On the northeastern shores of Japan, a strange, gelatinous creature recently appeared in the surf. Pale blue and semi-transparent, it looked like a jellyfish—until scientists realized it wasn’t one. Instead, it was something potentially more dangerous: a previously undocumented species of Portuguese man-of-war.

Spotted on Gamo Beach in Sendai Bay by marine biologist Yoshiki Ochiai, the creature was sent to Tohoku University for analysis. What researchers uncovered was both unexpected and revealing. The specimen represented a new species, genetically distinct from any previously known man-of-war organism.

They named it Physalia mikazuki, a reference to the crescent-moon crest of the famous samurai Date Masamune. But more than a curiosity, its sudden arrival marked a potential biogeographic shift—a tropical drifter appearing far north of its known range.

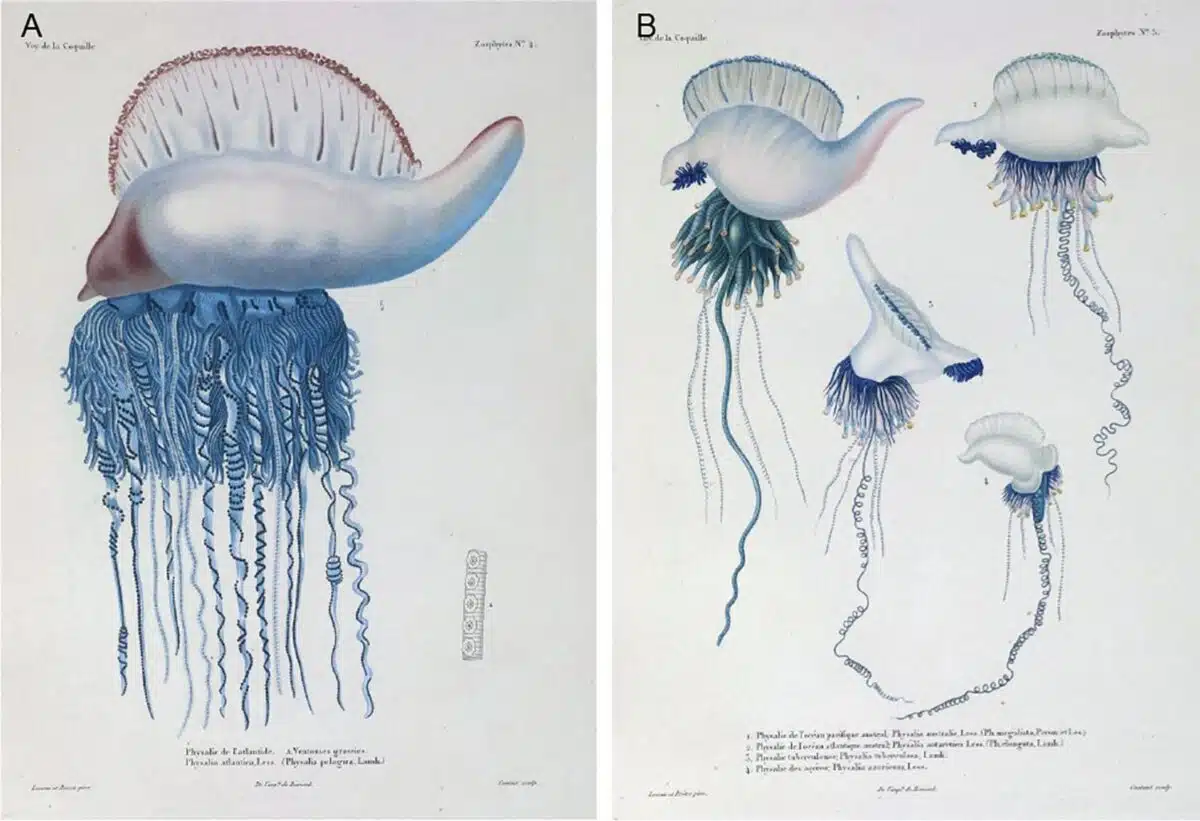

Plates Reproduced From Duperrey (1830) In The “zoophytes” Section Of The French Language Manuscript Written By Lesson. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science

Plates Reproduced From Duperrey (1830) In The “zoophytes” Section Of The French Language Manuscript Written By Lesson. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science

Its discovery has drawn attention not just for what it is, but for what it suggests: warming oceans and shifting currents are driving venomous marine life into unfamiliar waters, with unclear consequences for ecosystems and human safety alike.

