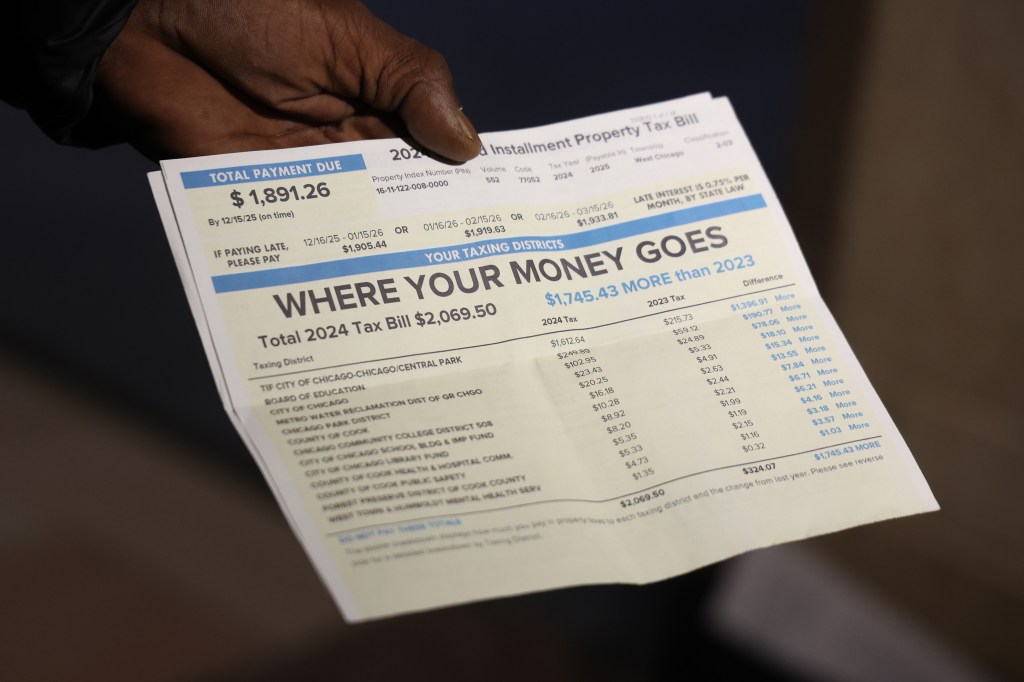

The arrival of a property tax bill never makes for a fun trip to the mailbox, but we sense percolating discontent among Chicagoans and suburbanites when it comes to shelling out thousands of dollars on a semi-annual basis. Even radio hosts are talking about it on the air and we can’t recall when that was previously the case.

Analyses done in the office of Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas (who says she is running for mayor) revealed that typical bills rose the highest in Black neighborhoods on Chicago’s South and West sides, often by eye-watering amounts (133% in West Garfield Park and 82% in Englewood). This was a not a surprise to us. But those were the headlines.

Property taxes and how they are determined are not well understood and, to our minds, the media has not been helping much, often amplifying the erroneous notion that those bills represent some new example of egregious racism or classism when it comes to how governmental expenses are apportioned.

Take, for example, the Chicago Sun-Times report, quoting Lance Williams, a professor of urban studies at Northeastern Illinois University, who told the newspaper that “shifting the tax burden to the city’s poorest residents is a result of bad public policy.”

“It’s unfortunate that this crisis Downtown now has to be felt by Black and Brown neighborhoods,” the paper quoted Williams as saying. “I look at this like robbing from the poor to give to the rich. The poor have to bail out the rich.”

Similar quotes popped up in stories all over town. Once again, “the rich” were taking it on the chin.

What was not in the headlines, though, was the more complicated truth that one big reason these less affluent neighborhoods have seen such massive increases is that the value of property in those neighborhoods has greatly risen. And, if you own property in those neighborhoods and hope to pass on that accumulated wealth to your children, that’s actually good news.

One of the longstanding issues that those in Black and brown neighborhoods in this city have faced, historically, is the difficulty of building equity, or generational wealth, through real estate. If you bought a condo in a more affluent neighborhood in the 1990s, say, you likely were able to sell it for a profit a few years later. But this didn’t apply to all neighborhoods; in several of them, values began to sink, especially during and immediately after the 2008 recession when foreclosure rates shot up. Only now have they recovered. But they’ve come roaring back from those depths.

So what happened? A couple of things. The crippling supply limitation in Chicago real estate (which we’ve written about many times) priced people out of some neighborhoods and they went looking elsewhere. The increase in value also bespeaks of those areas becoming more desirable places to live and even, we think, reflects the growing willingness of young Chicagoans of all races to reject the city’s previous racial demarcations. All of that actually is positive for the city. Rising property values suggests people are taking care of their homes and their blocks. And if they choose to move in the future, the increased equity in their homes gives them a broader set of choices as to where to go, perhaps in retirement.

There are caveats, of course. None of this applies if you do not own your home; higher property taxes means higher rent. The problem with having equity in your home, of course, is that you have to sell the house to capture it (although you can borrow against it) and many people do not want to do that for very good reasons. And the rise in property values since the last assessment started from a very low basis point in many areas.

Still, when Audrey Pierce told the Tribune that her $3,300 tax bill had turned into $7,000 and “I’m getting punished because I cleaned up the block,” the truth is that this is how the system is supposed to work. Pierce owns four buildings on the West Side, the Tribune reported; they now are assessed as being worth a lot more money. This actually isn’t punishment but an indicator of Pierce’s savvy investing skills.

Few see things this way, of course. And those eye-popping bills are not strictly the result of increased property values.

Firstly, they are a consequence of decreased commercial property tax values, especially in Chicago’s Loop. Since the system always gets its money, it’s just a matter of how the bills are apportioned between the two sectors, residential and commercial. Those “rich” commercial property owners are a lot less rich now. As to professor Williams’ comments about the rich bailing out the poor, or Mayor Brandon Johnson arguing that “we have a broken property tax system that essentially forces poor and working people to subsidize the wealthy,” you could also argue the opposite has been the case. If you wanted to be unpopular.

Most importantly, though, the bills for rich and poor are higher because the entities that levy property taxes keep demanding more and more money (as Pappas put it, “spending like drunken sailors”). Chicago Public Schools in particular spends money well beyond the rate of inflation. People right now are tending to focus on assessments and far less on the levy.

As a result, we think that the city is likely to see a lot of people simply not paying their property taxes this time around, a likelihood for which the taxing bodies need to plan. The city of Harvey, which earlier this month declared itself “financially distressed” under Illinois state law and asked the state to take control of its finances, is a cautionary tale there. People not paying property tax bills are a big part of Harvey’s problem.

We’re no fans of a system featuring complex, commercial assessments (which can easily be appealed and thus enrich attorneys) and corresponding residential spikes that make it difficult for people to stay in their own home. As we’ve noted many times, the recent administration of this payment system (including shifting due dates) has been less than desirable, thanks to computer and other snafus. An argument can be made that you should pay annual property taxes based on the value of the home when you buy it (as in California), not on what someone thinks it now is worth. That is, after all, an unrealized gain. And the situation this fall perhaps bespeaks of the need for a property tax cap, so that people can better plan. Although, if we had one, where would that money then come from?

But, to reemphasize our point, at least the value of property has increased in some neighborhoods, making it less attractive to out-of-town flippers hoping to swoop in and then sit on vacant lots, and also allowing families to contemplate a legacy for their kids.

There are two incontrovertible truths. One is that homeowners in this city have a vested interest in commercial property downtown doing well, no matter how much our mayor demonizes business. The other is that for property taxes to go down, the entities that get the money will need to trim their sails.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.