Toward the end of the Senate Finance Committee retreat in Radford on Thursday, a special guest was invited to address the senators who will have a big say in what the state budget looks like.

“Nothing better than spreadsheets!” declared Gov.-elect Abigail Spanberger.

That may be, but she couldn’t have loved the numbers that were in them. For about three and a half hours Thursday, the senators heard one dour report after another about the future of the state’s economy.

These reports came from both inside and outside state government — from economists with S&P and the Federal Reserve as well as Senate Finance staffers — but they all painted the same picture: Virginia’s economic growth is slowing down and may not improve anytime soon.

Some of the reasons can be attributed to President Donald Trump and his policies — tariffs that have driven up prices and introduced uncertainty that is spooking investment, and reduced immigration that is now slowing economic growth.

Other reasons are beyond the command of any president: an aging population, declining birth rates and the rise of artificial intelligence that is already eliminating many jobs.

These warnings are hardly new. We’ve heard them all before, most recently in the economic forecast issued by the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia. Still, the steady repetition of all these warnings, from multiple sources, maybe ought to get our attention.

“The economy is undergoing a number of structural changes and they can obscure where we are in the business cycle,” advised Anna Kovner, executive vice president and director of research for the Federal Reserve Bank in Richmond, who was one of the speakers.

In other words, some of the things we’re seeing may be short-term (and reversible with different policies) but others are more fundamental changes that we all need to understand before we formulate policies, be they left or right.

Perhaps the best way to do this is to present some of the data that the senators (and governor-elect) saw during their afternoon meeting at Radford University. I will divide this into two sections: what’s happening now and what’s forecast to happen.

Part 1: What’s happening now

The Senate Finance Committee retreat at Radford University drew a large crowd. Photo by Dwayne Yancey.

The Senate Finance Committee retreat at Radford University drew a large crowd. Photo by Dwayne Yancey.

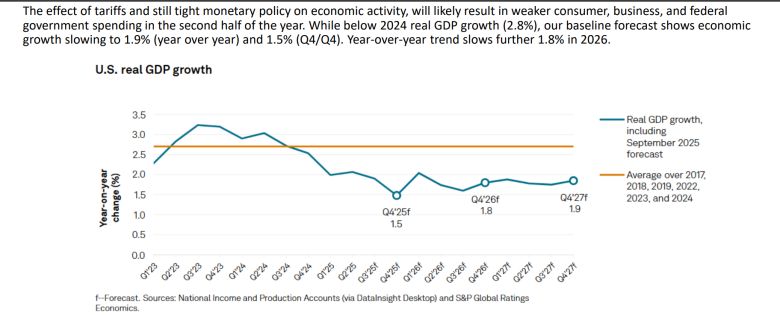

Tariffs are slowing the economy, not growing it

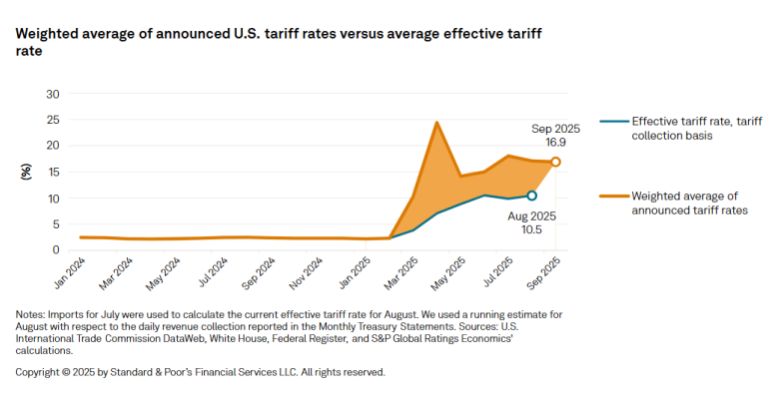

How tariffs have increased. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

How tariffs have increased. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

In 2024, the effective tariff rate on goods imported into the United States was 2.3%, according to data presented by Thomas Zemetis of S&P Global. For the past two months, it’s been 11% and is expected to rise to 17% based on what the Trump administration has announced. This amounts to a tax increase on American consumers. Trump’s stated goal is to discourage imports and encourage domestic production, but some imports can’t be produced domestically (example: coffee) and some supply chains simply can’t readjust that fast. Some may simply decide not to.

