Researchers at the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences (iTHEMS) in Japan recently accomplished something truly unprecedented. With the help of colleagues from the University of Tokyo and the Universitat de Barcelona, the team conducted the world’s first Milky Way simulations that accurately represented more than 100 billion stars over 10,000 years. The simulation not only represented 100 times more individual stars than previous models, but was also produced 100 times faster.

The simulation was accomplished by combining 7 million CPU cores, machine learning algorithms, and numerical simulations. The resulting model represents a breakthrough for astrophysics, supercomputing, and AI development, and provides astronomers with a means for studying stellar and galactic evolution on a massive scale. The team’s research was presented in a paper titled “The First Star-by-star N-body/Hydrodynamics Simulation of Our Galaxy Coupling with a Surrogate Model,” published in the *Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis* (SC ’25).

Simulations of the Milky Way that capture dynamics down to individual stars are a means of testing theories of galactic formation, structure, and evolution, which they can then compare to astronomical observations. Astronomers have been working for decades to develop simulations of increasing complexity, which is rather challenging. To accurately capture all the forces at work. These include gravity, fluid dynamics, supernovae, element synthesis, and the influence of supermassive black holes (SMBHs), all of which occur on different scales.

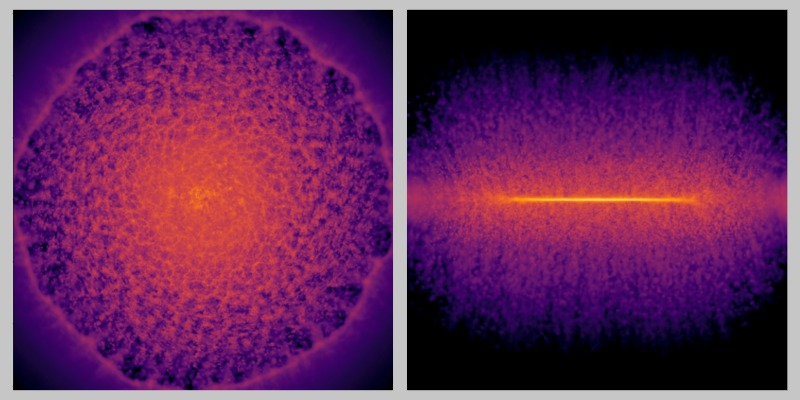

*Head-on (left) and side-view (right) snapshots of a galactic disk of gas. Credit: RIKEN/iTHEMS*

*Head-on (left) and side-view (right) snapshots of a galactic disk of gas. Credit: RIKEN/iTHEMS*

So far, scientists have not had the necessary computing power to model galaxies at this level of detail and complexity. The current mass limit is about one billion solar masses, less than 1% of the stars in the Milky Way. What’s more, it would take state-of-the-art supercomputing systems about 315 hours (over 13 days) to simulate 1 million years of galactic evolution – a little more than 0.00007% the age of the Milky Way (13.61 billion years old and counting) – and over 36 years to simulate the desired 1 billion years.

As a result, only large-scale events can be accurately simulated, and simply adding more supercomputer cores doesn’t resolve these issues. Not only does it require massive amounts of energy, but efficiency decreases as more cores are added. To address this, Hirashima and his team employed an AI shortcut in the form of a machine learning surrogate model that did not use resources that powered the rest of the model. This model was trained on high-resolution simulations of a supernova, allowing it to predict how these explosions will affect the surrounding gas and dust they expel 100,000 years after the explosion takes place.

When combined with physical simulations, the team was able to model the overall dynamics of a Milky Way-sized galaxy and small-scale stellar phenomena simultaneously. Said Hirashima in a RIKEN press release:

I believe that integrating AI with high-performance computing marks a fundamental shift in how we tackle multi-scale, multi-physics problems across the computational sciences. This achievement also shows that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become a genuine tool for scientific discovery—helping us trace how the elements that formed life itself emerged within our galaxy.

