Elenore Sturko, the independent MLA for the riding of Surrey-Cloverdale, is calling on Premier David Eby and the B.C. NDP-led provincial government to publicly disclose all lawsuits filed by First Nations asserting Aboriginal title over land in the province — particularly where those claims may overlap with existing private property.

Sturko said British Columbians deserve to know when court cases could affect their property rights, warning that several ongoing Aboriginal title claims have “potential to impact entire communities.”

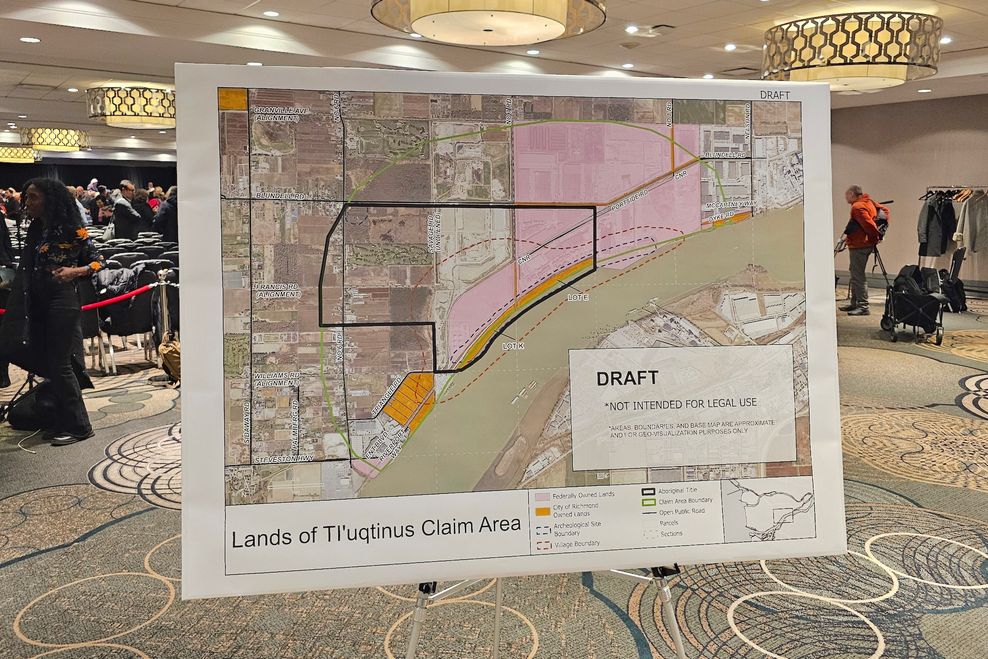

According to her, the recent decision by a B.C. judge that granted Aboriginal title to the Cowichan Tribes in southeast Richmond is “just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to claims of Aboriginal title in this province.” There are concerns that the case sets a precedent for Aboriginal title trumping over fee simple title, which is the overwhelmingly private property typology in Canada.

All three levels of government are appealing the ruling that sided with the Cowichan Tribes, but Sturko warns that concerning precedents have already been set by the provincial government in how their lawyers handled the case in court, as well as the granting of Aboriginal title over private property across Haida Gwaii.

“The government has utterly failed to act in its basic duty to notify British Columbians of litigation that directly impacts their rights,” said Sturko in a statement on Thursday.

Such claims can slowly snail through the legal system for years, perhaps even a decade a more. That was the case for the Cowichan Tribes’ claim, which first began a decade ago, with the court trial itself starting in September 2019 and spanning a total of 513 court hearings and trial days — making it the longest in Canadian history.

However, none of the private property owners in the Richmond claim area were formally informed of the matter until earlier this fall — weeks after the judge made its decision siding with the First Nation that extended to both public and private property. The governments involved in the case have blamed a judge’s early decision not to inform private property owners over concerns that their participation in the litigation could overwhelm the case.

Claiming the entire area in and around Kamloops, and beyond

As a major example of the high degree of secrecy and large scope of the claims that are working through the judicial system behind the scenes, Sturko shared that the Secwepemc First Nation first filed a Notice of Civil Claim in September 2015 seeking a declaration of Aboriginal title to all or part of their traditional territories in the B.C. Interior. This included the entirety of the City of Kamloops, a number of other municipalities, Sun Peaks Resort, roads, railways, and privately owned tenures of many types — including fee simple grants, mineral tenures, and many other Crown-granted interests.

The municipal jurisdiction of the City of Kamloops alone spans nearly 300 sq. km. — more than two and a half times the size of the City of Vancouver — and is home to over 100,000 people.