“The greater risk from tariffs isn’t high prices,” Zemetis said. “It’s uncertainty.” His firm is seeing investment slow — rather than accelerate — because investors don’t know what the rules will be.

Consumer spending is driven by high-income Americans

Economists speak of a “K-shaped recovery,” where the top line of the K is doing well and the bottom line is not. The economy isn’t driven by Wall Street or Washington; it’s driven by ordinary consumers, whose spending accounts for 70% of the economy. As we’ve come out of the pandemic, upper-income Americans have done well — others have not.

In the early 1990s, the top 10% of Americans, income-wise, accounted for about 36% of consumer spending. Today it’s 50%. That’s masked what’s really happening in the economy — overall, it appears to be doing well, but it’s propped up by one specific group of high-income spenders, according to information presented by Senate staffer Tyler Williams.

(My observation: This is likely why Spanberger did so well in the election. Her whole campaign was built around the theme of “affordability,” while Republican Winsome Earle-Sears rarely mentioned the economy but when she did, she insisted all was well. The overall statistics may say that but many voters clearly felt otherwise.)

Economic growth is being powered almost entirely by one sector: artificial intelligence and data centers

In the first half of 2025, the nation’s gross domestic product grew at an annualized rate of 1.6%, Williams said. However, if you took AI and data centers out of that, it would have been only 0.1%. That means GDP growth doesn’t truly reflect the overall economy. Moreover, there’s a risk here that an AI bubble will burst, Williams said in his presentation: “If AI adoption rates fail to materialize or lead to profits, stock market prices will have to adjust, which would likely cause well-to-do consumers to reduce spending.”

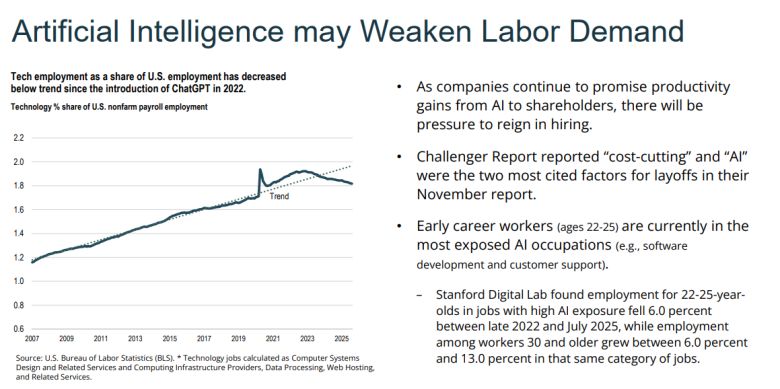

Artificial intelligence is reducing job growth, especially for young adults

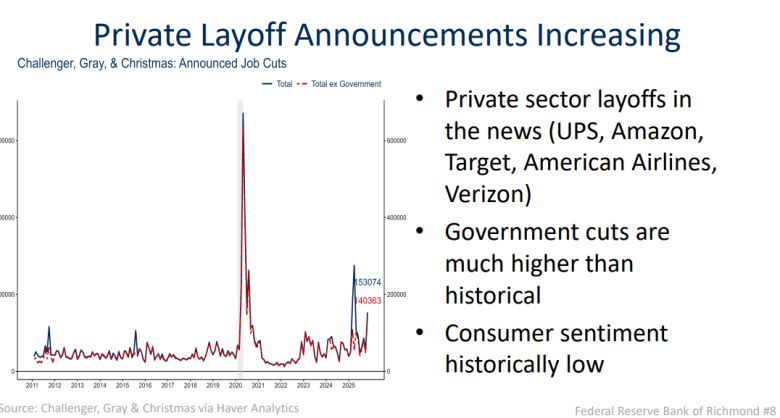

AI investment may be driving the nation’s economic growth, but it’s also costing people jobs. Private sector layoffs are increasing, Kovner said, and artificial intelligence is playing a role in some of those. The Challenger Job-Cut Report, a popular economic report, says in its most recent edition that “cost-cutting” and “AI” were the two most commonly cited reasons for job reductions.