New Species, New Territory

Unlike jellyfish, Physalia are not single organisms. They’re colonial siphonophores: clusters of specialized zooids that function as one. Their long, trailing tentacles—equipped with stinging cells—help them capture small fish and zooplankton. And those same tentacles are capable of painful, sometimes dangerous stings to humans.

Until now, Japanese waters were home only to Physalia utriculus, known locally as the “bluebottle,” typically found drifting near Okinawa. But P. mikazuki was found over 2,000 kilometers further north in the Tohoku region—the most northerly record ever for the genus.

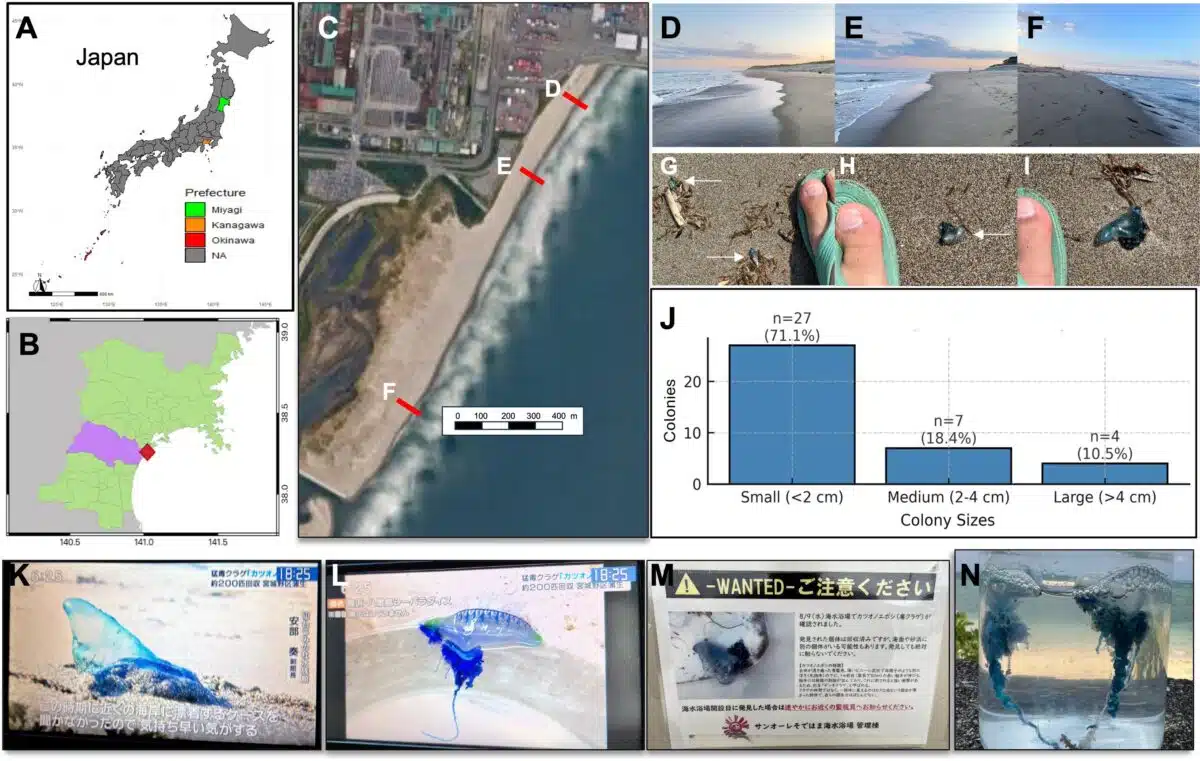

Scientific figure composed of maps, satellite images, photographs of beaches, close-up observations of organisms, and data visualizations documenting observations of Colonies of pleustonic cnidarians (Physalia physalis, Porpita porpita, and Velella velella) along the beaches of Japan. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science