In the filing, the Secwepemc First Nation states they are pursuing Aboriginal title due in part to prevent the operations of the Ajax copper and gold mine near Kamloops, alleging it would violate their Indigenous rights, desecrate “sacred” lands, and cause environmental harm.

They assert their traditional territory covers a much larger area — far beyond their claim area — of about 180,000 sq. km, which is nearly 20 per cent of the entire land area of B.C.

The Secwepemc First Nation asserts this area is roughly framed by “Ashcroft on the Thompson River and an area west of the Fraser River to Quesnel in the north, then east to Windemere, then along the northern part of the Arrow Lakes to the Salmon River and Enderby, and then to the Logan Lake Plateau south of Kamloops and back to Ashcroft.” However, there are likely substantial overlaps with the traditional territories deemed by other First Nations in this area.

“The Secwepemc reserve the right to claim Aboriginal rights and title to the whole of Secwepemc Traditional Territory in the future,” reads the Notice of Claim.

Sun Peaks Resort. (Harry Beugelink/Shutterstock)

However, in January 2016, the provincial government’s lawyers formally denied nearly all of the allegations made by the Secwepemc First Nation, and asked the court to dismiss the claim as it amounted to an “abuse of process.”

“This Claim appears to have been filed in response to a particular project, in this case, the proposed copper and gold mine, known as the Ajax Project. The Project Area is located largely on privately held fee simple lands, which were lawfully granted,” wrote B.C.’s lawyers in their response.

The response emphasizes that the disputed lands are not only Crown property but also include “privately owned tenures of many types.” The provincial government holds “underlying title to the lands and minerals at issue” and has the constitutional authority to manage them.

While the provincial government admits it has a legal obligation to consult and, in some circumstances, accommodate Indigenous peoples over “unproven claims of Aboriginal rights and title,” it insists that formal recognition of the Secwepemc First Nation’s Aboriginal title has not been established.

“Aboriginal rights and title exist in British Columbia,” the Province acknowledges, “but the Plaintiffs’ allegations… do not sufficiently or clearly address [the legal] requirements and do not permit the Province to respond to the claims as to the locations where Aboriginal rights are exercised within the Territory.”

At the time, the provincial government also questioned the historical basis for the Secwepemc First Nation’s Aboriginal title across such a vast area.

“Aboriginal people speaking the Secwepemc language lived in bands which were comprised of loosely knit networks of extended families and households which were not politically unified or organized,” states the response, adding that their ancestors “opportunistically hunted, fished and gathered for sustenance” and did not have “exclusive occupation” of the entire territory.

Similar arguments were made by the Musqueam Indian Band and Tsawwassen First Nation, who were the defendants in the Cowichan Tribes case in Richmond. Both First Nations disputed the existence and legitimacy of the Vancouver Island-based First Nation, which asserted they had a summertime village on the Fraser River in southeast Richmond.

In one of its most direct statements, the Province’s lawyers argued that even if Secwepemc First Nation’s Aboriginal title once existed, “the co-existence of that title is inconsistent with and displaced by the estate of any private land owner and Crown-granted mineral claim holder.” It emphasizes that the existing grants to private owners and mining companies were “lawfully granted and remain valid to their full force and effect.”

The provincial government also claims any infringement of Indigenous rights was justified by “pressing and substantial objectives” for the collective good of B.C. society as a whole, including direct and indirect benefits for First Nations.

“The Province’s actions since 1871 as government and owner of the underlying title to the lands and resources of the Territory have been for the benefit of the people of British Columbia, including the Plaintiffs,” wrote the Province’s lawyers.

“In particular, British Columbia has pursued policies and undertaken actions throughout the Province, including the Territory, which have, directly or indirectly, developed agriculture, forestry, mining, the economy generally, regulated wildlife harvesting, protected the environment and endangered species, established and maintained public services including a justice system, land and sea transportation, health care, education and social welfare for the benefit of the people of British Columbia, including the Plaintiffs.”

“From time to time, the Plaintiffs, their ancestors and those they represent have enjoyed the benefit of those actions, policies and services, the cumulative effect of which has been to justify any infringement of established Aboriginal rights and title.”

These were the arguments made by the Province’s lawyers at a time when the B.C. Liberals governed the provincial government.

This case, first filed in court nearly a decade ago, is still ongoing, with Sturko warning there could be numerous other similar cases that have yet to be unearthed, and urging Premier Eby to proactively make these cases public.

In recent months, the B.C. NDP-led provincial government and the Government of Canada have been accused of a half-hearted defence in the court trial with the Cowichan Tribes by not making more explicit arguments and arguing for extinguishment — all part of their apparent approach to not impact the underpinnings of Indigenous reconciliation based on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the 2019-created provincial Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which are principle tenets of the current provincial government.

