The woman’s cries echo down the hallway, shattering the usual silence of a courtroom. Her four-year-old daughter joins in, beginning to cry in her father’s arms as the family is surrounded by half a dozen masked agents. The only other sounds are the whispers of volunteers, who are quickly trying to identify the family about to be detained, and the cameras of journalists witnessing the scene. It’s impossible to hear what the immigration officials are saying to the Venezuelan couple, as they are cornered. In a matter of seconds, the family is escorted toward a staircase and, for hours, will remain “missing” somewhere in 26 Federal Plaza in New York City: Donald Trump’s immigration hell.

This 41-storey federal building, officially named the Jacob K. Javits Building but known simply by its address, has become the epicenter of the Trump administration’s immigration offensive in the nation’s most populous city, home to 8.5 million people, three million of whom are immigrants. The Lower Manhattan skyscraper houses both the main offices of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the city, on the fifth and ninth floors, and several immigration courts spread across the 12th and 14th floors. Every week, hundreds of migrants, most of them asylum seekers, arrive here for appointments or hearings that until recently were routine but have now become ambushes.

On floors 12 and 14, amid hallways with stained white walls and under fluorescent lights that, in the absence of windows, trick the mind and obliterate the sense of time, federal agents patrol daily. Some are in plainclothes, others wear bulletproof vests and are identified as ICE or Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers. They are armed and almost all have their faces covered, with ski masks that only reveal their eyes.

Among them is one who struts around the building at ease. He’s tall, burly, looks down his nose at everyone, and it’s clear he’s in charge. A migrant couple leaves their hearing, and the officer stands behind them. The couple is startled, but the agent only wanted to scare them. “See you later,” he says to them in Spanish. And he turns away with a smile that’s visible even beneath his balaclava.

In general, officers position themselves at the doors of the courtrooms and near the elevators migrants use to arrive and then leave after their appointments. Like hunters stalking their prey, they wait, observe… and strike. Once they identify their target, they go for it.

There have been dozens of videos circulating on social media or in the local press showing the brutal arrests taking place inside this building: officers violently throwing themselves at individuals to pin them against the wall, families forcibly separated, officers pushing to the ground anyone who gets in their way, whether they are members of the press or distraught family members, and even elected officials ending up in handcuffs for intervening in the arrests, as was the case with Comptroller Brad Lander, the city’s finance director.

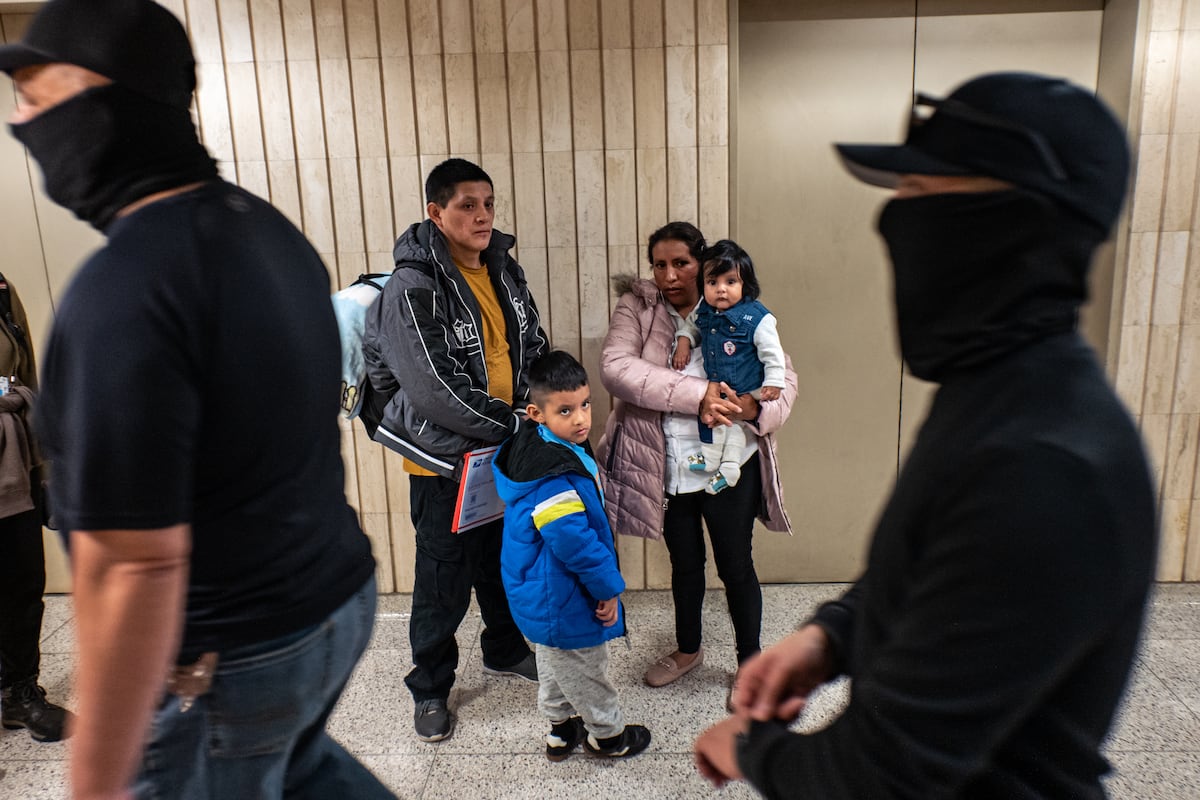

A Venezuelan family being questioned by federal agents inside the Federal Plaza building.KLAUS GALIANO

