In the Curator’s Words is an occasional series that takes a critical look at current exhibitions through the eyes of curators.

By the time Harry Sternberg and his wife, Mary Gosney, moved from New York to Escondido in 1966, he was already a world-renowned artist, known around the globe for his prints and paintings, with his work first appearing at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931, when he was just 27.

Sternberg, who had a studio at 1718 East Valley Parkway in Escondido until he passed away in 2001, wasn’t just known for his artwork, though. He was a well-respected educator, too, teaching at the Art Students League of New York from 1933 to 1966.

Locally, he’s been the subject of a few exhibitions, including a retrospective at the California Center for the Arts, Escondido, and at the San Diego Museum of Art. The latter exhibition, in 1994, was curated by Malcolm Warner, a world-renowned curator who was, at the time, with SDMA in Balboa Park.

Warner, who’s devoting most of his time these days on the works of English painter John Everett Millais, most recently was the executive director of the Laguna Art Museum. He retired in 2020 after running the museum since 2012.

He took some time to talk about a new Sternberg exhibition, this time at the University of San Diego’s Hoehn Family Galleries.

Q: Tell us more about Harry Sternberg and why he was considered an influential figure in the world of printmaking.

A: Harry Sternberg was a famous name in the New York art world who lived his later years in Southern California. I got to know him when I was a curator at the San Diego Museum of Art. He was tough, straight-talking and physically imposing even in old age. We did an exhibition of his prints back then, in 1994, when he was turning 90. Most came from drawers in his jam-packed studio in Escondido.

It was such a treat to visit the studio and talk about art with him, usually over a good-sized shot of bourbon. He was an artist through and through, but absolutely no aesthete. If someone found a work of his beautiful, he wouldn’t object, but that was never the real point. For him, art was about expression. He wanted to put forth a truth about the world, as vividly and forcefully as he could.

He touched countless artists and art lovers through the prints he showed in New York exhibitions from the 1920s onward, and, perhaps most of all, through his teaching. From 1933 to 1966, he was an instructor at the Art Students League, where he was revered by colleagues and students alike. Even before moving to our part of the world, he loved teaching in the summer programs of the Idyllwild Arts Academy.