The pandemic, she said, helped accelerate artificial intelligence. When companies found it hard to find enough workers as we came out of the pandemic, they invested in automation, she said. Now we’re seeing the impact of that. Early-career workers are the ones feeling the biggest pinch. The Stanford Digital Lab found that “employment for 22-25 year-olds in jobs with high AI exposure fell 6% between late 2022 and July 2025” while older workers saw their type of jobs grow between 6% and 13%.

We often think of technology jobs as a sure-fire growth sector but the legislators saw data that suggested the opposite — that since ChatGPT was introduced in 2022, technology jobs as a share of U.S. employment has actually declined:

Since ChatGPT was introduced, technology’s share of jobs in the U.S. has declined. From Senate Finance Committee presentation.

Since ChatGPT was introduced, technology’s share of jobs in the U.S. has declined. From Senate Finance Committee presentation.

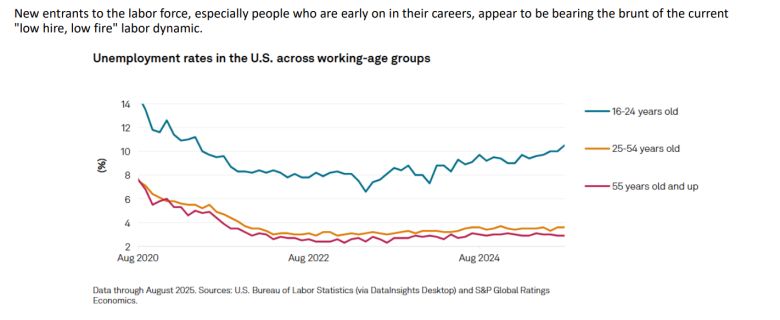

One phrase heard throughout the afternoon was that we’re in a “low-hire, low-fire” economy — few people are laid off, but few people are being hired. Younger workers “appear to be bearing the brunt” of this economy, Zemetis said. Unemployment rates for younger workers are trending upward while the rates for older workers aren’t.

Unemployment for young workers is trending up. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Unemployment for young workers is trending up. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

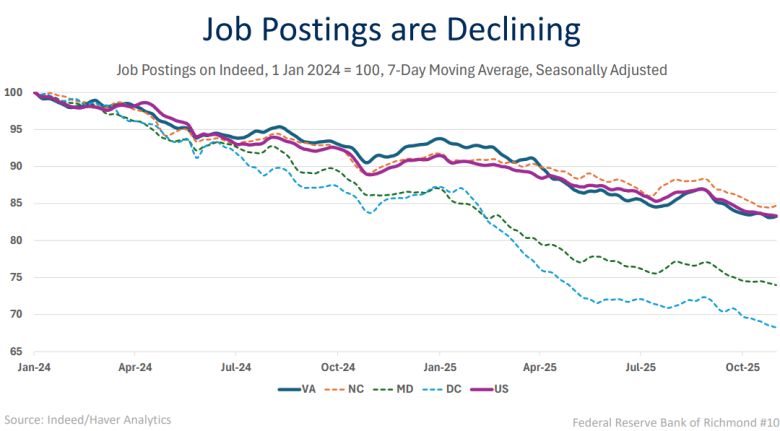

Unemployment is relatively low but job postings are declining

Job postings are declining. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Job postings are declining. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Kovner presented this chart that shows how job postings have declined since January 2024. Virginia’s rate has tracked the national rate so we’re better off than Maryland and the District of Columbia, but the number of job postings has still gone down — another symptom of that “low-hire, low-fire” economy.

