Water flow measures are taken at Hanawi Stream in East Maui. A protracted drought is leaving once-flourishing streams in the region at historic low levels. PC: Hawaiʻi Commission on Water Resource Management

Water flow measures are taken at Hanawi Stream in East Maui. A protracted drought is leaving once-flourishing streams in the region at historic low levels. PC: Hawaiʻi Commission on Water Resource Management

Alarmed about a severe and protracted drought, state and Maui County water officials are reporting historic low flows in East Maui streams and weighing their options to maintain water supply to residents and farmers. The dry weather impacts are being felt in a region popular among visitors for its Road to Hāna, which traverses Maui’s normally lush landscape, a northeast region often referred to as the “Garden of Eden.”

The Oct. 28 briefing for members of the Hawaiʻi Commission on Water Resource Management raised urgent concerns about the source of East Maui’s and — by extension — Upcountry’s drinking water supply, prompting state water officials to consider revising in-stream flow standards as an emergency measure.

The extreme dry conditions, detailed in a presentation by the commission’s Stream Protection and Management Branch, revealed that key stream systems are experiencing their lowest flows on record, straining the Maui County Department of Water Supply’s ability to serve Upcountry residents and leaving Mahi Pono with no surface water for Central Maui farming for the last two months. That has forced the island’s largest farm business — which has been striving to transform former sugarcane lands into diversified agriculture — to rely on pumping Central Maui groundwater for crop irrigation.

Upcountry faces crisis as flows drop

The drought’s severity impacted Upcountry residents earlier this year when the Maui County Department of Water Supply imposed Stage 3 drought restrictions, which limit water use to public health and safety only. This came after a critical intake at the Kamole Weir Water Treatment Plant in Hāliʻimaile ran at only two-thirds’ capacity, resulting in a loss of “over a million gallons a day” of pumping capacity for Upcountry, according to Deputy Water Director James ‘Kimo’ Landgraf.

Maui County Department of Water Supply Deputy Director Deputy Water Director James ‘Kimo’ Landgraf (lower right) appears last week before the Hawai‘i Commission on Water Resource Management. PC: YouTube

Maui County Department of Water Supply Deputy Director Deputy Water Director James ‘Kimo’ Landgraf (lower right) appears last week before the Hawai‘i Commission on Water Resource Management. PC: YouTube

“We have never seen it as dry as it has been for 30 years,” he told commissioners last week. He added that the situation was “scary.”

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW AD

“I would get up every morning and look at the mountain and see if it was raining,” he said.

Following a period of rain rain on Oct. 17 and into the weekend, the Water Department was able to reduce restrictions to Stage 2 on the day of the commission meeting (Oct. 28) but noted the County would return to Stage 3 immediately if conditions deteriorated.

Ayron Strauch of the commission’s Stream Protection and Management Branch described the sustained lack of water in East Maui as an “extreme drought,” following an “extremely dry” season in 2025.

