At 422 “fucks” given, Casino premiered as the most profane movie ever in 1995. But Martin Scorsese’s Las Vegas mob epic drew the line at the C-word. That’s right: “Chicago.”

The story was adapted by Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi from the latter’s nonfiction book of the same name. (Pileggi also wrote Wiseguy in 1986 and helped adapt it into 1990’s Goodfellas.) The book tells how the midwest mafia, led by the Chicago Outfit, gripped Vegas in the 70s and early 80s. Working with the Teamsters labor union to grant loans to casino investors, the mob controlled the gambling palaces and siphoned millions in profit. Scorsese’s film adaptation was to follow the Chicagoans who went to Vegas to oversee the operation known as “the skim”: Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, a fastidious, renowned gambler turned casino boss, and Anthony “Tony” Spilotro, a vicious but brilliant gangster who served as the muscle.

Weeks before shooting began, however, studio lawyers began quibbling with the script. The reasons remain murky, but they likely involve the Chicago Department of Law, which was more protective of the city’s media image at the time. Outfit boss Joseph “Joey the Clown” Lombardo was also still active. For fear of a lawsuit, the legal team forced Pileggi and Scorsese to omit the names of the real-life players and their hometown. Always searching for truth in his material, Scorsese resisted before finally relenting.

Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal

Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal

Credit: courtesy Special Collections and Archives, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Robert De Niro as Sam “Ace” Rothstein, an adapted version of Rosenthal

Robert De Niro as Sam “Ace” Rothstein, an adapted version of Rosenthal

Credit: courtesy Universal Pictures

The story remained essentially the same, but Rosenthal became Sam “Ace” Rothstein (Robert De Niro), and Spilotro became Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci). None of the movie was shot in Chicago, and several Windy City–set scenes were transplanted to the desert. The title card at the start of the film changed from “Based on a true story” to “Adapted from a true story.” Mentions of Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, and Cleveland remained in the film, but Chicago was replaced with “back home.”

These redactions obscured what should have been a classic Chicago film about an essential part of the city’s history. Chicago’s past is intertwined with organized crime, but movies almost always focus on the first half of the 20th century: Scarface (1932), The Untouchables (1987), Public Enemies (2009), among others. Unfortunately, the Chicago mob did not end with John Dillinger and Al Capone, and the later stories deserve to be told. “The skim” was one of the most monumental crimes ever perpetrated in the U.S., with the City of Broad Shoulders extending its reach all the way to the Mojave. Chicago deserves to own this history and its portrayal in pop culture.

Pileggi’s book reveals just how much flavor got left on the page.

