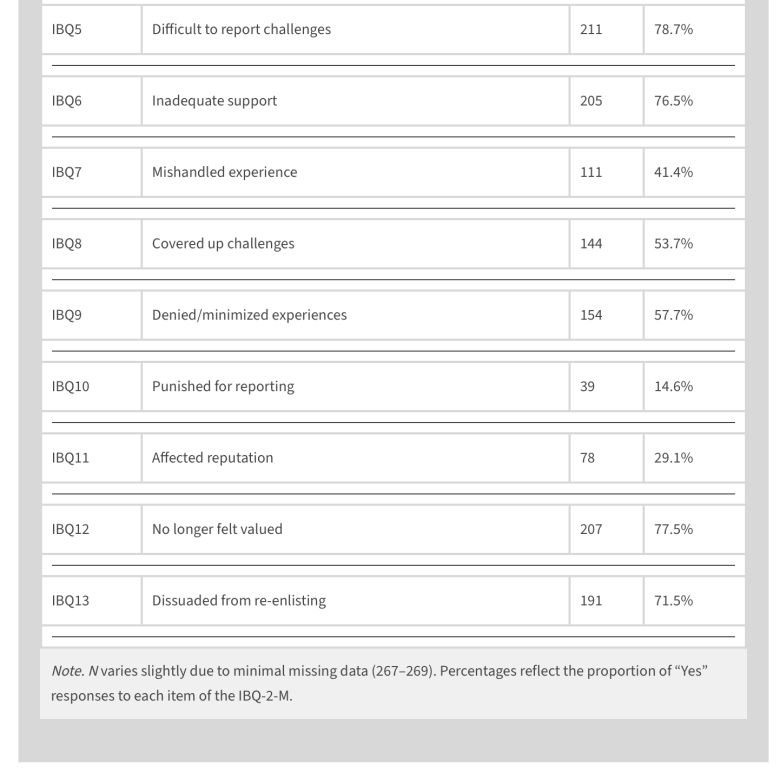

The study surveyed 269 U.S. veterans using a tool called the Institutional Betrayal Questionnaire (Military Version, supported by the evidence of Freyd and Smith).

The results were striking:

- 79.5% of veterans who felt unprepared for civilian life reported six or more betrayal indicators.

- Only 33.3% of those who felt prepared reported the same.

- Demographics like race, gender, and military branch didn’t change the results. This means institutional betrayal is widespread and systemic.

But the research also reveals an important truth: when veterans do feel supported, their sense of betrayal drops dramatically. Preparation, connection, and community make all the difference.

Why Black and Brown Veterans Feel It Harder

Even though the study didn’t find racial differences in betrayal rates, the context matters. For Black and Brown veterans, the feeling of being failed by a system isn’t new, it’s familiar.

Many return home to the same inequities they left behind: limited access to mental health care, economic barriers, and institutional bias. Nationally, veterans of color face higher rates of unemployment, homelessness, and untreated PTSD than their white counterparts.

Here in Dallas, the disparities are visible. According to local VA data, Black veterans make up a disproportionate number of those seeking care for PTSD and depression, and many report difficulty trusting the VA after previous negative experiences.

It can be deduced that coming from a community that’s been historically overlooked, the sense of betrayal hits differently. In some aspects, veterans of color may feel the system is failing them on purpose.

Trust Lost

The study also revealed that many veterans didn’t initially label their experience as “betrayal.” They just knew something felt wrong. But after reflecting on their struggles. After feeling dismissed, unsupported, or unprepared, they recognized the pattern.

That silence says a lot. Veterans are trained to endure hardship and not complain. But beneath the surface, the emotional toll of institutional neglect builds up.

Even recruiting participants for the study was hard. Over 100 veterans dropped out once they read that the research was about betrayal. Some worried it was linked to the VA or military and didn’t want to be identified. Only after a trusted veteran podcast endorsed the study did participation rise.

That hesitation mirrors what’s happening in our communities. Mistrust runs deep; not just toward the VA, but toward public health institutions and local government systems too.

The Transition Trap

Every year, around 200,000 service members leave the military and begin their transition to civilian life. The military offers programs like the Transition Assistance Program (TAP), but only about 57% of veterans in the study said they actually used it—and one in three said they received no transition help at all.

For some, the lack of preparation feels like abandonment. For others, it feels like proof that their service was disposable.

RELATED: Our Fight At Home: From the Fleet to a Firm Foundation

This emotional and logistical free fall often leads to mental health issues: depression, anxiety, substance use, and even suicide. When that happens, the gap between “thank you for your service” and real support becomes impossible to ignore.

A Path Forward: Healing Institutional Wounds

The Journal of Veterans Studies article doesn’t just call out the problem, it points to solutions that could make a real difference, especially for veterans in communities like South Dallas.

1. Betrayal-Informed Care

Therapists and counselors who work with veterans should help them name what they’ve experienced not just PTSD or depression, but the pain of institutional betrayal. Recognizing that wound can help reduce shame and rebuild trust.

2. Group Therapy & Peer Support

Veterans often heal better together. Group sessions focused on betrayal and trust repair can help veterans realize they’re not alone and create space for solidarity and validation.

3. Reform Transition Programs

The military’s separation process should go beyond résumé workshops. Veterans need ongoing check-ins at 3, 6, and 12 months post-discharge, with special outreach for those from marginalized backgrounds.

4. Community-Led Partnerships

Local clinics, nonprofits, and churches in our South Dallas community can play a critical role in bridging the gap between federal systems and veterans on the ground. Trust starts local.

5. Accountability at the Top

Military leadership should be evaluated not just on readiness and combat performance, but on how well they prepare their troops for life after service. Transition support isn’t a courtesy, it’s a moral duty.

Closing the Gap

The study makes one thing clear: veterans’ struggles after service aren’t just personal, they’re structural. Institutional betrayal is not about one bad policy or one missed appointment. It’s about a pattern of neglect that turns sacrifice into silence.

For South Dallas’ veterans, especially those from communities of color, the promise of care after service must become more than rhetoric.

We owe our veterans not just medals or ceremonies, but meaningful, consistent support that restores trust in the systems built to serve them.

Related