A Venezuelan family being questioned by federal agents inside the Federal Plaza building.KLAUS GALIANO

These scenes contrast sharply with those seen in other cities, such as Los Angeles and Chicago, where President Trump’s mass deportation campaign has been implemented through large-scale raids and immigration operations. In New York, one of the few raids occurred on October 23, when agents descended on busy Canal Street, a hub for street vendors, and arrested about 10 people. And while arrests have taken place in and around immigration courts in other cities — after the Republican administration repealed the long-standing rule prohibiting arrests in courthouses, which were considered “sensitive locations” — the Federal Plaza case stands out due to the sheer volume of arrests. As of the end of July, half of the 3,300 migrants arrested by ICE in New York City since Trump’s inauguration were detained at Federal Plaza, according to figures from the Deportation Data Project, an initiative that collects and publishes government data. About three-quarters of them had no criminal record.

It’s nearly impossible to predict who agents will arrest. Benjamin Remy, an attorney with the New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG), who spends several days a week working with migrants at Federal Plaza, explains that until recently, ICE primarily arrested people whose cases had been dismissed. “Then we saw them start arresting people who had been in the United States for less than two years, and then anyone who had applied for asylum. Now, it’s still unclear what criteria ICE is using, and we’re basically operating under the assumption that anyone who isn’t a U.S. citizen is at risk of being detained,” he says.

Until two weeks ago, those arrested were always individuals. However, agents have begun detaining entire families, according to volunteers who visit the building daily to observe the court proceedings and the lawyers who accompany the migrants. On October 30, the family from Venezuela was at least the third to be detained inside Federal Plaza.

“We have to cover all the exits!”

The abduction sparked hours of chaos as volunteers searched for the Venezuelan couple and their four-year-old daughter. The Federal Plaza building does not have a facility for holding families. ICE has holding cells on the tenth floor, but they are not equipped for families or children. In recent months, these cells have become increasingly overcrowded as migrants are now held there for days instead of the hours they used to spend while being processed. The space has been criticized for overcrowding and unsanitary conditions, and a federal judge issued an order in September requiring that basic sanitation measures be ensured at the facility.

Aware of this, immediately after immigration agents took the family up the stairs to the 12th floor, the volunteers rushed to the elevators to go down to the building’s lobby. “We have to cover all the exits!” they shouted. They thought there were only two possibilities: that the agents would take the family out through one of the four exits on the first floor, or that they would take them through the basement, somewhere the volunteers can’t access.

However, there was no sign of the family in the lobby. Nor on the ninth floor, at the ICE office, where the volunteers went in search of answers. For hours, no one knew what had happened to the family that EL PAÍS had witnessed being detained. “It’s a missing family,” said Father Fabián Arias, incredulous, a man who has spent 20 years going to New York immigration courts to accompany asylum seekers.

Father Fabián Arias comforts an Ecuadorian migrant woman after her hearing at Federal Plaza.KLAUS GALIANO

Father Fabián Arias comforts an Ecuadorian migrant woman after her hearing at Federal Plaza.KLAUS GALIANO Journalist Vural Elibol is treated by paramedics after being knocked to the ground, along with other journalists, by federal agents on October 1.KLAUS GALIANO

Journalist Vural Elibol is treated by paramedics after being knocked to the ground, along with other journalists, by federal agents on October 1.KLAUS GALIANO Sometimes, agents wait for people to enter the elevator to try to detain them, thus avoiding the presence of the press.KLAUS GALIANO

Sometimes, agents wait for people to enter the elevator to try to detain them, thus avoiding the presence of the press.KLAUS GALIANO Facade of 26 Federal Plaza, in Lower Manhattan.Klaus Galiano

Facade of 26 Federal Plaza, in Lower Manhattan.Klaus Galiano

After pressure from lawyers from the migrant advocacy organization Make the Road and the offices of several New York members of Congress, the agents released the mother and child on Thursday afternoon.

More than a week later, the father remains in ICE custody and has been transferred to a detention center in the neighboring state of New Jersey, while the mother now wears a GPS ankle monitor so authorities can track her, and the four-year-old girl is devastated. “The whole experience and being separated from her dad was, and continues to be, very traumatic for the child. Even when she sees the police drive by on the street, she gets upset. She asks if the police will bring her father back,” says Paige Austin, an attorney with Make the Road, which is handling the father’s case pro bono.