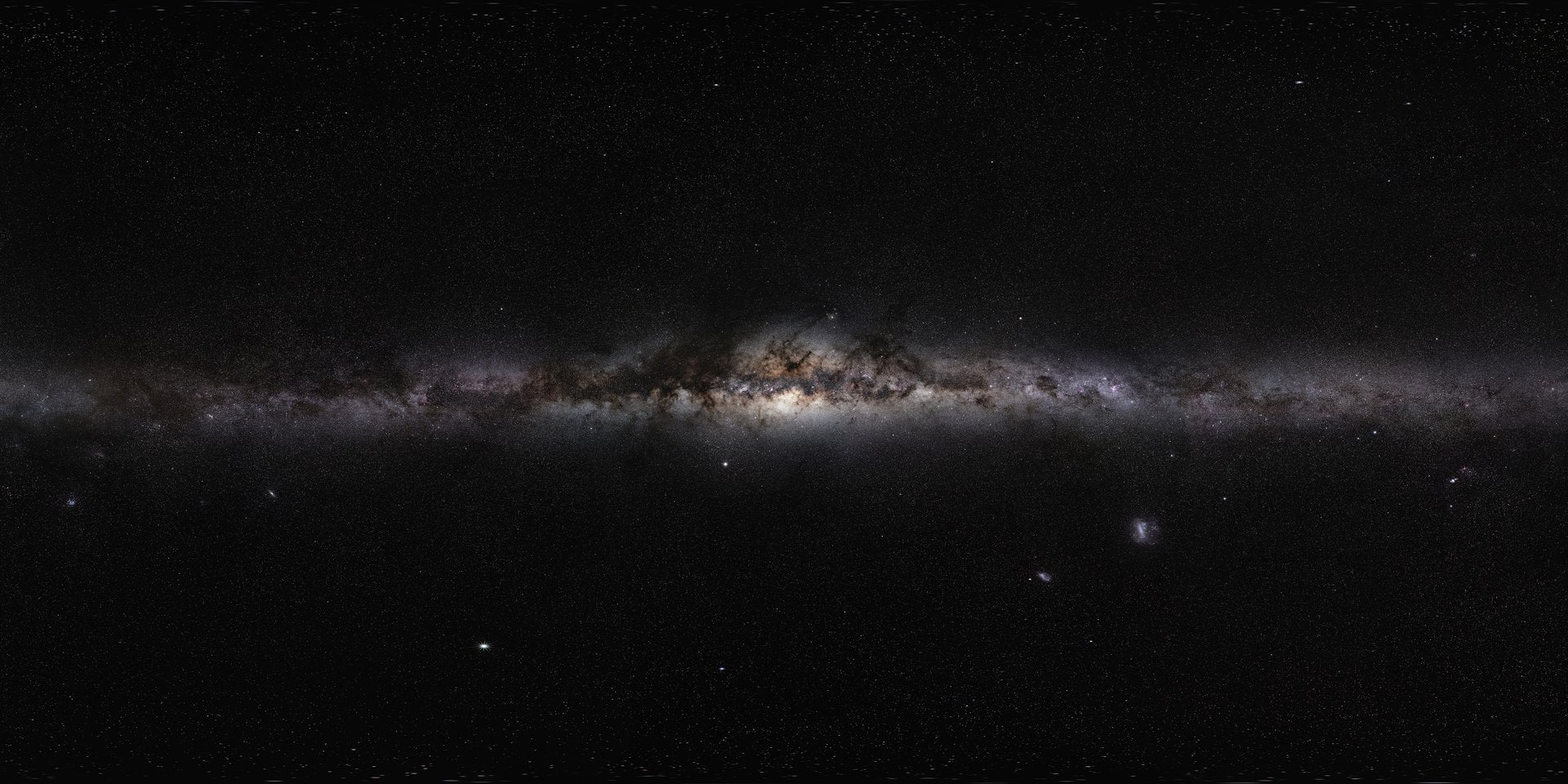

*The night sky above the Paranal Observatory in the Atacama Desert, Chile. Credit: ESO/Y. Beletsky*

*The night sky above the Paranal Observatory in the Atacama Desert, Chile. Credit: ESO/Y. Beletsky*

The team then verified their model’s performance through large-scale tests on the Fugaku and Miyabi Supercomputer Systems at the RIKEN Center for Computational Science and the University of Tokyo (respectively). The tests showed that the team’s new method could simulate star resolution in galaxies with more than 100 billion stars, but could simulate 1 million years of evolution in just 2.78 hours. Not only does the method allow individual star resolution in large galaxies with over 100 billion stars, but simulating 1 million years only took 2.78 hours.

At this rate, 1 billion years of galactic history could be simulated in just 115 days. These results provide astronomers with an invaluable tool for testing theories about galactic evolution and how our Universe came to be. It also demonstrates how the inclusion of surrogate AI models could improve advanced simulations by reducing the time and amount of energy required. Beyond astrophysics, this “AI shortcut” approach could enable other complex simulations that call for large and small-scale factors, such as meteorology, ocean dynamics, and climate science.

Further Reading: RIKEN