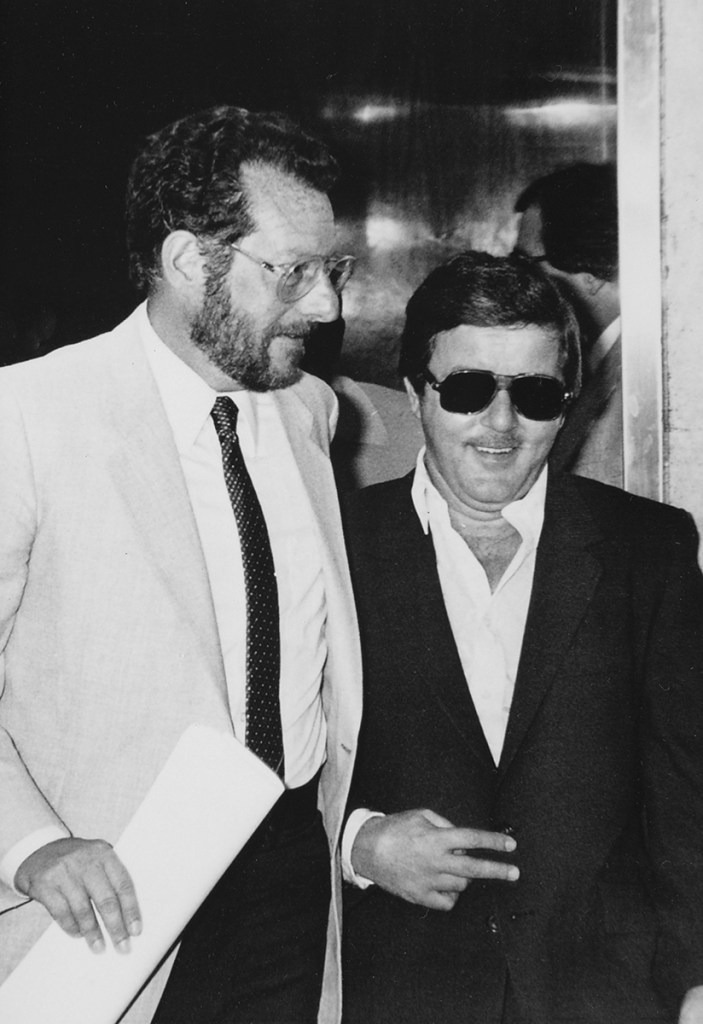

Anthony “Tony” Spilotro (R) with attorney Oscar Goodman

Credit: courtesy Special Collections and Archives, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Joe Pesci as Nicky Santoro, an adapted version of Spilotro

Joe Pesci as Nicky Santoro, an adapted version of Spilotro

Credit: courtesy Universal Pictures

The real Rosenthal was a spindly, ice-eyed blond from the west side. He worked as a clerk and bookie for Chicago gamblers before he could vote and played the odds in the bleachers of Wrigley and Comiskey. After developing a nationwide network of tipsters and a reputation to match, he escaped to Miami and then Vegas. He ran four casinos for the Outfit by the mid-70s. Although De Niro looks nothing like Rosenthal, his commitment to playing the part convinced Rosenthal to contribute to the book and movie.

Spilotro was a fellow west sider. If Pesci was born to play a role, it was this burly, five-foot-five enforcer. The two bore such a resemblance that some casino personnel who had known Spilotro “nearly fainted” in Pesci’s presence, said Pileggi. Groomed for the Outfit at his father’s mob hangout, Patsy’s Restaurant, on the corner of Grand and Ogden, Spilotro slung his weight around town like a bowling ball. The Chicago Sun-Times and Tribune dubbed him “the Ant” sometime after he made his bones carrying out the so-called M&M Murders in 1962, the basis for Casino’s vice torture scene. It happened in Elmwood Park, though, not Vegas.

After joining Rosenthal in Sin City, Spilotro enlisted Chicago pal Frank Cullotta as his street lieutenant. Leading the “Hole in the Wall Gang” burglary crew, Cullotta found it easier to rob homes in Vegas than in Chicago due to the high property walls and lack of neighborliness in the desert town. Frustrated and paranoid over the attention he drew from the Vegas police and media, Spilotro intimated to Cullotta a plan to take over the entire midwest mafia, to become “the pope of the mob,” as Cullotta said in the book. The film only hints at this ill-fated scheme.

Years later, the FBI played Cullotta a tape of Spilotro asking permission to eliminate him. Cullotta turned informant and became an indispensable resource not only for the Bureau but for Pileggi and Scorsese.

On his YouTube channel Mob Vlog, Cullotta remembers Pesci calling him a rat on set. “‘If you ever call me a name like that again, in plain, I will rip one of your eyeballs out of your head,’” Cullotta recalls telling him. “We turned out to be friends.” The former wiseguy also laments the casting, saying, “They don’t pick anybody but from New York, even though this is a Chicago movie.” Cullotta had so many pointers for the actors that he was eventually cast as the main hitman at the end of the film.

From L: Martin Scorsese, Joe Pesci, and Robert De Niro while filming Casino

From L: Martin Scorsese, Joe Pesci, and Robert De Niro while filming Casino

Credit: courtesy Universal Pictures

As is the case with so many Chicagoans, Spilotro and Rosenthal’s lives were dictated—and undone—by food. Spilotro’s weakness was Cullotta’s pizzeria, Upper Crust, where Cullotta claimed to have pioneered the stuffed pie style in Vegas. “As soon as I opened up that fucking pizza joint,” Cullotta recalls in Pileggi’s book, “Tony started coming around too much.” Spilotro was so smitten with the Chicago Italian fare, including beef sandwiches, that he blew his crew’s low profile and jump-started its downfall. Cops started posting up down the street.

Meanwhile, Rosenthal was a ribs guy, and he required them on a strict schedule. As the book recounts, he ordered takeout from the same Vegas restaurant every week at the same time. On October 4, 1982, Rosenthal did just that, then his car blew up. His bomber, still unidentified, knew exactly when and where to carry out the hit attempt. As explained in the movie, the extra metal plate beneath the 1981 Cadillac Eldorado saved Rosenthal’s life, but he fled Vegas months later.

