John Carpenter’s The Thing was technically a remake of a 1951 movie, which was itself an adaptation of a 1938 novella called Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell Jr. The original author’s work has actually been adapted on multiple occasions, although few would disagree that the 1982 version was by far the best of the lot. The Thing introduced a revolution in practical effects, spearheaded by Rob Bottin, a genius prosthetic makeup artist who designed the gruesome world that fans know and love today. However, the film wasn’t only about its visual aesthetic.

Carpenter’s association with Kurt Russell arguably peaked with The Thing, iconizing the character of R.J. MacReady. Despite maintaining his composure and common sense, however, MacReady was woefully ill-equipped to deal with the physical, psychological, and emotional havoc caused by the so-called thing. Taking a cue from Jaws, which elevated tension by hiding the shark for the first half, The Thing never reveals the true form of the eponymous alien monster. By instead showing the thing’s increasingly terrifying impact on people, however, Carpenter managed to sculpt a masterpiece that Quentin Tarantino called “one of the greatest horror movies ever made.”

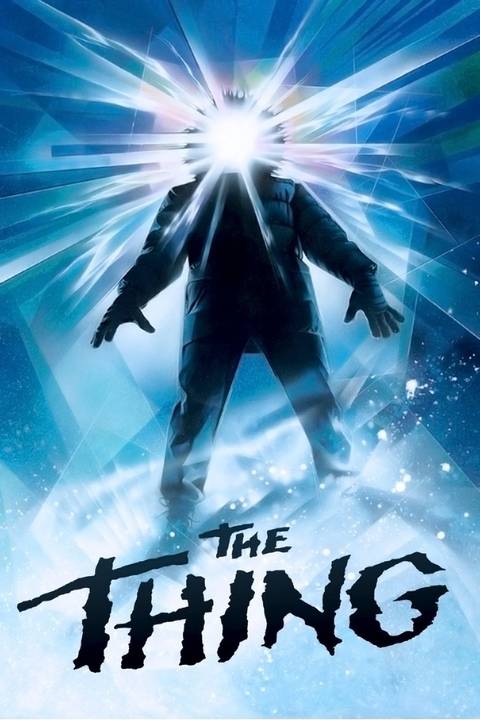

The Thing Eventually Earned Its Long-Overdue Acclaim

The Thing monster reveals itself in John Carpenter’s The ThingImage via Universal Pictures

The concept of cinematic gore hadn’t yet taken hold in the early 1980s, although movies like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (another Tarantino recommendation), Suspiria, and Alien had begun to push boundaries. That said, the vast majority of moviegoers hadn’t yet been desensitized to the extreme violence and grisly sequences popular in the modern era. So when The Thing came out, the first criticism on everyone’s minds was the hyperbolic excess of Rob Bottin’s work. Newsweek wrote that the film suffered by “sacrificing everything at the altar of gore,” reflecting the opinion of many contemporary critics.

Although Bottin was praised for his originality, the consensus did not change: The Thing was considered little more than a B-movie without anything real holding it together. Despite the enduring brilliance of a movie far ahead of its time, John Carpenter was initially affected by The Thing’s reception. He claimed that it “was hated, even by science-fiction fans,” who unfavorably compared it with recent genre like Blade Runner and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.

Many great films lambasted for being too original have been lost to history, but this was fortunately not the fate of The Thing. The rise of home video in the 1980s allowed it to spread through the country and the world, gradually building a devoted fandom. And while cult movies may not always be critically acclaimed, The Thing eventually became known as one of the best movies of all time.

Modern critics share the exact opposite opinion, collectively cementing it as a classic that deserved all the recognition and applause it never received. A wide array of publications, both print and online, have ranked The Thing among the finest works of both the sci-fi and horror genres. The RT score of 85% might be a little low, but that’s partly because of the older (and now outdated) reviews. Critics who formerly panned the plot as dull and sloppy were forced to reevaluate their opinions and recognize The Thing for what it is: a superbly calibrated exploration of human paranoia through the optics of an existential nightmare.

While it took far too long for The Thing to secure its current status, Carpenter suspects that timing was the problem. With the US undergoing a recession, viewers would have been less receptive to the film’s bleakly nihilistic outlook. Recessions may come and go, but The Thing will always remain a shining jewel of cinema. Among other filmmakers, Quentin Tarantino gushed about The Thing, calling it “one of the greatest horror movies ever made, if not one of the greatest movies ever made.”