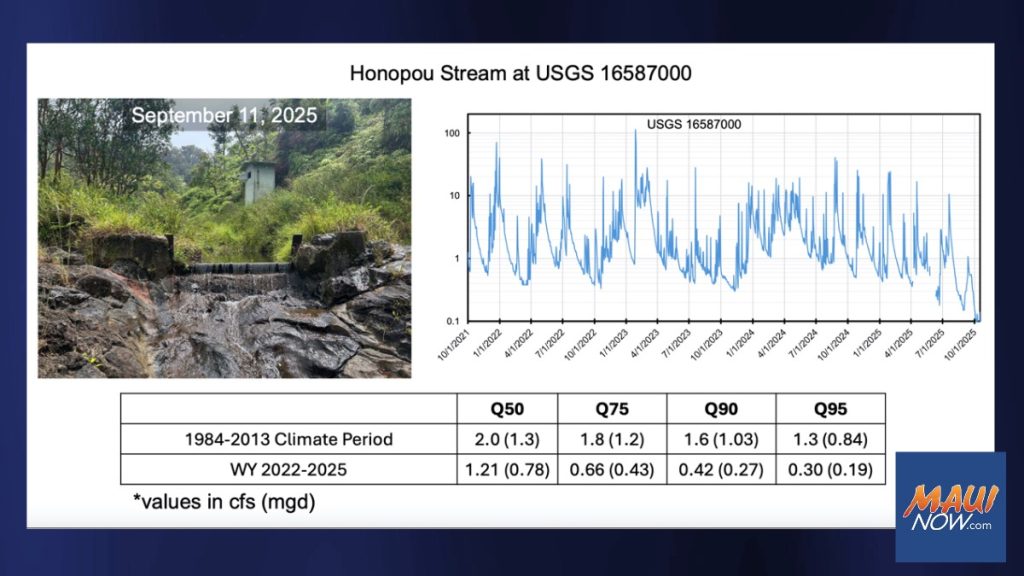

Data from the Honopou Stream water flow gauge, which has operated since the 1920s, showed the stream’s flow was less than the very low Q95 flow (the flow equaled or exceeded 95% of the time) for 150 out of 365 days in 2025.

A slide from a presentation by the Hawaiʻi Commission on Water Resource Management’s Stream Protection and Management Branch illustrates extreme low water flow conditions at Honopou Stream. PC: CWRM

A slide from a presentation by the Hawaiʻi Commission on Water Resource Management’s Stream Protection and Management Branch illustrates extreme low water flow conditions at Honopou Stream. PC: CWRM

“So that is as bad as it has ever been,” Strauch said.

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW AD

He presented data showing the stream’s dependable base flow (Q95) has dropped from 1.3 cubic feet per second in a previous period of record (1984 to 2013) to just 0.3 cfs in the most recent three years. He noted that from August through October, flows dropped as low as 0.1 to 0.18 cfs, which are “all-time record low flows.”

The dry conditions extend to the Upper Kula water system, where the US Geological Survey gauge at the 4,800-foot level of Haleakalā was recording zero flow for much of the past few months. “Historically, this fed about half a million gallons per day to the Olinda water treatment facility,” Strauch said.

Controversial emergency plan for stream flows

To secure the domestic water supply during extreme drought, Strauch suggested the commission pre-identify an action plan that could involve modifying in-stream flow standards — the minimum flows required to remain in the stream — as an emergency measure.

He noted that staff analysis of certain streams, like Hanawī, that gain water from groundwater below their diversions, suggests that even partially restored streams show comparable or greater abundance of native aquatic species.

A long-term trend of shifting prevailing winds from northeast to east is leaving once abundantly flowing East Maui streams and ditches with what state water officials are now reporting as historically low flows of water. Water in this irrigation ditch alongside Hāna Highway was well below its highest levels on June 16. File photo. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

A long-term trend of shifting prevailing winds from northeast to east is leaving once abundantly flowing East Maui streams and ditches with what state water officials are now reporting as historically low flows of water. Water in this irrigation ditch alongside Hāna Highway was well below its highest levels on June 16. File photo. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

“The story is, basically we don’t see any added benefit of full restoration” in some streams, Strauch said, suggesting that a more flexible in-stream flow standard could be a minimal-impact tool to protect drinking water.

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW AD

He identified Hanawī, Kapa‘ula, Pa‘akea and Kopili‘ula streams as candidates for potential temporary withdrawal modifications, but specified “not streams designated as kalo-producing or community use streams.”

The suggestion drew immediate opposition from community groups.

Jonathan Likeke Scheuer, chair and Hawaiian Homes Commission representative to the East Maui Regional Community Board, said the timing was “bad.” He pointed out that while some stream segments are restored, many community members “are still seeing water exported” to Central Maui while their streams are “really low.”

ARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW ADARTICLE CONTINUES BELOW AD

He added: “And now you’re hearing, ‘Oh, and CWRM is thinking about taking even more.’”

Commission Chair Dawn Chang clarified the commission was not proposing any immediate action, saying, “we are extremely concerned about the drought conditions… So look at all the tools, but also take into consideration the community’s concerns as well.”

Alarm over agricultural groundwater pumping

The drought has severely impacted agricultural water users, leading to concerns about groundwater resources. Under an agreement, East Maui Irrigation is prioritizing the Department of Water Supply’s needs for domestic use, resulting in Mahi Pono receiving no surface water since Aug. 28, according to Strauch.

