There are about 10,000 acres of abandoned buildings and 45,000 acres of vacant paved lots in Houston, which drives up intense heat in a city that has long grappled with the reputation — and economic impact — of its hot, humid climate.

Courtesy of Texas A&M College of Architecture

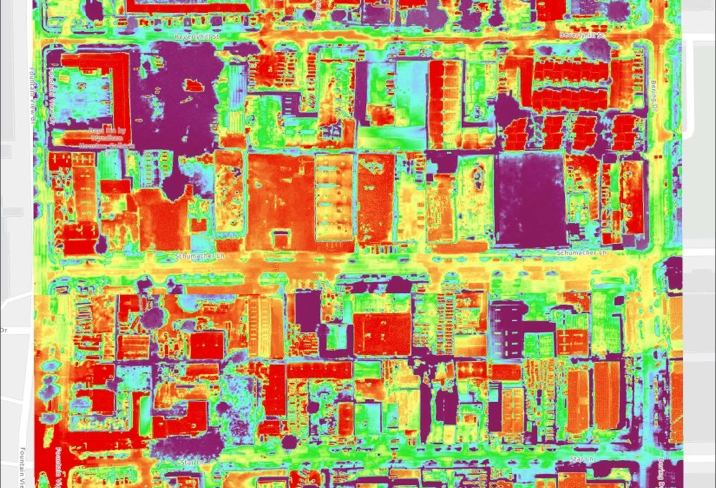

A thermal camera image of a commercial area in Houston, where red marks the hottest areas and purple the coolest.

The data comes from a study by Texas A&M University researcher Dingding Ren, which used drone images and NASA satellite data to find that abandoned buildings and concrete lots can raise land surface temperatures by as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

As climate change also drives up average temperatures — contributing to the past decade being the 10 warmest years on record — hot spots threaten residents with heat-related illnesses, hinder walkability and make public features like sidewalks dangerously hot.

High temperatures can also deter tourism and in-migration and reduce economic output.

The State of Downtown address given by Downtown Houston+ CEO Kristopher Larson last week focused on how the perception and treatment of Houston’s heat impacts the city. Past generations built massive, enclosed structures to avoid it, like the tunnels underneath Downtown office buildings.

“We set out to build a climate-controlled city, inclusive of elements that regarded the outdoors as a problem to be solved,” Larson said.

But now Houston’s leaders want to embrace its outdoor offerings and draw more people to street level. Residents and visitors flock to activated outdoor spaces, exemplified by the more than 3 million annual visits to Discovery Green.

“Houstonians want active green spaces, even if it’s hot out,” he said.

Vacant land and abandoned structures retain more heat during the daytime and experience higher temperatures at night because concrete absorbs heat and releases it slowly, according to the A&M study. But vacant lots with vegetation can help cool surrounding areas.

While they aren’t centered on the heat island effect, the city in recent years has had initiatives to demolish hundreds of dangerous, often vacant, buildings, and city leaders are looking to tear down three dilapidated Midtown-area buildings ahead of the FIFA World Cup next year.

There are more direct attempts to combat the effect of the built environment on the ambient temperature. The city plans to encourage building owners and developers to install heat-deterring features like light-colored roofs, using guidelines, incentives and/or mandates, according to the Resilient Houston plan.

The city is also working to combat the intensified heat that comes with a lack of vegetation.

Downtown Houston’s Public Realm Action Plan aims to draw more people to street level by creating more comfortable microclimates with added tree canopy and shade structures. This will soon transform McKinney, Texas and Preston streets, Larson said.

Resilient Houston, a strategy released in 2020, set a target of planting 4.6 million new native trees in the city by 2030. The initiative focuses on areas with the strongest urban heat island effects, air pollution, minimal tree cover and a high concentration of pedestrians and bicyclists.

Houston Mayor John Whitmire’s office didn’t immediately respond to a question about the city’s progress on its 4.6-million-tree planting initiative. But Trees For Houston, a nonprofit partner of the city, is on track to plant about 800,000 trees over the decade, Executive Director Barry Ward said.

“We saw that 4.6 million as a very laudable goal based on the best attainable data at that time,” Ward said.

But as Houston grows and new data comes out, like the Texas A&M study, goals need to be updated.

“More buildings, even while some go derelict, are being built in the suburbs,” Ward said. “The need is always increasing in the city. It’s never going down.”

Constantly increasing goals can seem unreachable, and urban tree mortality rates are high. Trees planted along Houston streets have an estimated 10% to 20% chance of living 50 years, Ward said. But all of that is reason to plant more trees, he said.

A group effort is needed to increase Houston’s greenery, Ward said. While Trees For Houston is the top nongovernmental tree planter in the city, many real estate developers also know the benefits of shade and work to retain existing trees or plant new ones in their projects.

“You take the onus off of the city,” Ward said. “That it is shared a little by the city, a little by the NGOs and a little by the developers. That, to us, is the kind of compromise that really moves the ball down the field.”