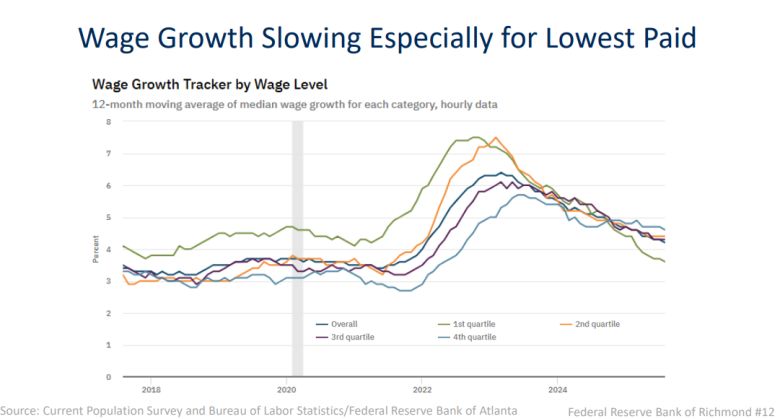

Wage growth is slowing for lower-income workers

Wage growth is slowing. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Wage growth is slowing. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Wages shot up after the pandemic when the economy reopened but there were fewer workers to be found (partly because a lot of workers retired early). But now wage growth is slowing, and those at the lower end are falling behind — which plays into the consumer spending trends noted above.

Layoffs are increasing

Layoffs from private employers are increasing. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Layoffs from private employers are increasing. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Federal job reductions have gotten a lot of attention in Virginia because the federal government is the largest employer in the state. However, layoffs from private employers are also increasing. The chart above shows how they’re starting to spike nationally. (The big spike is the pandemic.)

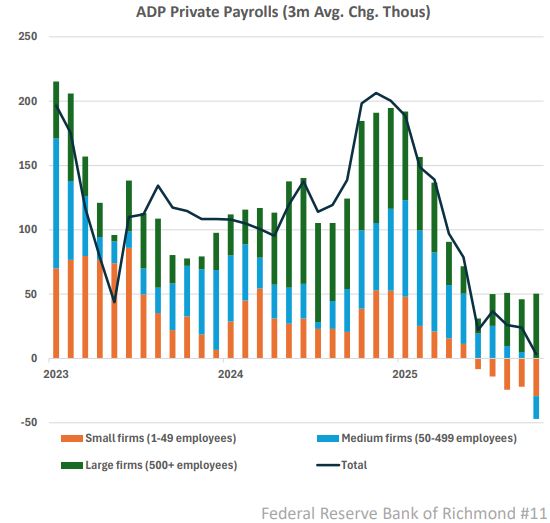

Small businesses are reducing payroll

Small busineses have been reducing payroll. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Small busineses have been reducing payroll. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Here’s another chart Kovner showed to illustrate how job growth is slowing: Large firms are hiring but small ones (and most recently medium-sized ones) have been reducing the number of workers. We’re still seeing job growth but the composition of who’s hiring has changed.

My observation: This poses a challenge for Democrats in the General Assembly, who want to raise the minimum wage. That would address the slowing wage growth, assuming there are employers who can pay higher rates. However, what impact would higher minimum wages have on these small businesses that are already reducing workers? It’s hard to imagine that a higher minimum wage would inspire them to incur more costs; would they instead hire fewer workers, which would only make jobs harder to find for the younger workers who are already finding it hard to enter the workforce?

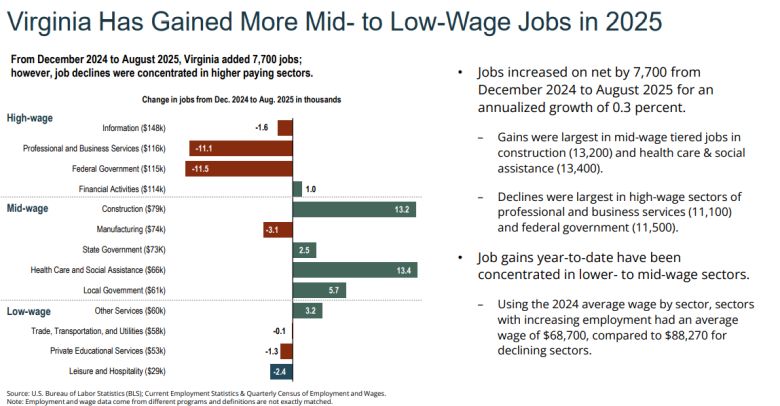

Virginia is losing high-wage jobs and creating lower-wage jobs

How Virginia’s jobs are changing. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