The family, whom this newspaper is not identifying at the request of their lawyers, was at Federal Plaza that Thursday for their first hearing in their asylum case. Minutes before being detained, the judge had scheduled their next appointment for next year. Austin maintains that neither of the parents “has criminal convictions” that could have been used as a reason for their detention: “We don’t believe there is anything in their history that justified the actions that were taken.”

Families torn apart

On September 8, Diana Rúa and Jesús Antonio Murcia, a Colombian couple married for a decade, traveled from Queens to Federal Plaza. On the cusp of autumn, they lined up that chilly morning, entered the building, took the elevator, and went straight up to the 12th floor, where the “hooded ones,” as Rúa, 40, calls them, are located.

As she left her court appearance, Rúa saw them pointing at her husband. “I told him, ‘Honey, go, get out of here.’” That day, they took several women and children into custody, and they also arrested her 58-year-old husband. “They handcuffed him, they took his ring and watch themselves, and they handed me his wallet.” To this day, ICE has not returned Murcia’s wedding ring to her.

Rúa left the building alone, wearing an electronic monitor on her right ankle, which she is forced to bathe and sleep with, and which has caused sores and back pain. “They don’t have to put this on me, I’m not going to escape,” she says. “Where to? They’ve already taken my heart, my life.” Her husband, Murcia, was deported last month.

Diana Rúa, a Colombian migrant living in New York.KLAUS GALIANO

Diana Rúa, a Colombian migrant living in New York.KLAUS GALIANO

The couple arrived in the U.S. across the border in August 2024, along with their 15-year-old son. They fled, Rúa says, the violence in Comuna 13 of Medellín. They settled in Queens, in a $1,700 apartment that Rúa can no longer afford, worked cleaning houses, and built a life that was short-lived. Five months ago, their son couldn’t take it anymore. The fear of being detained by ICE became a nightmare. He stopped eating and sleeping. He also refused to go to school. “He didn’t want to be locked up in an immigration center and he couldn’t bear it.” The young man left on his own for Colombia.

“I came to the United States and encountered something I didn’t expect. I feel persecuted here, just as if I were in my own country,” Rúa says. Now she is awaiting another hearing with the judge, also at Federal Plaza, the place she doesn’t want to return to.

It’s a fear that’s spreading among the city’s immigrant communities. “From the courts to the streets, immigrants are absolutely terrified,” says attorney Remy of NYLAG. “The most striking examples are found in the everyday scenes at 26 Federal Plaza: immigrants breaking down in tears upon seeing armed and masked officers, panic attacks in the courtrooms themselves, and the reality that, every day, entire case files are left empty because immigrants have decided not to risk showing up. People are in an impossible situation, and they know it: attend court and risk being arrested, or stay home and receive a deportation order in absentia, losing any chance of winning their case.”

This fear was supposed to be nonexistent in a sanctuary city like New York, which just three years ago became a haven for migrants expelled from Republican states like Texas — sheltering them, providing them with food, clothing, and education — but which now participates in the crusade that promises to expel them. Upon returning to the White House, Trump immediately extended an olive branch to Democratic Mayor Eric Adams, promising to shield him from a federal corruption case. Almost overnight, with Adams’s complicity, the same city that received more than 230,000 migrants amid an unprecedented border crisis became one that allows masked agents to patrol the halls of its courthouses. In addition to Federal Plaza, its neighbor, the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway, and the immigration court on Varick Street, have been used for detentions.

It’s a reality that Zohran Mamdani, the newly elected socialist mayor of the city, promises to change. After a campaign in which he pledged to stand up to Trump, during his victory speech on November 4, the young politician addressed the president directly and made his intentions clear: “New York will remain a city of immigrants. A city built by immigrants, powered by immigrants. And starting tonight, led by an immigrant.”

However, while waiting for Mamdani to take office in January and champion the cause of migrants as he promises, hundreds of families will still have to make the difficult decision to attend their appointments as required by law, knowing what lies behind the doors of places like Federal Plaza.

Federal agents detain a migrant after leaving immigration court in June 2025.Olga Fedorova (AP)

Federal agents detain a migrant after leaving immigration court in June 2025.Olga Fedorova (AP)

Jessica Supliguicha, from Ecuador, remembers the last day she saw her husband. It was outside Federal Plaza on the morning of September 6. Jorge Guaraca, 38, had a court date, but Supliguicha, nine months pregnant, wasn’t allowed inside. She waited outside for him from 7:30 a.m. until noon. “We were afraid, we knew something could happen, but we went anyway,” says the 40-year-old.

A call from her lawyer told her what had happened inside. Guaraca had been arrested and was being held on the tenth floor, in the ICE cells. Supliguicha wanted to see her husband. “I asked, and they told me I couldn’t,” she says, tears welling up. She hasn’t seen him since that morning. Then came the calls from the detention centers, and later from Ecuador, to where her husband was deported. During one of those calls, Supliguicha was able to introduce him to her daughter, the baby she had to give birth to alone on October 5.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition