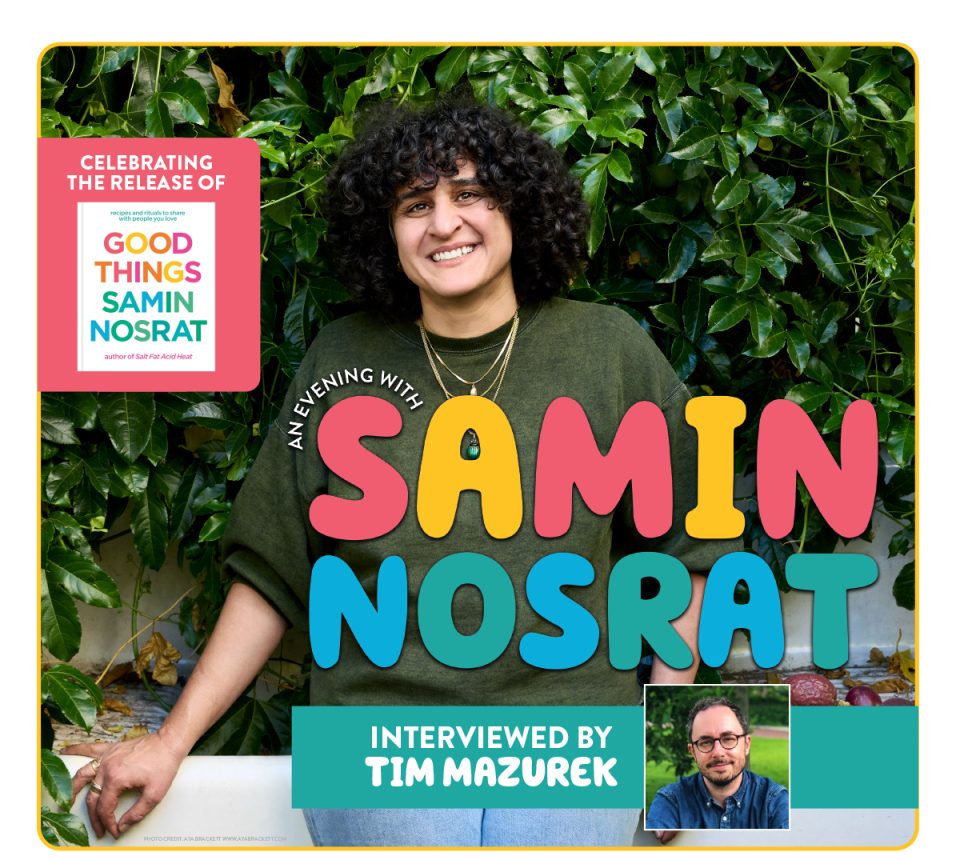

Upon receiving chef Samin Nosrat‘s newest book, Good Things, it was clear that the cultural phenom born with her first project, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, was here to stay. Alongside cooking basics and creative concoctions, the new book advises readers not only on making delicious recipes, but on the importance of who you’re cooking for. In his introduction, Chicago Humanities co-creative director Michael Green shared that the humanities help us understand ourselves. Nosrat’s visit reminded the audience of everything we have to give each other.

The author’s discussion with longtime friend Tim Mazurek included live projected captions, which helped the audience keep up with the discussion—I went home with plenty of helpful quotes for the next time I need a role model for resilience. Nosrat talked about the difficulty of turning around in the face of her debut success in 2017, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, and producing a follow-up book of recipes and life lessons. She described the burden of suddenly becoming a public figure, and Mazurek chimed in to call her “America’s sweetheart.” The chef would sign books for three hours after an event, going home from press engagements completely depleted. She had wanted to honor the parasocial relationship she has with fans, saying, “I felt it was my responsibility to show up for the attention and the excitement.” It was her job to “be joyful and sell books,” but she was struggling.

By 2020, Nosrat just wanted to stay home and garden, and with the onset of the pandemic, her wish came true. But staying home didn’t prove effective against mental exhaustion, and she still had the mindset that if she could just work hard enough, then she would be happier. But what really helped was coming back into a community with people she valued.

Nosrat’s book, Good Things. Photo credit: Row Light.

Nosrat’s book, Good Things. Photo credit: Row Light.

As a cook, Nosrat is methodical and efficient. But as a writer, efficiency won’t necessarily help you create something you’re proud of. Unlearning and healing from lifelong perfectionism, introducing a sense of playfulness, and learning to trust her intuition became important factors in Nosrat’s reprogramming. She also learned to let others make their own mistakes with cooking. She told the audience, “Everybody is an expert in food. You have a lifelong relationship with it.” There’s even a chapter in Good Things called “The Problem with Recipes.”

If you cook something enough, she shared, it becomes a part of you. Like Nosrat’s first book outlining the basic four elements of any delicious recipe, this project cracks open the unapproachable reputation around cooking, much like one of my favorite movies, Ratatouille, which uses the maxim “Anyone can cook.” In the forced proximity of the pandemic, Nosrat and her neighborhood community created new rituals around food, celebrating both milestones and weekly dinners together that the chef describes as a kind of church. They were not all chefs, and Nosrat was trying, and failing, over and over to find the perfect recipe for Al Pastor tacos. Still, these rituals helped craft the thesis of her new cookbook.

Good Things is dedicated to re-answering the question, “What is a good life?” When asked if she gets tired of cooking, Nosrat said yes. Her advice for rediscovering joy in an activity is to slow things down—to stop multitasking and settle into the quiet. She reintroduces curiosity toward cooking, which in turn brings renewed appreciation. Despite the book’s culinary prowess, it really does feel like a neighbor or friend giving you advice, showing you albums full of their favorite meals and memories with the people they love. It breaks down how to cook almost any vegetable and provides substitutions at every turn, so you can make changes to any recipe according to the available ingredients. Of course there are some challenging and complicated dishes, but she writes with an accessible warmth and familiarity that recalls the oral tradition of passing recipes down through generations. As one chapter title states, “Good things are better shared.”

Sharing this book is like visiting a community garden and finding the piece of fruit that looks best to you. As many of us know, the holidays are a heightened time for emotions, especially when it comes to nostalgia, traditions, and familial relationship dynamics. Nosrat’s book might be just the reminder we need to slow down and find gratitude in connection, while making the chef’s personal recipes our own.

Chicago Humanities is located at 500 N Dearborn St, Chicago. You can find their schedule for the Spring 2026 Humanities Festival on the website.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider supporting Third Coast Review’s arts and culture coverage by making a donation. Choose the amount that works best for you, and know how much we appreciate your support!

This coverage was made possible by a promotional invitation. Our opinions and editorial choices remain entirely our own.