How Virginia’s jobs are changing. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Virginia is growing jobs (albeit slowly) but beneath the surface we’re seeing an important, and ominous, shift. We’re losing high-wage jobs and gaining lower-wage ones. Drawing on federal data, Miller presented a chart that showed how the job sectors where Virginia is losing jobs have average wages of $88,720 per year while the ones we’re adding average $68,700. Economically speaking, we’re trading down.

Much of this is driven by federal job cutbacks (those jobs average $115,000 a year) and related losses in federal contractors who come under the category professional and business service ($116,000). However, we’re continuing to see declines in manufacturing ($74,000). The fastest-growing job sector is health care and social assistance ($66,000). The federal cutbacks are a direct result of Trump policies; the health care growth reflects the demands of an aging society. The manufacturing reductions fit decade-long patterns that have defied multiple presidents.

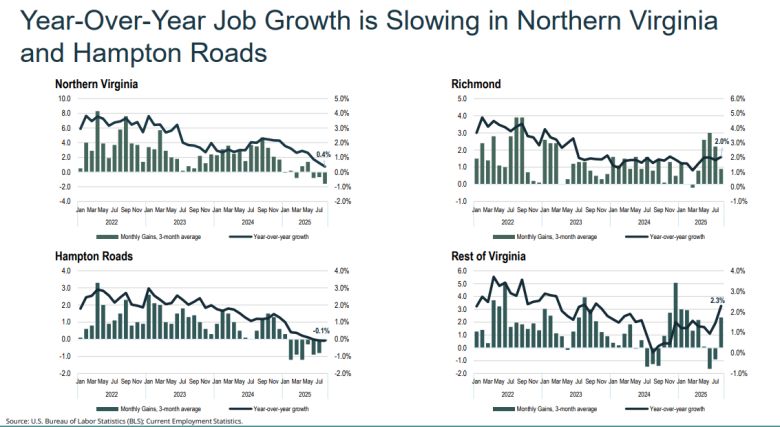

Virginia’s two biggest metro areas are seeing slow job growth

Job changes in the state’s biggest metro areas. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Job changes in the state’s biggest metro areas. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

That’s Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads. Our two biggest economic engines are sputtering.

Part 2: What the forecasts say

Former state Sen. Emmett Hanger, R-Augusta County, talks with Lt. Gov.-elect Ghazala Hashmi. Photo by Dwayne Yancey.

Former state Sen. Emmett Hanger, R-Augusta County, talks with Lt. Gov.-elect Ghazala Hashmi. Photo by Dwayne Yancey.

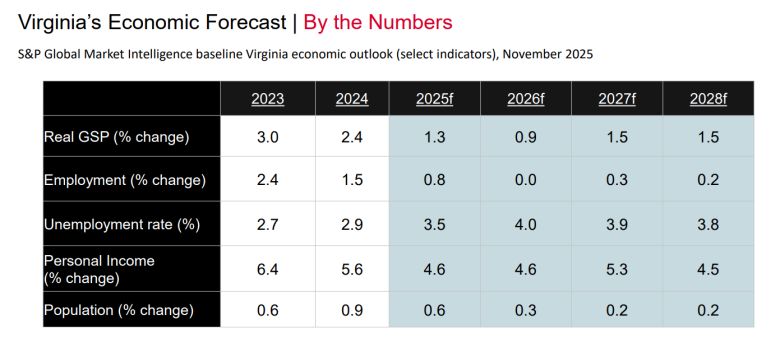

Virginia’s economy is going to slow down

The S&P forecast for Virginia. GSP is the state version of GDP — gross domestic product, in this case, just for Virginia. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

The S&P forecast for Virginia. GSP is the state version of GDP — gross domestic product, in this case, just for Virginia. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Zemetis showed off this chart that forecasts no job growth in the coming fiscal year — and slow job growth in fiscal years 2027 and 2028. “I’ve been quite downcast on the view,” Zemetis said. (Spanberger might be wondering why she asked for this job; the task ahead looks pretty daunting.)

