What happened to Eugene Williams is, to Deaunata Holman, “one of the most heinous crimes that could ever be committed.”

Like Holman, Williams was a Black kid growing up on the South Side of Chicago. On the second-hottest day of the year — July 27, 1919 — Williams, 17, headed to the lake with some friends to cool down. He never came home.

After Williams and his friends accidentally floated from the waters of a Black beach into a whites-only one, a man pelted them with stones from the shore until Williams drowned.

“That’s a story that’s going to always stick with me, even when I get older,” Holman, 26, said.

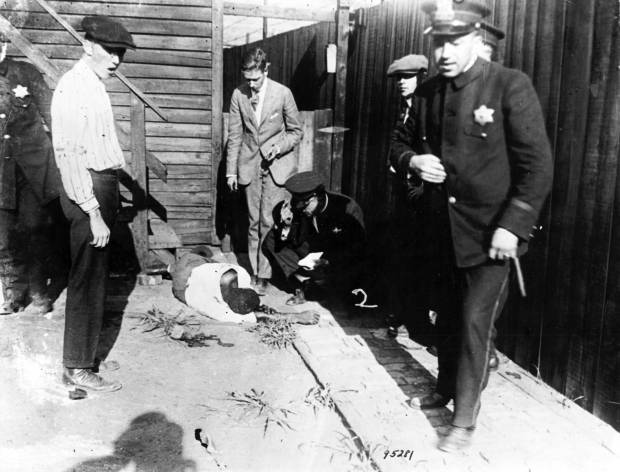

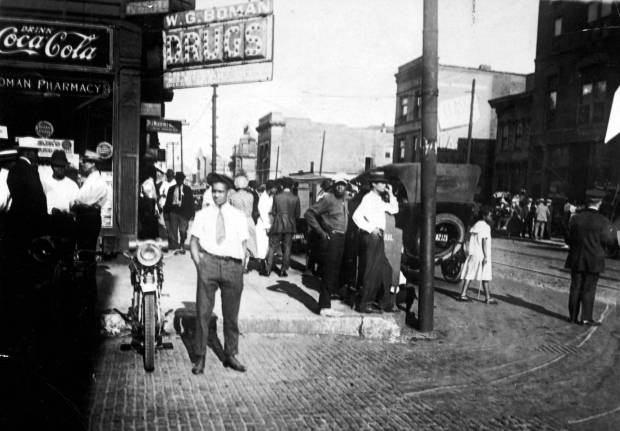

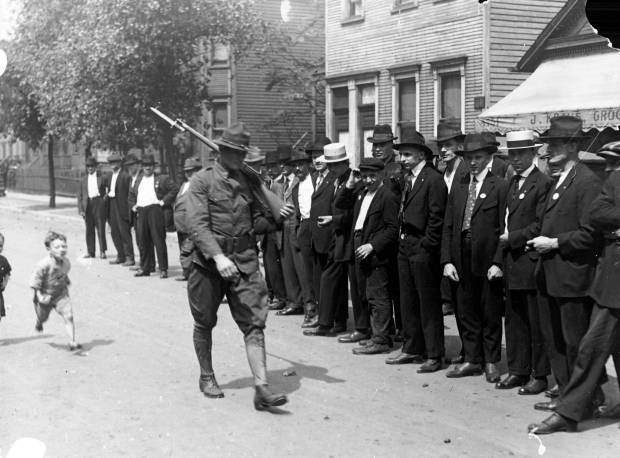

Williams’ death changed history, sparking the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. Stones and bricks were the instruments of torture awaiting Black Chicagoans who dared to venture outside during those bloody days.

By the time the state militia withdrew on Aug. 8, 1919, 38 people were killed, 537 were wounded, and more than 1,000 people lost their homes. Black residents made up two-thirds of those killed and also two-thirds of those arrested.

More than a century after Williams’ death, Holman and other artists have been making their own bricks. But instead of being wielded for violence, the brick markers have become tools for healing and public awareness.

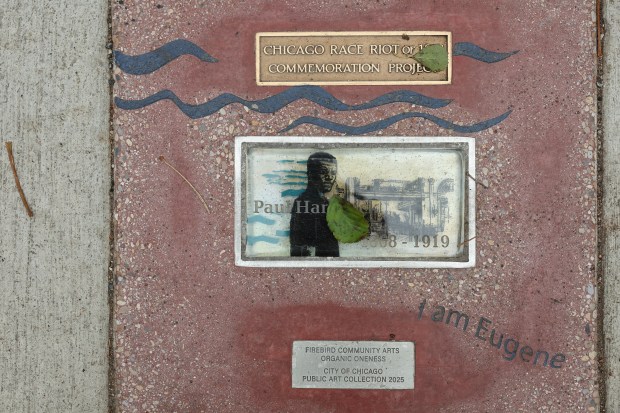

Since the riot’s centennial, the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project has pushed for a large-scale public art venture featuring those killed. Through partnerships with nonprofits Organic Oneness and Firebird Community Art — which creates the markers — glass bricks with a colored concrete frame were installed in Bronzeville last year. Each brick represents a person killed in the riot.