Casino (1995)

R, 178 min. Hulu, Disney+, free on Tubi, wide release on VOD

Thankfully, Casino manages to smuggle in a few references to the Windy City. The Outfit gets a mention. Pesci asks De Niro for the betting line on the “Bears’ game.” But the most precious artifact, the only element of the film that totally escaped the black markers and red pens of Universal’s lawyers, is Pesci’s Chicago accent. We should cherish it.

Perhaps to distinguish the character from his Tommy DeVito in Goodfellas, the actor uses his voice to tell us what “back home” really means. I couldn’t find any information on Pesci’s approach, so I consulted local musician, content creator, and Chicago accent connoisseur Al Scorch.

“Pesci did a pretty good job,” says Scorch. “He strings the words together right.”

Scorch points to the opening voiceover: “He says, ‘I mean he had me, his best friend, lookin’ out for him.’ ‘I-mean-he-had-me’ just becomes one word. All the H’s drop out. The rhythm and cadence are good.” He even begins a sentence with, ‘As a matter of fact.’ I don’t know if that’s common grammar, but it’s really common in Chicago.”

Scorch explains, “The blue-collar Chicago dialect has got a lot of ethnic influence. . . . Irish, Polish, and some Italians drop the same letters. ‘Think’ becomes ‘tink.’” Pesci demonstrates this with phrases like, “He was wit [with] me” and “Trow [throw] her out.”

Scorch also notes the popping sounds on Pesci’s P’s and B’s, called plosives. “In the Chicago accent,” he says, “there will be a lag in the plosive, where you hold the air in your mouth ever so slightly more.”

Pesci hammers the R in “more” and “here” and the nasally A in “pal,” “cash,” and “back home.” He also exchanges TH for D, as in “brudder” (“brother”) and “mudderfucker” (“motherfucker”). And he spits out the classic Great Lakes insult “jagoff” on multiple occasions (not “jerkoff,” as Cullotta made sure).

Pesci’s voice work slips sometimes, particularly during outbursts. Scorch understands: “You kind of go back to the mother tongue when you’re distressed, angered, frustrated.” Pesci also swears much more than the real guy did, according to Cullotta.

If Pesci wanted to maximize the Chicagoness of his performance, he could have

adopted the mustache Spilotro sprouted in his later years. The appearance of a lip caterpillar in the third act of a three-hour movie might have been distracting, but this is nonetheless another act of censorship on the town once named “America’s Most Mustache-Friendly City” by the American Mustache Institute.

Despite the alterations made to the movie, the truth behind Casino still lives within some Chicagoans. Frank Vincent, who plays the fictionalized version of Cullotta, said in 2011, “When I was in Chicago . . . I went into a little restaurant that this little old lady owned, and she said to me, ‘How could you do that to those people? How could you put them in a hole and bury them alive? I knew their wives; they were wonderful people!’”

Those people were Spilotro and his brother Michael, though they were really killed in a Bensenville basement before being deposited in an Indiana cornfield in 1986. They now rest in the Spilotro family plot at Hillside, Illinois’s Queen of Heaven Cemetery. Rosenthal died of an apparent heart attack in Miami in 2008.

The final moments of Casino lament what Vegas has become—corporations took over, squeezing out the personality that made the town special. Scorsese said he viewed this as an allegory for Hollywood, of loss of artistic control and lifeless megaproductions. In stripping Casino of its Chicago roots, he himself was forced to compromise his vision of this film, robbing a classic from a great city’s filmography. But this is a Chicago movie, whether the characters say it or not. Three decades after release, it’s time we took Casino back.

Reader Recommends: FILM & TV

Our critics review the best on the big and small screens and in the media.

Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams is a compelling and beautiful film, but it struggles as an adaptation to live up to its source material.

November 17, 2025November 17, 2025

Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler inspired director Nia DaCosta’s fresh depiction of the titular character’s sexuality and tragedy.

November 17, 2025November 18, 2025

Noah Baumbach unpacks the brittle reality of stardom in Jay Kelly.

November 13, 2025

Sentimental Value offers a clear-eyed view of how complicated regret and reconciliation can be.

November 12, 2025

Predator: Badlands may be unlike any other Predator movie, but it’s all the better for it.

November 12, 2025

Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia gives an unnerving update to Jang Joon-hwan’s 2003 cult masterpiece Save the Green Planet!.

October 30, 2025November 5, 2025