GDP growth is projected to be below average. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

GDP growth is projected to be below average. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

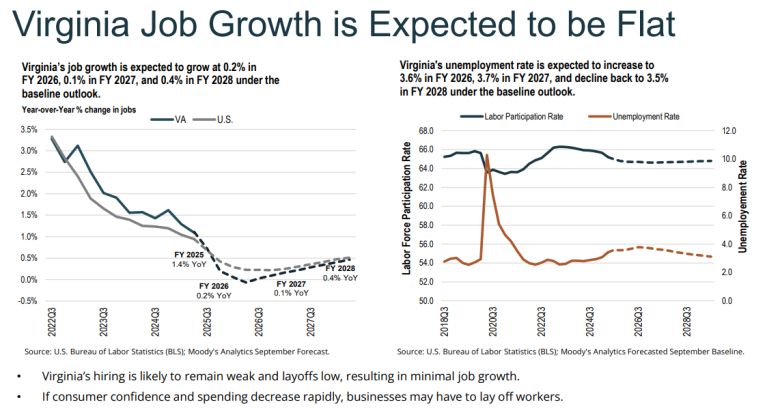

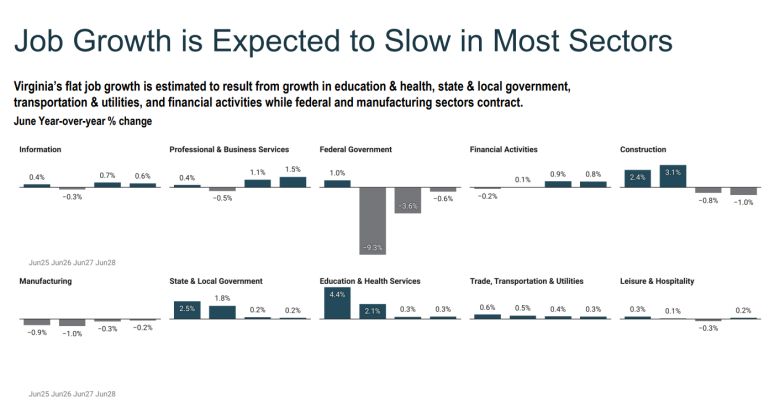

Williams presented these charts, which say much the same thing: sluggish job growth (with continuing declines in federal jobs and manufacturing).

Virginia’s job growth is projected to be flat. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Virginia’s job growth is projected to be flat. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Viginia’s projected job growth by sector. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Viginia’s projected job growth by sector. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

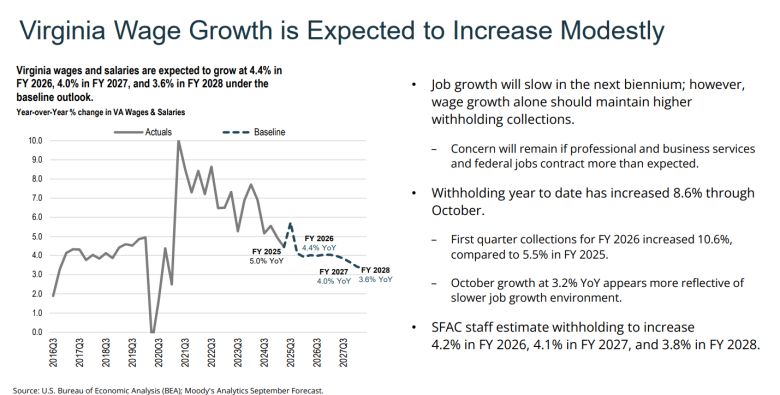

Wages won’t grow much.