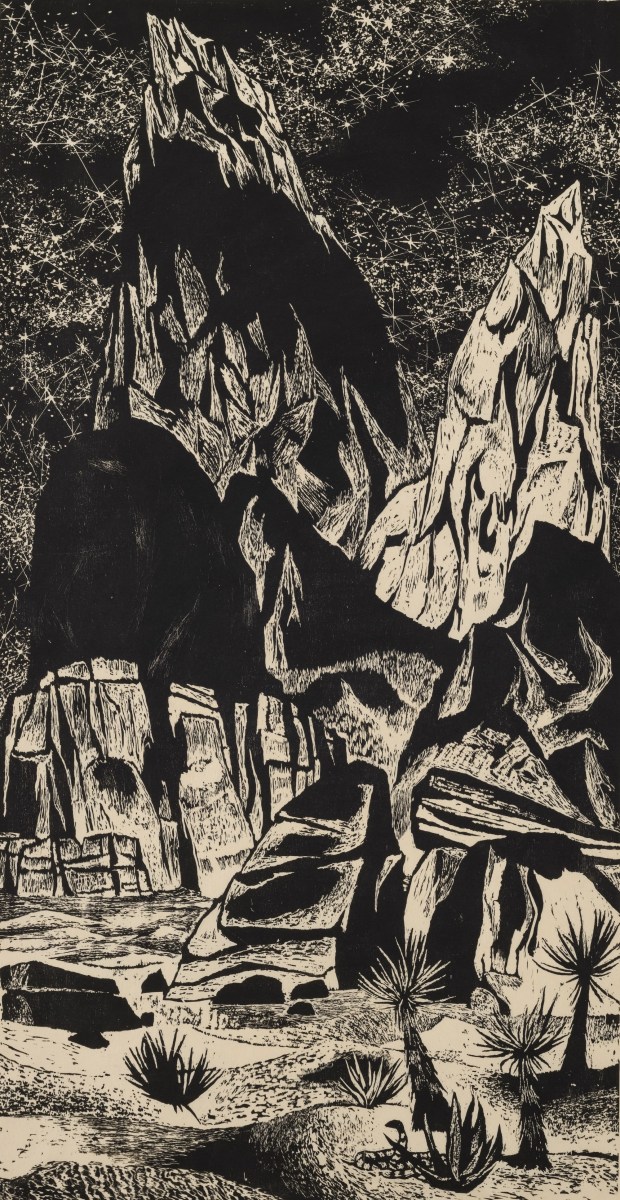

Harry Sternberg’s “Starry Night,” a power-tool woodcut, circa 1958-60 (Philipp Scholz Rittermann for SDMA)

Harry Sternberg’s “Starry Night,” a power-tool woodcut, circa 1958-60 (Philipp Scholz Rittermann for SDMA)

Q: With more than 50 Sternberg prints in this exhibition, this is quite an impressive assemblage of his work, including some from the San Diego Museum of Art. Is this one of the biggest exhibits of his work?

A: It’s pretty comprehensive, thanks in large part to loans from local collections. One of the many admirers of Harry and his works was the San Diego architect Norman Applebaum. His collection now belongs to the San Diego Museum of Art, and the museum kindly lent us everything we asked for.

Some of the largest exhibitions of Harry’s work have been in campus museums. He was self-educated, and a teacher himself, so he had a deep respect for education. I know he’d be pleased to see his latest big show at the University of San Diego, where the Hoehn Family Galleries are a showcase for the art of the print.

Q: For viewers, what should they be looking for when looking at Sternberg’s pieces?

A: Printmaking was Harry’s first love as an artist. He enjoyed the technical challenges, and mastered etching, lithography, silkscreen and woodcut in succession. His work is a great introduction to the expressive possibilities that the different forms of printmaking offer.

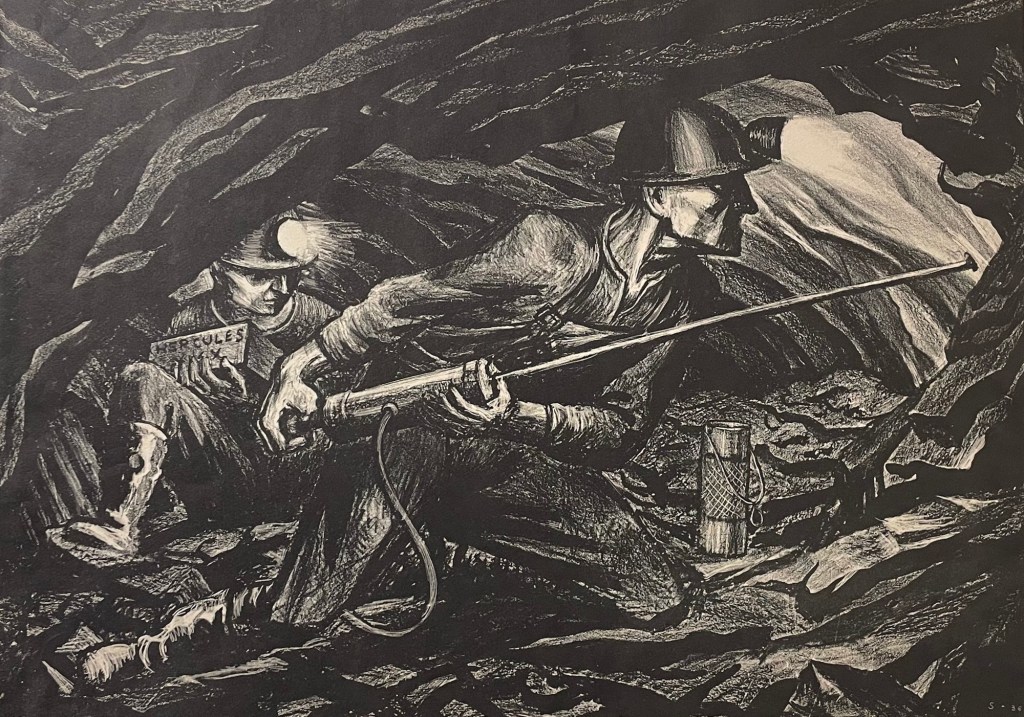

Apart from the silkscreens, his prints are black and white, which suits his bold, no-nonsense graphic style. His lithographs of coal mining subjects look like charcoal drawings, dramatic in the contrasts of light and dark. After falling in love with the deserts of California, he found in woodcut the perfect medium to bring out the rugged textures of nature.