Instead, the company has been irrigating crops with groundwater from the Central Maui ʻĪao aquifer system. Strauch reported Mahi Pono has been “ramping up groundwater production” to sustain its operations.

Mahi Pono watermelon.

Mahi Pono watermelon.

Scheuer expressed alarm about Mahi Pono’s water withdrawals from the Kahului and Pāʻia aquifers, which he noted were exceeding sustainable yield limits. (Sustainable yield refers to the maximum amount of water that can be safely pumped out of an underground source over time.) He reported pumping up to 13 million gallons per day from the Kahului aquifer, which has a sustainable yield of 1 mgd, and up to 25 mgd from Pāʻia, with a sustainable yield of 7 mgd.

“You’re like hundreds of percent over sustainable yield,” Scheuer said, urging the commission to get an immediate update on the Central Maui groundwater situation. Over-pumping an island aquifer risks saltwater intrusion, which can contaminate the well water permanently.

Department of Water Supply works to increase capacity

Maui County Water Director John Stufflebean told commissioners that his department is working to improve water supplies.

Maui County Department of Water Supply Director John Stufflebean (lower right) explains plans to increase domestic water supply for Upcountry customers before the Hawai‘i Commission on Water Resource Management. PC: YouTube

Maui County Department of Water Supply Director John Stufflebean (lower right) explains plans to increase domestic water supply for Upcountry customers before the Hawai‘i Commission on Water Resource Management. PC: YouTube

One priority step has been to increase capacity at the Kamole Water Treatment Plant by replacing two-decade-old filters with new technology.

“With those new filters, we will be able to take more water at the Kamole (Weir) plant,” Stufflebean said, adding the department will be “requesting… additional water allocations from the Wailoa Ditch because the plant will be able to handle additional water.”

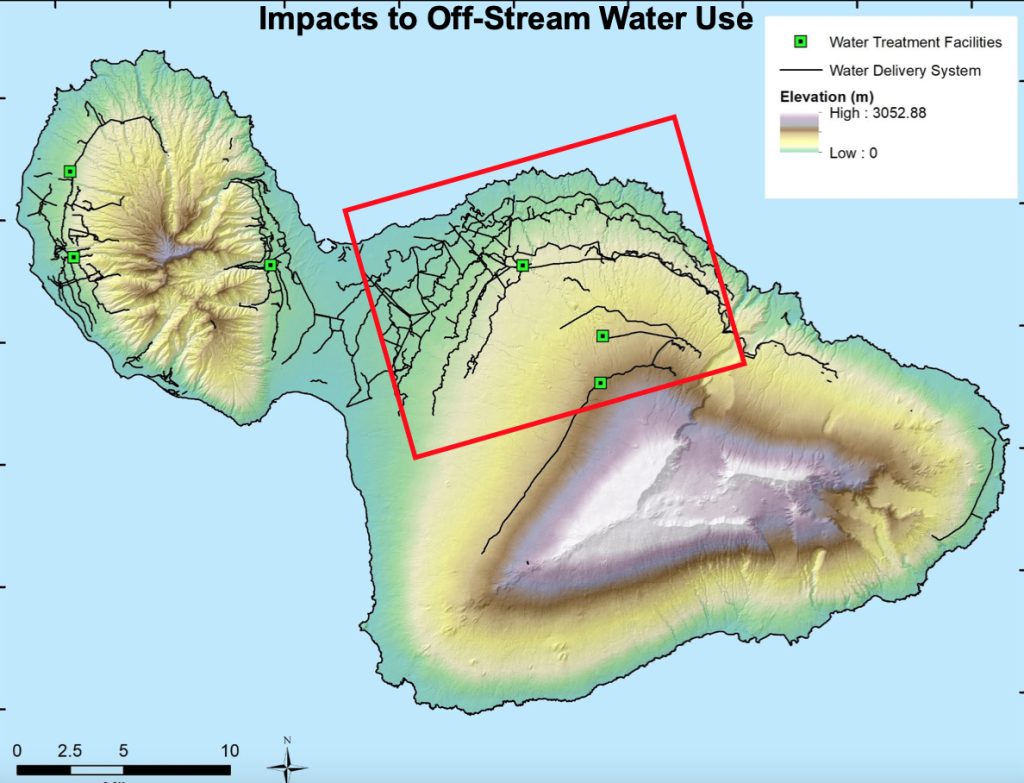

A map shows the current location of water treatment plants and water delivery systems, largely fanned out in northeast Maui, not in East Maui where prevailing trade winds have been shifting over the past few decades. PC: CWRM

