A remote cave system nestled along the border of Greece and Albania has revealed what may be the largest known spider colony on Earth—and possibly the largest web ever documented. The discovery, made by a team of European biologists, challenges long-held assumptions about arachnid behavior and adaptation, particularly among species once thought to be strictly solitary.

The cave, known as Sulfur Cave, houses a web complex sprawling over 100 square meters (approximately 1,076 square feet “100 m²”), constructed from thousands of interconnected funnel-shaped silken structures. What’s more, the structure is cohabited by more than 110,000 spiders from two distinct species—Tegenaria domestica and Prinerigone vagans—living together in apparent harmony.

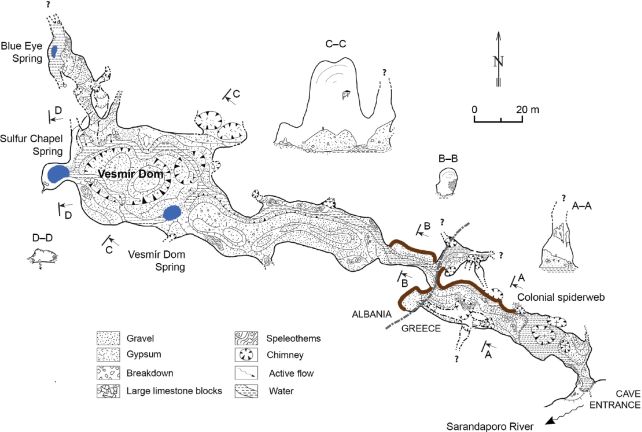

The layout of Sulfur Cave. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

The layout of Sulfur Cave. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

The finding, first reported in the peer-reviewed journal Subterranean Biology, documents not only the size of the structure but also a previously unknown form of facultative colonialism in two species historically observed in isolation. The team’s analysis suggests this behavior may have emerged in response to the cave’s uniquely sulfur-rich, lightless environment.

“We weren’t just observing webs—we were witnessing architecture on a different scale,” said István Urák, lead author and biologist at Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania. “This isn’t just a habitat. It’s an ecosystem engineered by spiders.”

A Thriving Ecosystem Built on Sulfur, Not Sunlight

Unlike most ecosystems on Earth, Sulfur Cave is sustained not by photosynthesis, but by chemoautotrophic bacteria that feed on hydrogen sulfide emitted from the cave’s geothermal springs. These microbes form dense biofilms, which serve as the base of an entirely subterranean food web.

The researchers conducted stable isotope analyses (δ¹³C and δ¹⁵N) to trace this food chain. Results confirmed that the spiders are primarily feeding on a native midge species (Tanytarsus albisutus), which in turn feeds on the microbial mats coating the cave walls. The entire ecosystem—from microbes to midges to spiders—functions independently of the sun.

Part of the giant colonial web in Sulfur Cave. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

Part of the giant colonial web in Sulfur Cave. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

“This is a classic chemoautotrophic system, akin to what we see in deep-sea vents,” said Serban Sarbu, a subterranean biologist and co-author of the study. “But what’s remarkable here is how surface-dwelling species have colonized and adapted to such a radically different biochemical environment.”

Both spider species typically inhabit human dwellings or forested areas, making their presence in Sulfur Cave—and their peaceful coexistence—all the more unexpected. DNA sequencing revealed these cave-dwelling populations are genetically distinct from their surface counterparts, showing no evidence of recent migration or interbreeding.

Colonial Behavior Defies Evolutionary Expectations

One of the most striking findings was the emergence of social web-building behavior in species long considered solitary. The funnel weaver T. domestica appears to be the primary architect of the web complex, while P. vagans occupies existing sections without contributing to construction.

Researchers expected interspecies predation, given that T. domestica is significantly larger than P. vagans. But field observations and spatial distribution analyses suggest the two species rarely interfere with one another. One hypothesis is that the perpetual darkness of the cave may suppress aggressive behaviors by limiting visual cues.

“There’s almost no precedence for this kind of cohabitation among spiders,” Urák noted. “It’s an extreme example of environmental pressure rewriting behavioral rules.”

A female of the species Tegenaria domestica in one of the web’s funnels. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

A female of the species Tegenaria domestica in one of the web’s funnels. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

The researchers also documented seasonal shifts in egg sac size among T. domestica, with larger clutches recorded during early summer. Gut microbiome analysis further showed that cave-dwelling spiders had significantly lower microbial diversity compared to individuals of the same species found near the cave entrance, a likely consequence of a more limited and homogeneous diet.

The Cave’s Complex Subterranean Network

Sulfur Cave is part of a larger limestone system that includes Atmos Cave and Turtle Cave. The network extends across national borders, with the entrance located in Greece and deeper corridors reaching into Albania. Water from sulfur-rich springs flows through the caves, eventually joining the Sarandaporo River.

The web and a swarm of midges. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

The web and a swarm of midges. (Urák et al., Subterr. Biol., 2025)

The cave’s inner walls are covered in slimy microbial films, forming a continuous substrate that supports a wide array of invertebrates including centipedes, pseudoscorpions, mites, and beetles. Notably, many of these species also appear to be genetically unique, suggesting a high degree of endemism driven by chemical isolation and evolutionary pressure.

What began as a casual discovery by recreational cavers in 2022 has quickly evolved into a significant biological investigation. The full scope of the ecosystem—both in terms of biodiversity and evolutionary adaptation—remains under study.