Virginia’s forecast for wage growth. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Virginia’s forecast for wage growth. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

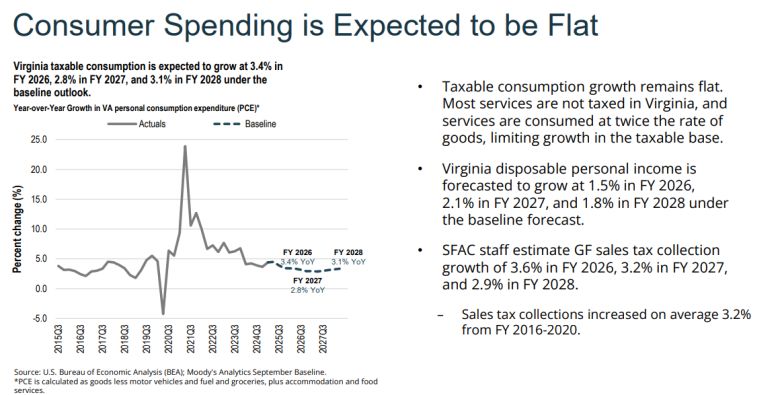

Neither will consumer spending.

Virginia’s forecast for consumer spending. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Virginia’s forecast for consumer spending. From presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Slowing population growth will slow the economy

We have an aging population — a combination of longer life spans and lower birth rates that’s skewing things toward the gray end of the spectrum. As people retire, incomes drop, Zemetis pointed out, and that lowers consumer spending — which slows the economy.

If we had more immigration, we’d have more people earning and spending money. While economics might call for more immigration, our politics are calling for exactly the opposite, so some of this will be a crisis of our own making. (We should remember that some economists believe that reduced immigration in the 1920s exacerbated and lengthened the Great Depression because there were fewer consumers to fuel the economy.)

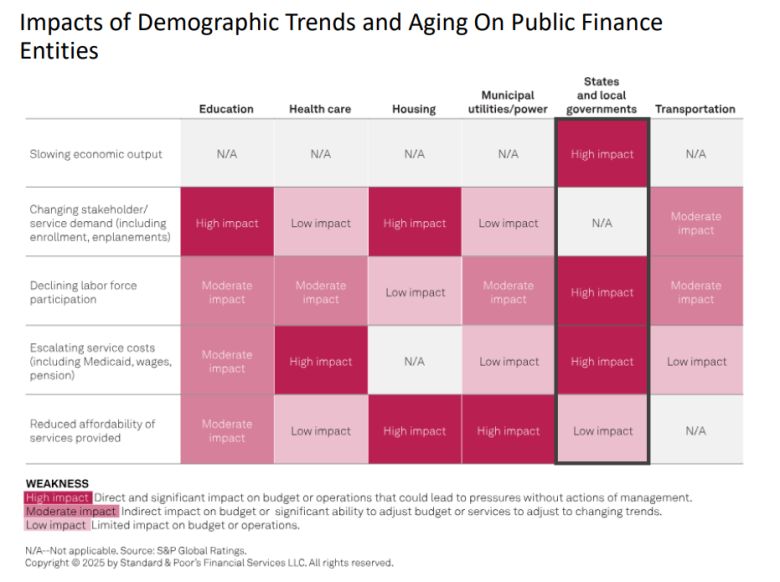

Zemetis showed off this chart that highlights some of the ways that an aging population will have an impact on the economy:

Projected demographic impacts on various sectors. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

Projected demographic impacts on various sectors. From S&P presentation to Senate Finance Committee.

If you haven’t had enough and want to see all the charts, you can find them here. I noticed that Spanberger was taking lots of notes. She slipped out without taking questions so I didn’t have a chance to ask her what she thought, but I’d be curious what she learned and how that will shape her policies over the next four years.

Want more political news? We’ve got more in our weekly political newsletter, West of the Capital. This week I look at the Democratic candidate who thinks redistricting is a bad idea, where Roanoke author Beth Macy’s fundraising compares with other candidates statewide, and which Republican senators are in districts that Spanberger carried this fall. Sign up here:

Related stories