Coloradans’ mental health is finally improving, despite high levels of self-reported loneliness and widespread problems affording necessities, according to a poll of roughly 10,000 people.

The Colorado Health Access Survey, released Wednesday, polled residents from February through July, asking about their economic and mental health struggles. It also touched on demographic data and whether respondents had health insurance.

Here are some of the top takeaways from the survey, which the Colorado Health Institute conducts in odd-numbered years.

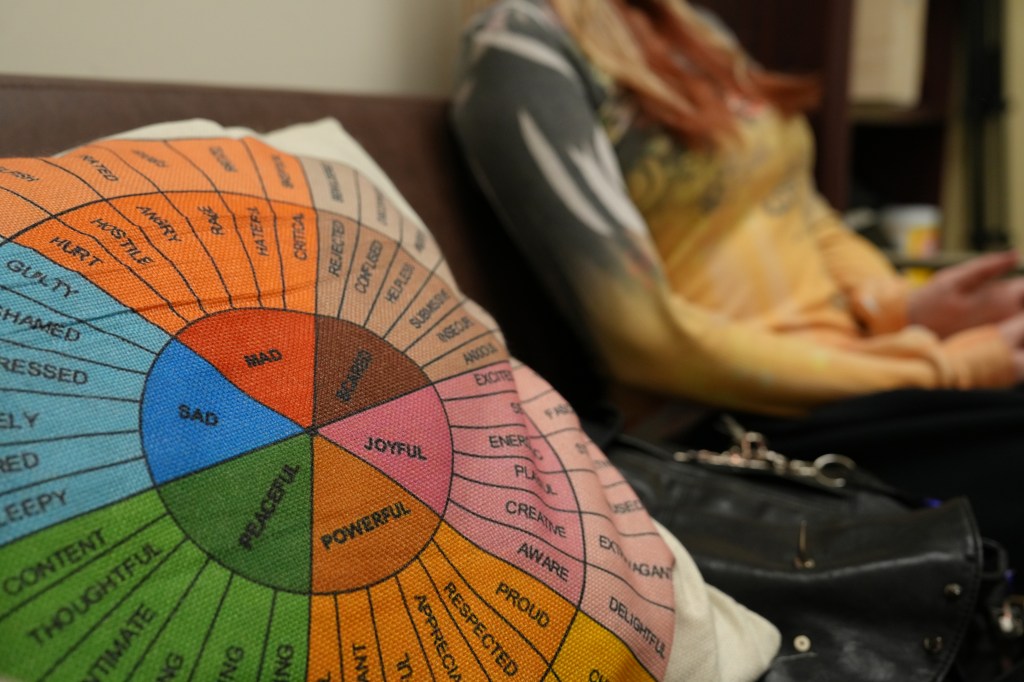

Fewer people report poor mental health

This year, 20.5% of respondents reported their mental health was poor on at least eight days in the previous month, down from a high of 26.1% in 2023.

Rates of poor mental health had increased each time the survey went out from 2015 to 2023. While the current number is an improvement, it still represents roughly double the share of people who said their mental health was poor a decade ago. (The survey goes out to a random sample of addresses every year, so it can’t determine if specific people felt better over time.)

The only group that saw a statistically significant reduction in people reporting poor mental health was adults ages 30 to 64. Improvements among younger people, along with a slight increase in reported poor mental health among older adults, were small enough that they could represent random fluctuations, survey project leader Suman Mathur said.

Fewer people said they went without needed mental health care last year than in 2023.

The survey couldn’t differentiate how much of the change was due to improving mental health and how much came from greater access to care, but it noted that more people reported talking to professionals about their mental health. About a third of respondents said they had spoken with a health care provider about their mental health in the previous year, which was a 50% increase from 2017.

1 in 5 people report being lonely

About 22% of people reported loneliness, based on how often they felt they lacked companionship, were left out and were isolated from others. The survey didn’t ask that question in previous years, so it couldn’t give any insight into whether loneliness was getting worse or better.

People who reported loneliness were twice as likely to rate their physical health as poor, and they were four times as likely to say the same of their mental health. The survey, though, couldn’t determine if illness caused loneliness — or if loneliness worsened health outcomes.

Denver residents reported the highest rate of loneliness in the state, for reasons that aren’t totally clear, said Lindsey Whittington, the data and analysis manager at the Colorado Health Institute. The question established a baseline for how common loneliness is in various groups but didn’t go into factors that might contribute, they said.

Respondents who identify as transgender or nonbinary, have a disability, are adults younger than 30 or are American Indian reported higher rates of loneliness.

Health insurance coverage barely budged

About 5.9% of respondents reported they didn’t have health insurance this year. That wasn’t a significant difference from the 4.6% in that category in 2023 or the 6.5% or so in the years before the pandemic, Mathur said.

The numbers may be reassuring to people who worried about mass coverage losses following the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency in 2023. During the emergency, state Medicaid programs didn’t disenroll people unless they died or moved out of state.

When it ended, the programs had to determine who still qualified, raising concerns that people would lose insurance because they didn’t complete the paperwork.

About 21% of people had coverage through Medicaid this year — higher than in 2019, but down from 30% near the end of the public health emergency. Conversely, the share of people reporting job-based coverage rose for the first time since the pandemic began, though the increase didn’t fully make up for people losing Medicaid.

Significant minority struggles to afford essentials

A third of Coloradans struggled to afford health care, housing costs or food, according to the survey, and about 3.5% reported they had trouble paying for all three.

Difficulty affording health care was most common, with 27.5% saying they didn’t visit a doctor or fill a medication because of costs. That was roughly in line with previous years, Whittington said.

About 11% of people reported having difficulty paying their rent or mortgage, and roughly the same share said they ate less than they thought they should because they couldn’t afford sufficient food.

Hardship isn’t shared equally

Perhaps unsurprisingly, uninsured people were the most likely to report going without physical or mental health care. People covered by Medicare had the fewest problems finding or paying for care, followed by those with job-based coverage.

Respondents who identify as American Indian, Black or Hispanic reported more problems affording necessities than people who said they were white or Asian. Renters had more problems with affordability than homeowners, and people who lived alone fared worse than those who lived with family or roommates.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get health news sent straight to your inbox.