Inspired by The Thing’s editing, narrative, and cinematography, Taraninto borrowed some elements while making The Hateful Eight. From longtime Carpenter collaborator Kurt Russell’s leading role and specific camera angles to unused parts of Ennio Morricone’s original score for The Thing, Tarantino’s 2015 film was an homage to John Carpenter and his crew. More interestingly, he also mentioned that his debut feature, Reservoir Dogs, was influenced by The Thing’s unbalanced equation of trust and paranoia.

The Thing Remains a Horror Masterpiece Even Today

Three researchers look at a UFO buried in snow at a distance in The Thing (1982)Image via Universal Pictures

At the heart of The Thing’s lofty reputation lies the practical effects, which were nothing short of groundbreaking. Before the era of CGI, Rob Bottin had to work with physical materials like wax bones, microwaved bubblegum, mayonnaise, Jell-O, K-Y Jelly, rubber veins, and creamed corn. This allowed him to literally sculpt the creature into a living nightmare.

Flesh stretches like rubber, limbs fuse and twist, chests become mouths with the ribs functioning as teeth, heads melt away at the necks and transform into spiders. Human bodies undergo metamorphoses that should have rendered them thoroughly deceased, but the titular Thing keeps them alive even in the most gruesome states. One would hope that the characters were fully dead by this point, but the story doesn’t make that clear. The culmination of the sci-fi movie’s practical effects was seen at the end, with a 50-person puppet made for the final Blair-Thing monster.

Audiences and/or critics who failed to understand The Thing’s exaggerated grossness need only have looked at the reactions of the human characters. In response to their bodies being invaded and colonized, they had to fear each other: The Thing’s ability to mimic a human being was arguably its most dangerous feature, and was teased early on when it took the form of a dog. This trait effectively sews discord among those desperate to avoid the fates of their colleagues.

Throwing characters into a pit of existential despair exposed some of the basest emotions of humanity, with distrust being the prime motivator for survival. The terror of being “infected” leads to the collapse of social cohesion: every man out for himself. The Thing serves as a dark reminder of the fragility of humanity when faced with the primal fear of the Other, of invisible infections, of simple betrayal. It’s a thin line between civilization and savagery, perfectly exploited by the mysterious Thing.

No matter the character’s background, whether an intelligent researcher or a pragmatic mechanic, desperation is a drug capable of changing a person from the inside out, like the Thing does in a literal sense. Personalities begin to clash as the paranoia spreads, kindling different emotions in each of them. Even the heroic endeavors of Carpenter’s groundbreaking protagonist, MacReady, fail to reignite unity, and the Thing ultimately “defeats” all of them.

The Thing’s legendary final scene, with MacReady and Childs presumably suspecting each other of being the final Thing, concludes with the same bitter note of distrust. Although Childs and MacReady accepted their fate after they were stranded in the bitter cold of Antarctica, they didn’t regain their faith. In fact, their final act of camaraderie illustrates the pointlessness of action, and not any sense of actual fellowship. Without killing them, the Thing managed to complete its objective: they will never trust each other again. And that’s the best way to tear the human race apart.

The Thing’s Legacy Made it a Landmark in the Horror Genre

Kurt Russell in John Carpenter’s The Thing.Image via Universal Pictures

There has been endless discussion on the fates of MacReady and Childs in its amazing ending. Fans have come up with several theories pointing to Childs as the Thing, but the lack of eye-glint and steamy breath was proven to be a technical issue. John Carpenter thought it could have gone either way, whereas Kurt Russell stated that fans were “missing the point” by overanalyzing the sequence. All that matters is the electric paranoia between the two final characters, even if Carpenter playfully claims to “know, in the end, who the Thing is.” On that note, The Thing’s 2002 video game adaptation appears to have an answer to this question. Whether it’s canon or not depends on Carpenter, but it does tie up a few loose threads.

The movie’s cinematic rigor and trailblazing accomplishments made it an eternal part of pop culture, with references and homages scattered across cinema, video games, and television. Iconic media like Stranger Things, The Mist, Resident Evil 4, Futurama, and even The X-Files have paid their tributes, and there was even a Pingu “adaptation” that John Carpenter praised. In addition to Quentin Tarantino, filmmakers such as J.J. Abrams, Rob Hardy, Neil Blomkamp, and Guillermo del Toro have cited The Thing’s impact on themselves and their careers. Even today, 43 years later, this is one theory-filled creature feature that never fails to shock and awe. Like the thing now presumably hibernating somewhere in Antarctica, The Thing can never die.

- Release Date

-

June 25, 1982

- Runtime

-

109 minutes

- Director

-

John Carpenter

- Writers

-

Bill Lancaster, John W. Campbell Jr.

- Producers

-

David Foster, Lawrence Turman

- Prequel(s)

-

The Thing