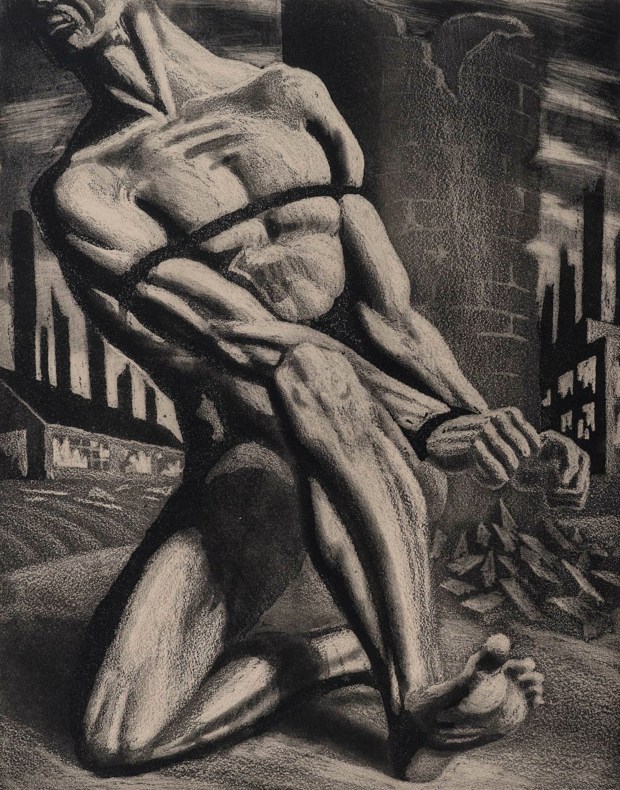

His curiosity led him to try every technique and type of subject, from construction sites and coal mines to symbolic dreamscapes, from realism to fantasy and satire. What makes a Sternberg a Sternberg is, above all, his way of using the body as a means of expression — often the naked body, which for him was humanity free of the here and now, all disguises off.

Q: What do you hope viewers will take away from this exhibition?

A: Harry knew antisemitism, lived through hard times and had a keen eye for injustice. He did some of his best work during the Great Depression. He never felt more fulfilled as an artist than in the company of coal miners in Pennsylvania. He wanted to show the world the toughness of their lives and bring home the fact that the system under which they labored should treat them better.

When he titled a group of lithographs “Dance of the Machine,” he meant literally machinery and at the same time the mechanisms of a sometimes unfeeling society. But he was no propagandist. At a time when many of his friends and fellow artists were Communists, he distrusted dogma and believed in enlightenment not revolution.

His “rage against the machine” was tempered by humor, hope and the principle that art must transcend the present moment. For him, workers like the coal miners were modern-day classical heroes, the embodiment of human resilience. “The theme is that mankind suffers,” he said, “yet can surpass whatever he faces.”

Harry Sternberg’s “Bound Man,” a crayon aquatint, circa 1947. (USD / Gift of Karen and Robert Hoehn)

Harry Sternberg’s “Bound Man,” a crayon aquatint, circa 1947. (USD / Gift of Karen and Robert Hoehn)

University of San Diego presents “Harry Sternberg: Dance of the Machine”

When: 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays to Fridays. Through Dec. 12 (closed on university holidays)

Where: Hoehn Family Galleries, Founders Hall, University of San Diego, 5998 Alcalá Park, San Diego

Admission: Free

Online: sandiego.edu/galleries