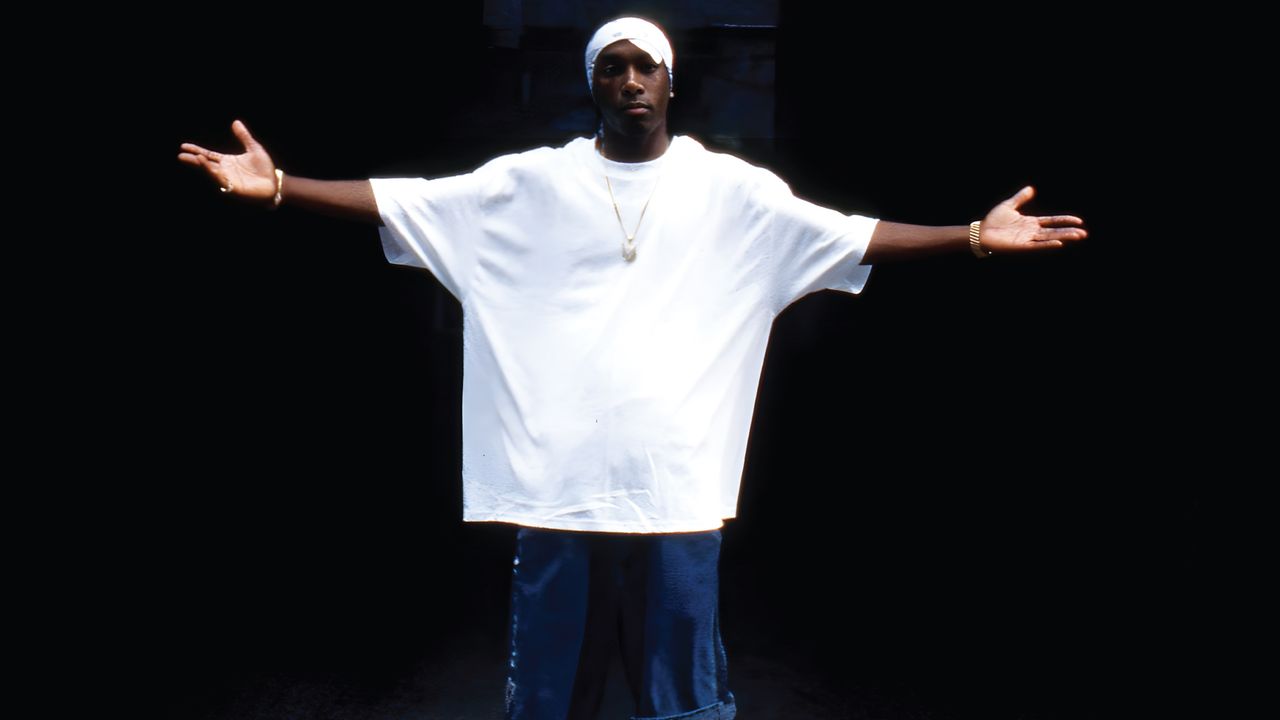

You could hear in his voice that Big L knew he was destined to become a legend. Beneath the hunger, the anger, and the near-frantic aggression was the unshakeable confidence of the kind of person who slides on sunglasses while strolling away from an explosion. L had a preternatural talent, his slick, smarmy flow sluicing over beats, each verse a knotted rope of multisyllabic rhyme schemes and disturbingly clever punchlines. He was a heat-seeking missile, a force that left craters in freestyle sessions and struck fear in other rappers’ hearts. Nas is on record saying as much: “Big L scared me to death. When I heard that on tape, I was scared to death. I was like, ‘There’s no way I can compete if this is what I gotta compete with.’”

Born Lamont Coleman in 1974, the young Harlem MC rose quickly and burned bright. He joined Diggin’ in the Crates in 1991 as a teenager, signed with Columbia in ’93, and released his first album, Lifestyles Ov Da Poor and Dangerous, to critical acclaim in 1995. L was on the cusp of becoming New York rap royalty, getting cosigns from and trading verses with Jay-Z, touring Europe with O.C., and earning the adoration of nearly every DJ, radio personality, and culture carrier in the city. As the hype around his nascent career grew, L started a label, Flamboyant Entertainment, and began work on his second album, The Big Picture. There was talk of him signing to Roc-A-Fella. All signs pointed to a lengthy, storied career. Then, on February 18, 1999, L was killed in a drive-by shooting near 139th Street and Lenox Avenue, the area he referred to as “The Danger Zone.” He was 24.

The posthumous record is a tricky, seldom successful endeavor. Big L’s first posthumous record, The Big Picture, was a rare exception, benefitting from the fact that he’d been working on it for two years before he passed. It was polished and nearly seamless; the guest appearances felt natural, the tone consistent. But L was young and didn’t leave an enormous vault of material. There’s a trove of his radio freestyles, but almost all have been circulating on Soulseek and YouTube for at least two decades. Whatever was left of his archive was picked over, remixed, or cut-and-pasted into “new” songs on 2010’s 139 & Lenox and 2011’s The Danger Zone. Harlem’s Finest: Return of the King, Big L’s fourth posthumous record, and the latest entry in Mass Appeal’s Legend Has It series, shows that the well is running dry. It’s a tonally confusing collection that sometimes scans as reverent homage but often comes across as hollow and perfunctory.