Hidden deep within Tanzania’s misty Eastern Arc Mountains, scientists have uncovered three remarkable frog species that defy nature’s usual rules. Instead of laying eggs that hatch into tadpoles, these frogs give birth to tiny, fully developed young. This rare form of reproduction challenges one of biology’s most familiar life cycles. The discovery, born from a blend of historical specimens and cutting-edge DNA science, is changing what we know about amphibian evolution.

A Leap Beyond Tadpoles

In one of the most striking biological revelations in recent years, a team of herpetologists has identified three new African frog species that give live birth—completely bypassing the tadpole stage. These findings, published in the journal Vertebrate Zoology, are reshaping long-held assumptions about how amphibians reproduce.

“It’s common knowledge that frogs grow from tadpoles – it’s one of the classic metamorphosis paradigms in biology,” explained Professor Mark D. Scherz from the Natural History Museum of Denmark. “But the nearly 8,000 frog species actually have a wide variety of reproductive modes, many of which don’t closely resemble that famous story.”

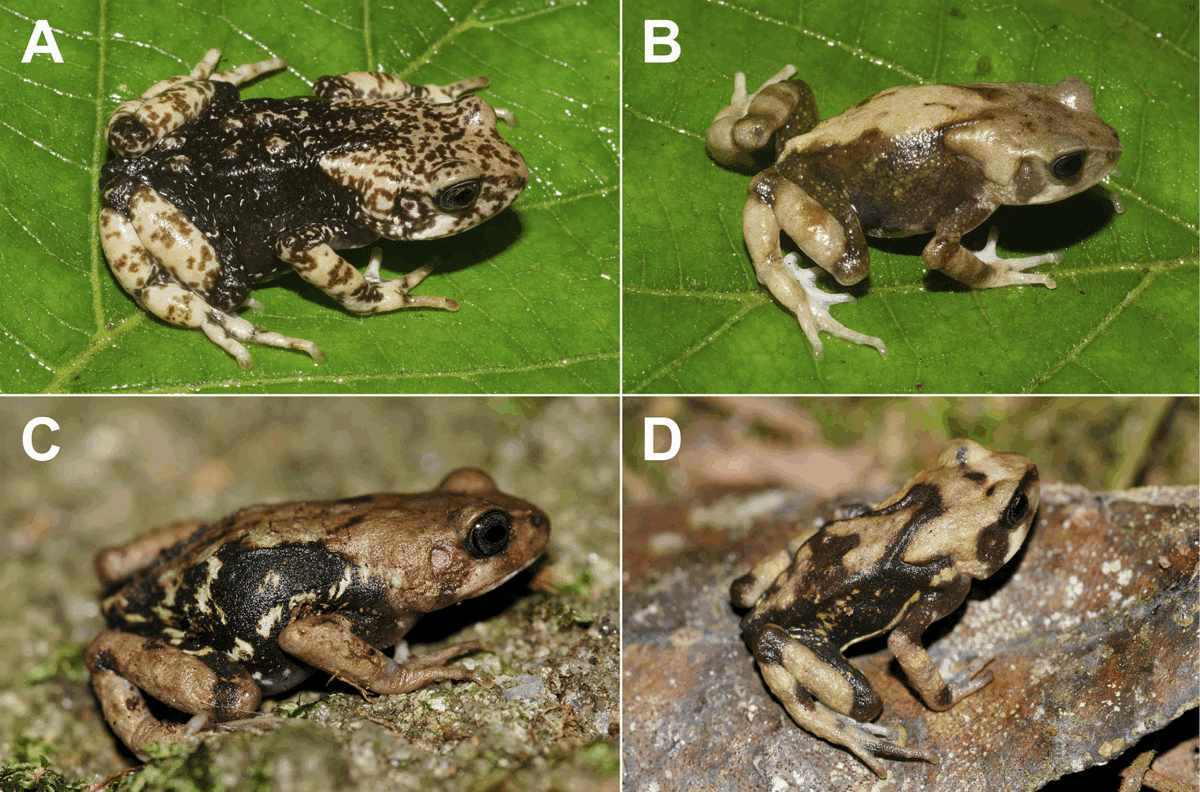

The newly discovered frogs, belonging to the genus Nectophrynoides, were found in the cool, damp forests of Tanzania’s Eastern Arc range. Unlike most amphibians that depend on water for their larval stage, these frogs nurture their young internally, giving birth to fully formed miniature frogs. This mode of reproduction is exceptionally rare—occurring in less than one percent of all frog species—and its discovery in Africa has stunned biologists who previously believed such traits were mostly confined to South America and Southeast Asia.

From Museum Drawers To DNA Sequencing

The story of these frogs began not in the field, but in the archives of history. More than a century ago, a German scientist named Gustav Tornier had documented an unusual Tanzanian frog capable of live birth. For decades, its identity and relationship to modern species remained a mystery, until researchers applied museomics—a technique that extracts DNA from ancient, preserved specimens.

Dr. Alice Petzold of the University of Potsdam, who led the genetic analysis, managed to trace the lineage of these long-forgotten specimens to modern populations. This fusion of old-world discovery and new-world science allowed researchers to unlock hidden diversity within the Nectophrynoides lineage.

“Phylogenetic work from a few years ago had already let us know there was previously unrecognized diversity among these toads,” said Christian Thrane, the study’s lead author. “But by traveling to different natural history museums and examining hundreds of preserved toads, I was able to get a better idea of their morphological diversity, so we could describe these new species.”

Through this process, scientists confirmed the existence of three distinct species, each adapted to its own microenvironment within Tanzania’s forested highlands. The discovery underscores the value of museum collections as time capsules of biodiversity—windows into species that might have otherwise vanished without ever being studied.

Fragile Forests, Vanishing Frogs

While these discoveries are scientifically thrilling, they carry a sobering message. The lush forests of the Eastern Arc Mountains—often described as “islands in the sky”—are under severe threat. Expanding farmland, logging, and mining have fragmented the once-continuous canopy into isolated patches.

Many species of Nectophrynoides are now restricted to tiny habitats surrounded by human activity. Some, like Nectophrynoides asperginis, are already extinct in the wild, while others, such as Nectophrynoides poyntoni, have not been seen in decades. Conservationist Dr. Michele Menegon, who works in the region, warns that each discovery of a new species may also represent a race against time to protect it.

The research not only expands the known diversity of African frogs but also reinforces the urgency of preserving the delicate ecosystems they inhabit. Every new species described adds a layer to our understanding of evolution—and reminds us of what could be lost before it is ever known.