Scientific figure composed of maps, satellite images, photographs of beaches, close-up observations of organisms, and data visualizations documenting observations of Colonies of pleustonic cnidarians (Physalia physalis, Porpita porpita, and Velella velella) along the beaches of Japan. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science

Genetic analysis confirmed it as a new lineage, separate from P. utriculus, P. physalis, P. megalista, and the recently identified P. minuta. Morphologically, P. mikazuki is defined by multiple primary tentacles, unique yellow gastrozooids, and a distinct crest structure. These differences were detailed in the peer-reviewed paper that formally described the species.

“This is the first record of Physalia in Tohoku,” the authors wrote. “The emergence of P. mikazuki in Sendai Bay highlights a significant biogeographical shift.”

Ocean Currents Tell the Story

Using oceanographic modeling based on data from the HYCOM (Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model), researchers simulated the possible migration route of the new species. The results showed a plausible drift path northward from Sagami Bay, carried by shifting surface currents and rising sea temperatures.

Similar patterns have already been observed with the Nomura’s jellyfish (Nemopilema nomurai), a massive gelatinous predator that once rarely appeared near Japan’s main islands but has now become a seasonal threat to fisheries and coastal infrastructure. As with P. mikazuki, its range has expanded in tandem with climate-induced ocean changes.

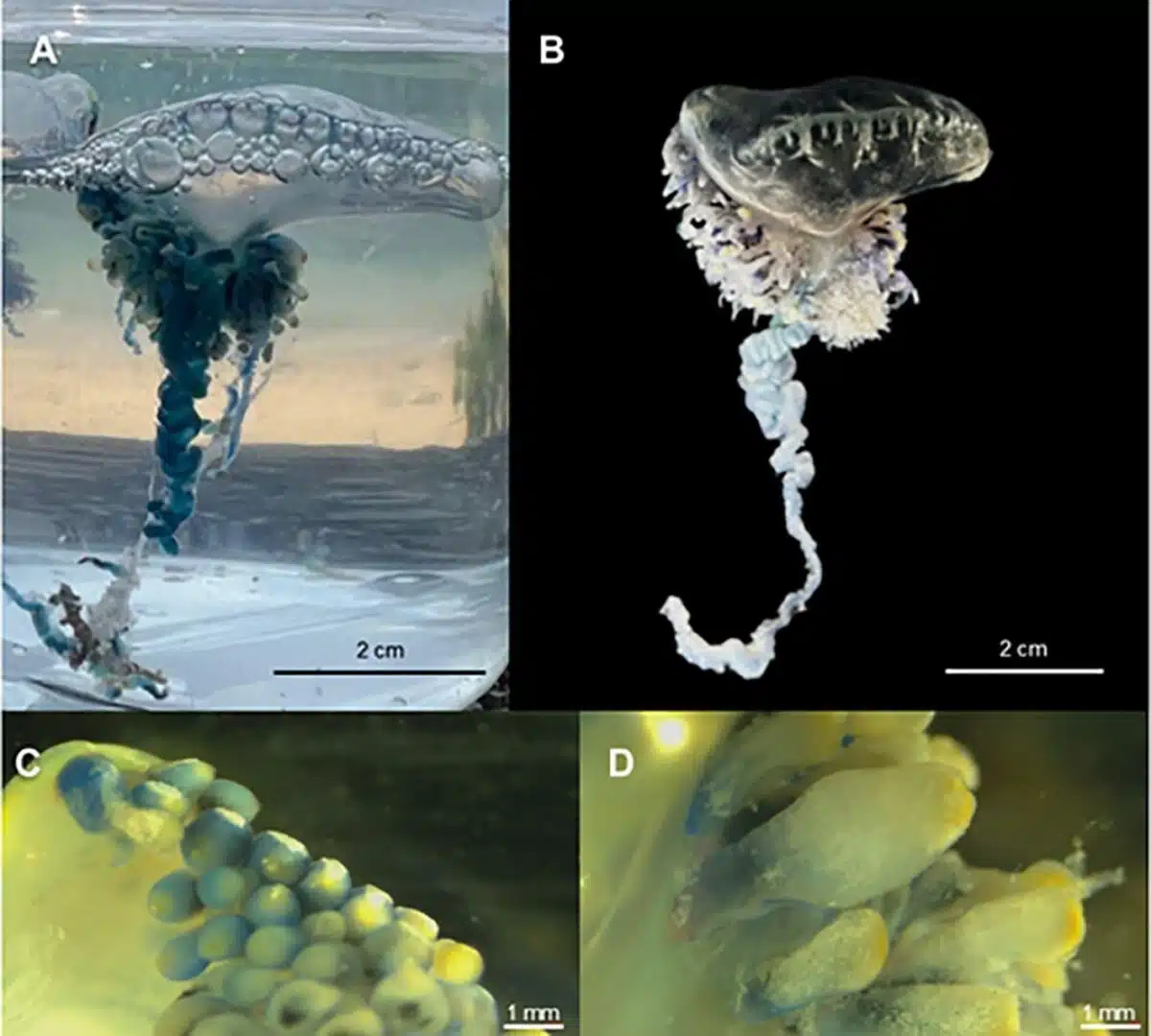

Physalia Utriculus Specimen From Okinawa, Japan. (A) Live individual photographed in seawater shortly after collection. (B) Preserved colony following fixation in 10% buffered formalin, showing contracted pneumatophore and shortened tentacles. (C) Gastrozooid buds from the posterior zone with bulbous morphology and yellow apex. (D) Main zone gastrozooids showing flask-shaped structure with thick texture and diffused yellow pigmentation. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science

