San Diego County last month agreed to pay $16 million to the family of Hayden Schuck after his 2022 death in sheriff’s custody, the single largest payout yet in a succession of lawsuits filed over jail deaths in recent years.

With county lawyers now defending at least 20 additional cases and more settlements expected, Sheriff Kelly Martinez has come under mounting pressure to show she’s making progress in improving medical and mental health care across the county’s seven jails.

Earlier this month, Martinez appeared before the Citizens’ Law Enforcement Review Board, the county’s civilian oversight body known as CLERB, to outline steps she’s taken to better care for people in custody.

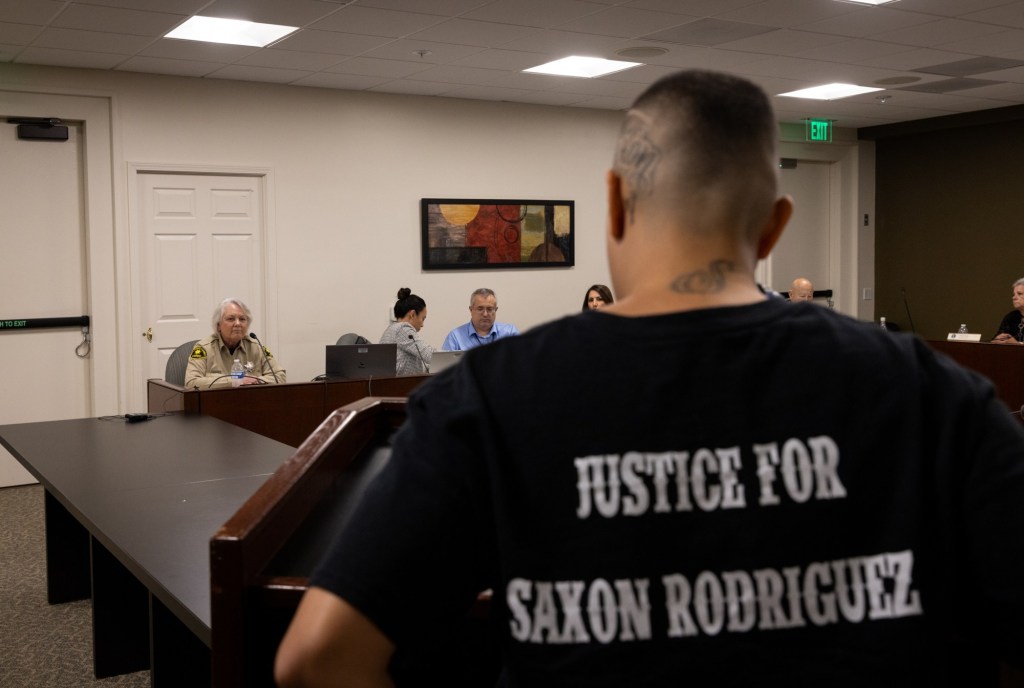

CLERB has increasingly become a hub for criticism of the Sheriff’s Office. Each month, family members of people who have died in San Diego jails and their advocates attend the meetings, calling for greater transparency and stronger oversight.

Brett Kalina, CLERB’s executive officer, told The San Diego Union-Tribune that Martinez’s presentation was requested by the board. It was her second appearance since taking office in January 2023.

Martinez described steps the Sheriff’s Office has taken to improve medical care in jails, like having three directors of nursing — up from one — and hiring certified nursing assistants to ease a shortage of registered nurses.

Each of the county’s three intake jails now has emergency room-trained doctors, she said, who can assess a person’s medical needs immediately upon booking.

“This is an improvement from having nursing staff or mental health clinicians attempt to identify medical or mental health issues to relay to a doctor at a later sick call,” a Sheriff’s Office spokesperson said in response to follow-up questions about Martinez’s CLERB presentation.

Martinez said her office also created new standards for what hospitals must check when a person is taken for medical clearance before booking. Questions about gaps in communication between outside providers and jail intake staff have come up in several lawsuits tied to jail deaths.

Martinez noted there were no suicides in 2024 and there have been none so far this year.

“Our focus has been on preventing suicides from occurring,” Martinez told the board. “We’re not taking a victory lap by any means, but we’re very proud of our record.”

Under former Sheriff Bill Gore, whose tenure lasted nearly 13 years, San Diego County jails averaged about three suicides a year, including 22 between 2013 and 2016. The rate was among the highest in the state and contributed to a growing outcry over jail conditions.

After a spate of overdose deaths, the Sheriff’s Office purchased new body scanners, added drug-sniffing dogs and began random screenings to curb smuggling. Medication-assisted treatment is now offered to help ease withdrawal symptoms that drive people to seek out drugs inside jail.

Martinez said these efforts have reduced the overall amount of drugs being smuggled into jails.

She also described how the department is using technology to track people with health issues. Two of the county’s largest jails will soon begin testing biometric monitoring devices designed to alert staff when someone is in medical distress. The department’s IT division created a phone app that gives deputies instant access to medical records of people they’re checking on.