Now, the brick markers are in place in Canaryville, the Lower West Side and the Loop. Nineteen of the 38 planned bricks have been installed to date.

CRR19 co-director Franklin Cosey-Gay finds the project’s three newest markers, installed in July in the Loop, especially meaningful. On Saturday, he and co-director Peter Cole led a walking tour to those sites.

“Those that know about the race riot assume it was focused primarily in Black districts,” Cosey-Gay said between tour stops. “Show(ing) there were victims downtown is incredibly important.”

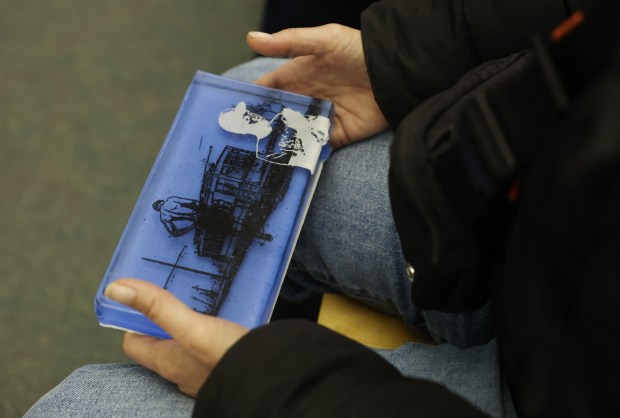

CRR19’s bricks are handmade by participants in Project FIRE, Firebird Community Arts’ rehabilitative program that enrolls young survivors of gun violence in glassblowing classes. By layering screen-printed images within the glass, the bricks combine historical photos relevant to the people who killed — whether depicting their place of work or their neighborhood — with the likenesses of the Project FIRE artists who helped make them. Even the texts embedded into the concrete frames were devised collaboratively during a Project FIRE workshop.

Holman started as a teen participant in Project FIRE in 2015. He’s now a teacher in the program. A sketch of him appears within another brick that will be installed in Grand Boulevard by the end of the year, honoring B.F. Hardy, a Black commuter who was dragged from a streetcar and killed.

“We put our faces in (them) because we’ve been through gun violence, we’ve been through racial acts,” Holman said.

Two of the three Loop memorials sit on heavily trafficked streets. Robert Williams, a 41-year-old janitor, was chased and stabbed in the block where the Harold Washington Library now stands; his memorial is on the sidewalk between the library’s main entrance and the intersection of State and Van Buren streets.

A ground marker with the name of Paul Hardwick etched in a glass brick is at the intersection of South Wabash Avenue and West Adams Street as part of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project, Nov. 8, 2025, in Chicago. Hardwick was one of 38 people killed during the riot. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

A ground marker with the name of Paul Hardwick etched in a glass brick is at the intersection of South Wabash Avenue and West Adams Street as part of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project, Nov. 8, 2025, in Chicago. Hardwick was one of 38 people killed during the riot. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

The same day, Paul Hardwick, a 51-year-old waiter at the Palmer House Hotel, was chased and shot by a different roving mob. His marker sits at the southeast corner of Adams Street and Wabash Avenue, at the foot of the “L” station stairs. The Palmer House’s east doors, through which Hardwick likely left work, are visible from the memorial.

A third marker, further south at State and 9th streets, is in the block where Harold Brignadello, a 35-year-old Rock Island resident, was killed. A 1922 city-commissioned report on the riot — which Cole considers the “Bible” among primary sources on the events of 1919 — concluded that Brignadello had been part of a group throwing stones at a Black woman’s home. He was shot by someone taking refuge within the home.

“There were mobs of people who looked like me roaming the streets of Chicago, looking for people who looked like Franklin,” Cole, who is white, said of Cosey-Gay, who is Black, during a presentation before the tour.