Physalia Utriculus Specimen From Okinawa, Japan. (A) Live individual photographed in seawater shortly after collection. (B) Preserved colony following fixation in 10% buffered formalin, showing contracted pneumatophore and shortened tentacles. (C) Gastrozooid buds from the posterior zone with bulbous morphology and yellow apex. (D) Main zone gastrozooids showing flask-shaped structure with thick texture and diffused yellow pigmentation. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science

According to the modeling in the Frontiers study, P. mikazuki’s presence aligns closely with long-term warming trends in the western North Pacific. In particular, the authors cite the increasing frequency of warm-water incursions and unusual wind-driven drift patterns along Japan’s eastern coastline.

The researchers also documented the sudden mass stranding of over 30 P. mikazuki specimens along a 1.5 km stretch of shoreline. Local news coverage, including interviews with aquarium officials, noted that these strandings were unprecedented for the region.

A Global Pattern in Disguise?

While P. mikazuki is newly described, it may not be geographically isolated. Genetic markers associated with the species have turned up in specimens from Mexico and Pakistan, suggesting a broader transoceanic distribution. The team’s DNA analysis places it in a previously unclassified cluster—B2—within the global Physalia phylogenetic tree.

This supports the findings of a 2025 study by Church et al., which identified at least five genetically distinct Physalia species, some of which had been previously lumped under P. physalis without clear type specimens. The existence of P. mikazuki further validates those insights and emphasizes the hidden biodiversity of neustonic (surface-drifting) marine organisms.

In the Popular Mechanics article, the research team points out that P. mikazuki may have remained undetected for so long because it overlaps in appearance with P. utriculus. Its discovery was largely a matter of expert attention to subtle differences.

“These jellyfish are dangerous and perhaps a bit scary to some,” researcher Ayane Totsu said in an official press release quoted by Popular Mechanics, “but also beautiful creatures that are deserving of continued research and classification efforts.”