“While David Eby and his NDP government claim to be working to protect the interests of private property owners, they have failed egregiously to notify the public of claims filed against their private property and continue to work almost exclusively in secret, working up land-back agreements behind the backs of British Columbians. It’s time for the premier and his government to provide the transparency British Columbians deserve,” said Sturko.

Cowichan Tribes’ land claim area in southeast Richmond. (Kenneth Chan)

Earlier this week, when asked by media, Eby acknowledged the anxiety and stress that Richmond residential and business owners now face, and reiterated his government’s commitment to overturn the judge’s ruling in the forthcoming appeal process and seek a temporary stay of the legal implications of the court’s decision during the possible years-long appeal duration.

“The court assured us that they would make a decision that didn’t affect landowners in the claim area, so they didn’t have to be served — they didn’t have to be told about the case, that it was going ahead in court. Unfortunately, that obviously turned out not to be the case,” said Eby.

“Look, this is a hugely stressful time for these families that own these homes in the claim area, and rightly so. They didn’t know, many of them, about that this case was even happening, and then they learned from the mayor about potential implications for their title. And so, I just want to reassure those families and individuals that we’re doing all we can to seek a stay at the Court of Appeal to ensure those arguments are put forward at the Court of Appeal.”

The premier also encouraged affected homeowners to share any evidence of financing challenges or market impacts on their properties, saying such information would support the Province’s appeal.

B.C. will be “left behind, broke, divided, and wondering how we lost control of our own future”

These sentiments echo earlier debates over the B.C. NDP-led provincial government’s previously proposed controversial changes to the Land Act — with critics asserting this provides First Nations with veto powers over B.C.’s vast Crown lands.

Earlier this week, Premier Eby gathered with First Nations leaders across the province in Vancouver and signed the North Coast Protection Declaration, which the B.C. NDP-led provincial government heralds as an agreement that upholds the idea that environmental conservation, Indigenous rights objectives, and economic prosperity go hand-in-hand, including urging a federal ban on large crude-oil tanker ships since 2019 should be made permanent.

Independent MLA Jordan Kealy for the riding of Peace River North has sharply rebuked the declaration signed with “a handful of First Nations chiefs,” asserting that it is an affront to the democratic process, as no public consultation was performed, and it did not go through the legislature.

He asserts Alberta will simply work to push more of its oil exports south to the United States, with B.C. forfeiting the potential revenue and economic benefits. However, the declaration touts that this move protects the coastal and rainforest areas’ “multi-billion dollar, sustainable conservation economy that supports thousands of livelihoods in fisheries, tourism, renewable energy, and stewardship.”

Kealy suggests the provincial government should instead be working on a true economic partnership with First Nations, making them equal partners and owners in natural resource projects within a so-called “Northern Prosperity Corridor.”

“Our premier is helping Ottawa and a few coastal elites lock Alberta and Northern B.C. out of the ocean, block our export routes, and kill off future jobs, all while pretending it’s about ‘protection.’ Whose protection? Not ours. Not the working people in Fort St. John, Dawson Creek, Chetwynd, or any other northern communities who depend on energy, forestry, and resource jobs,” wrote Kealy in a statement.

“Eby and a few chiefs get to claim ‘shared governance’, but what they’re really doing is setting a dangerous precedent that will hurt the entire province, and country, moving forward. The fact that a few politicians and hereditary leaders can shut down national development without the consent of the people, is a completely wrong approach for the whole of the province and even Canada. It’s Canada’s coast too, not strictly B.C.’s.”

“This action shows an overpowering, heavy-handed approach that we do not need, and David Eby is using this power in a dangerous way. First Nations and non-Indigenous workers alike are going to pay the price. The North will see fewer pipelines, fewer tankers, fewer paycheques and more division. This isn’t leadership, it’s sabotage dressed up as reconciliation.”

Kealy further suggested that if the provincial government continues its current policy approach and style of governance, B.C. will be “left behind, broke, divided, and wondering how we lost control of our own future.”

Similar to the concerns raised by Sturko, Kealy says any new “declaration” in the future should go through the legislature and include public consultation.

But all signs point to the B.C. NDP-led provincial government continuing its approach of expanding its reconciliation measures in secrecy.

Just last month, the provincial government also proposed eliminating the referendum requirement in Vancouver for transferring parkland to First Nations — one of the several key conditions for the City of Vancouver to abolish the Vancouver Park Board, raising questions about democratic safeguards around land transfers.

As well, the provincial government recently proposed legislation to enable municipal governments to hold secret meetings and negotiations with First Nations for confidential matters and cultural sensitivity purposes.