Show Caption

1 of 27

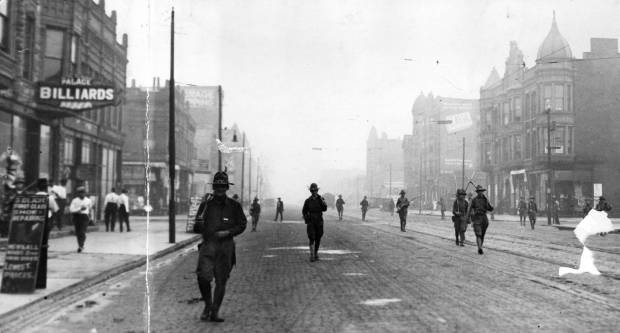

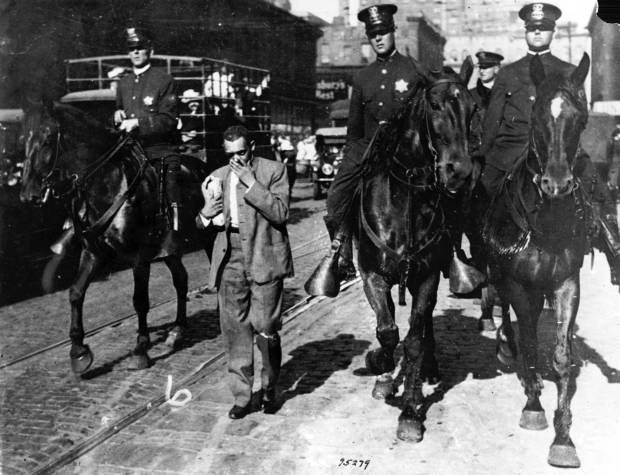

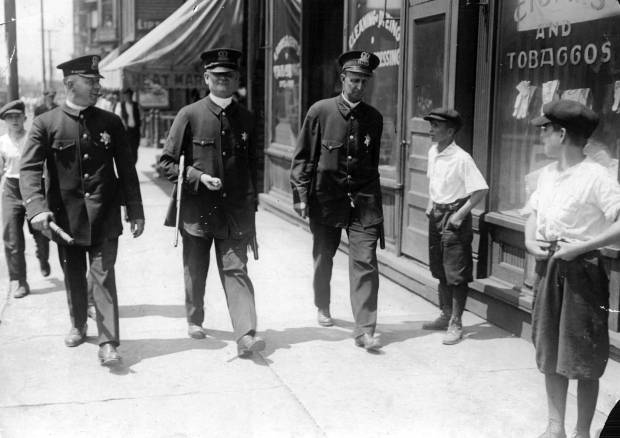

The state militia was called in to quell the violence on Chicago’s South Side during the 1919 race riots. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)

Relaying this history prior to the walking tour, CRR19 operations director Myles Francis said the riot is “deeply connected to the challenges we continue to face.”

“We don’t talk much about the race riot of 1919,” Francis said. “We spend a lot more time talking about the Chicago Fire, Al Capone and other stories that are maybe exciting but don’t require us to examine our history and role in society in the same way.”

Cole, a history professor at Western Illinois University in Macomb, had long dreamed of a public art project to feature those killed in the race riot. After traveling to Germany, he was inspired by the Stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, memorializing Holocaust victims across Europe.

“You’re walking down the streets thinking about what to eat later, and then you stumble across the fact that, right here, someone was a victim of the Holocaust,” Cole told Saturday’s tour attendees. “That was a provocation. It’s intervening in your ordinary life.”

In 2019, a century after the race riot, Cole and Cosey-Gay were introduced at the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ, which famously hosted Emmett Till’s funeral in 1955. The two men complemented one another: Cole brought historical rigor to the project, while Cosey-Gay — the director of the University of Chicago Medicine’s Violence Recovery Program and a violence prevention organizer since the 1990s — had community connections.

And there was one other thing. “I picked him up from the Red Line station and found out that he cycled,” Cosey-Gay told the Tribune. “I like to cycle.”

Before long, Cole and Cosey-Gay were organizing bike tours under CRR19’s banner, as well as walking tours and lectures. CRR19’s annual bike tour, which coincides with the anniversary of the riot, remains its marquee event.

Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project co-directors Franklin Cosey-Gay, left, and Peter Cole, right, speak with an attendee of a panel discussion about the project at the Harold Washington Library, Nov. 8, 2025, in Chicago. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project co-directors Franklin Cosey-Gay, left, and Peter Cole, right, speak with an attendee of a panel discussion about the project at the Harold Washington Library, Nov. 8, 2025, in Chicago. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Funders took note of their efforts. After George Floyd’s 2020 death inspired a surge in giving to racial justice causes, CRR19 received $75,000 from Niantic, the augmented reality company behind Pokémon Go. That was followed by $50,000 from the Chicago Monuments Project, a collaboration among the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Park District that was formed during the same period.

When the park district was awarded a $6.8 million grant from the Mellon Foundation, CRR19 received an additional allotment of $250,000. Cosey-Gay said that put CRR19 “over the hump” to pay for materials and installation, which will continue through the spring.

Future markers will expand the project to Bridgeport, Back of the Yards, Englewood and Washington Park. One will be installed outside the National Public Housing Museum, again drawing more visibility to the project.

“Public art meets you where you’re not expecting to be met,” Cole said. “It’s there 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, year in and year out.”

An attendee holds a sample glass brick used in the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project during a panel discussion at the Harold Washington Library, Nov. 8, 2025, in Chicago. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

An attendee holds a sample glass brick used in the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project during a panel discussion at the Harold Washington Library, Nov. 8, 2025, in Chicago. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Holman, the Project FIRE artist, is already taking that longterm view. On hot days, he still thinks of Williams. But on this cold Saturday afternoon, walking between monuments, Holman imagined himself visiting the bricks 10 to 20 years in the future.

“Making a piece is like owning your own piece, owning your own glass. Can’t nobody make a replica of your glass,” Holman said. “I’m gonna go take my son or daughter right there, and be like, ‘I did something to remember our old past.’”

Hannah Edgar is a freelance writer.