A map shows the current location of water treatment plants and water delivery systems, largely fanned out in northeast Maui, not in East Maui where prevailing trade winds have been shifting over the past few decades. PC: CWRM

The Water Department is also in the design phase for two reservoirs at the Kamole Treatment Plant that will — together — add storage capacity of 140 million gallons. The reservoirs’ estimated cost is $25 million.

The County is seeking federal funding for the project, which Stufflebean called the department’s top priority for federal funding.

The County also reported using two Hamakuapoko wells for two months, which “really saved us” during the dry period, Stufflebean said. The County also is looking at purchasing or leasing private wells in the region and drilling new county wells.

Climate context: Shifting winds

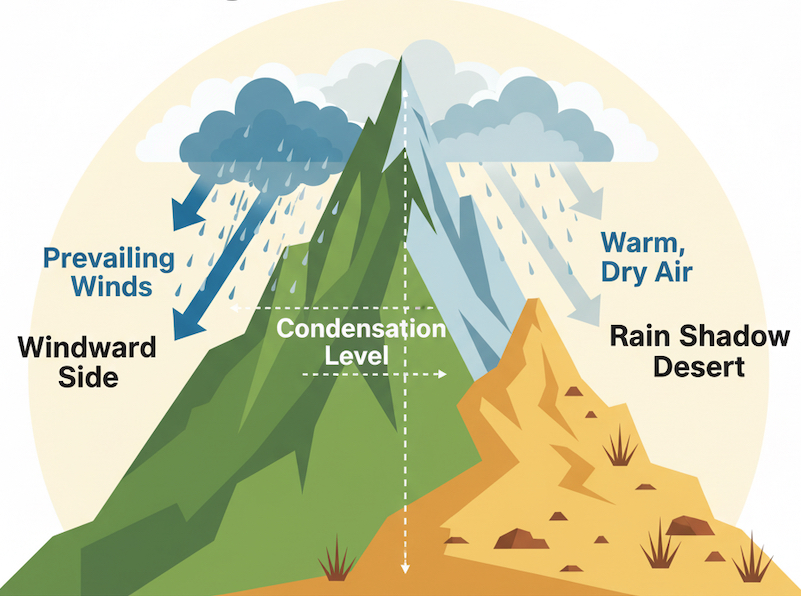

A graphic shows “orographic” precipitation. When winds carrying moisture-laden air encounter mountains and move up and over them, cooler temperatures cause water vapor to condense and produce rain. A shift in prevailing wind patterns, even slightly from the northeast to east, means that rain falls away from long-established water catchment and treatment systems on Maui. Simply put, the rain spigot has moved but the buckets have not.

A graphic shows “orographic” precipitation. When winds carrying moisture-laden air encounter mountains and move up and over them, cooler temperatures cause water vapor to condense and produce rain. A shift in prevailing wind patterns, even slightly from the northeast to east, means that rain falls away from long-established water catchment and treatment systems on Maui. Simply put, the rain spigot has moved but the buckets have not.

The root cause of the ongoing dry conditions is a decades-long downward trend of the prevailing northeasterly trade winds. Historically, those winds have brought moisture-laden air over the islands, generating orographic rainfall. As the air moves upward over mountain areas, it cools and water vapor condenses into rain.

Climate studies from the 1970s to 2010s have shown a significant shift to more easterly and variable winds. (To see a summary of a 2012 University of Hawai‘i study, visit here.) The problem for East Maui is that this has effectively moved the “rainfall spigot” to the east, away from the northeast areas where man-made ditches were dug a century ago to capture streamwater.