Still, challenges remain.

On Dec. 9, Martinez will present to the Board of Supervisors the findings of a two-year review of jail infrastructure needs. She said the cost of necessary upgrades could reach $1 billion. The Vista Detention Facility, she told CLERB, “needs to be completely torn down and rebuilt.”

Martinez said Proposition 36 — the 2024 voter-approved measure that toughened penalties for repeat drug and theft offenses — has further strained capacity.

The law has resulted in some 500 more people being detained in her jails, pushing the average daily population to roughly 4,400. Martinez said she will need more deputies, medical staff and mental health clinicians to handle the additional people.

San Diego County jails have faced scrutiny for years from the media, auditors and civil rights attorneys. The crisis peaked in 2022, when 20 people died in custody, including one man who died just after being granted what’s known as a compassionate release.

That same year, a state audit found serious and deadly lapses in care. Sheriff Gore announced his retirement shortly before it was released.

Brett Kalina, executive officer, center, listens during a CLERB meeting at the San Diego County Administration Center on Tuesday, Sept. 3, 2024, in San Diego. (Meg McLaughlin / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Brett Kalina, executive officer, center, listens during a CLERB meeting at the San Diego County Administration Center on Tuesday, Sept. 3, 2024, in San Diego. (Meg McLaughlin / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Since Martinez took office, the pace of deaths has slowed, but they have not stopped. Thirteen people died in custody in 2023, nine in 2024 and nine more so far this year.

Among them were two deaths this past July that immediately raised concerns about the jails’ treatment of people with mental or cognitive health problems. According to sworn statements by other men in their unit, Corey Dean and Karim Talib both died after deputies were repeatedly warned that they needed medical help.

“Mr. Dean would spend his days screaming and yelling,” Miguel Angel Lopez Altamirano wrote in his declaration. “He would rub feces on his face and into his beard.

“I thought he needed serious medical and mental health help,” Lopez Altamirano added. “The deputies told me there was nothing they could do.”

Two weeks after Dean died in the Vista jail, Karim Talib died in a similar manner in the downtown Central Jail. People locked in nearby cells repeatedly told deputies that Talib needed medical attention, but none came, according to sworn testimony.

The Sheriff’s Office is also defending a class-action lawsuit challenging the quality of medical care provided to people in San Diego County jails. After more than five years, the trial is scheduled to start early in the new year.

While the county has already agreed to upgrade jails to comply with the federal Americans with Disabilities Act, its lawyers are still fighting broader claims that jail conditions amount to unconstitutional neglect.

A related hearing is scheduled for next week in federal court, where plaintiffs are asking a judge to limit how long people with serious mental illness can be held in solitary confinement.

That request, filed last month, includes more than a dozen sworn declarations from people held in administrative separation — the sheriff’s term for solitary confinement. Eleven men and three women described receiving little or no mental health treatment and almost no human contact.

They said they are often confined to their cells for 23 hours a day or more, with toilets that overflow, trash that piles up and infestations of rats and insects.

“When I do get to go into the dayroom, I am placed in a cage and treated like an animal,” wrote detainee Ismael Betancourt. “The only way that I can socialize while in this cage is through screaming at other people because I am too far away from them.”

Several detainees said they are never told why they are there or when they might be released to regular housing.

Paloma Serna speaks during a press conference on a $15 million settlement in connection to the death of her daughter, Elisa Serna, in downtown San Diego on Tuesday, July 2, 2024. Elisa Serna, 24, died in 2019 when she was left unattended after collapsing in jail. (Kristian Carreon / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Paloma Serna speaks during a press conference on a $15 million settlement in connection to the death of her daughter, Elisa Serna, in downtown San Diego on Tuesday, July 2, 2024. Elisa Serna, 24, died in 2019 when she was left unattended after collapsing in jail. (Kristian Carreon / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

At the CLERB meeting, members pressed Martinez for information about housing placements and other issues that have surfaced in the board’s investigations, such as claims that calls for help via jail intercom systems go ignored.

Martinez said a review of the housing classification process is underway but acknowledged limits imposed by overcrowding.

“Almost everyone has some special classification or issue or concern,” she said. “We’re constantly trying to figure out where we can safely put people.”

Vice Chair Jim Mendelson asked Martinez for data on deputy discipline — including suspensions, firings and resignations related to misconduct — which Martinez promised to provide.

Sixteen members of the public signed up for public comment after Martinez spoke, many of them family members of people who died in custody.

Paloma Serna, whose daughter Elisa died in the Las Colinas women’s jail in 2019, emphasized that families and community advocates have been driving jail reforms.

The Serna family received a $14 million settlement from the county and another $1 million from a jail medical contractor. The settlement also required the sheriff to institute new training and policy changes.

Activist Darwin Fishman echoed Serna’s comments, saying much of the department’s progress stems from the litigation it’s fought, not voluntary reform.

“It’s because of lawsuits — literally over dead bodies,” he said. “Families lost loved ones. The lawsuits forced these changes.”