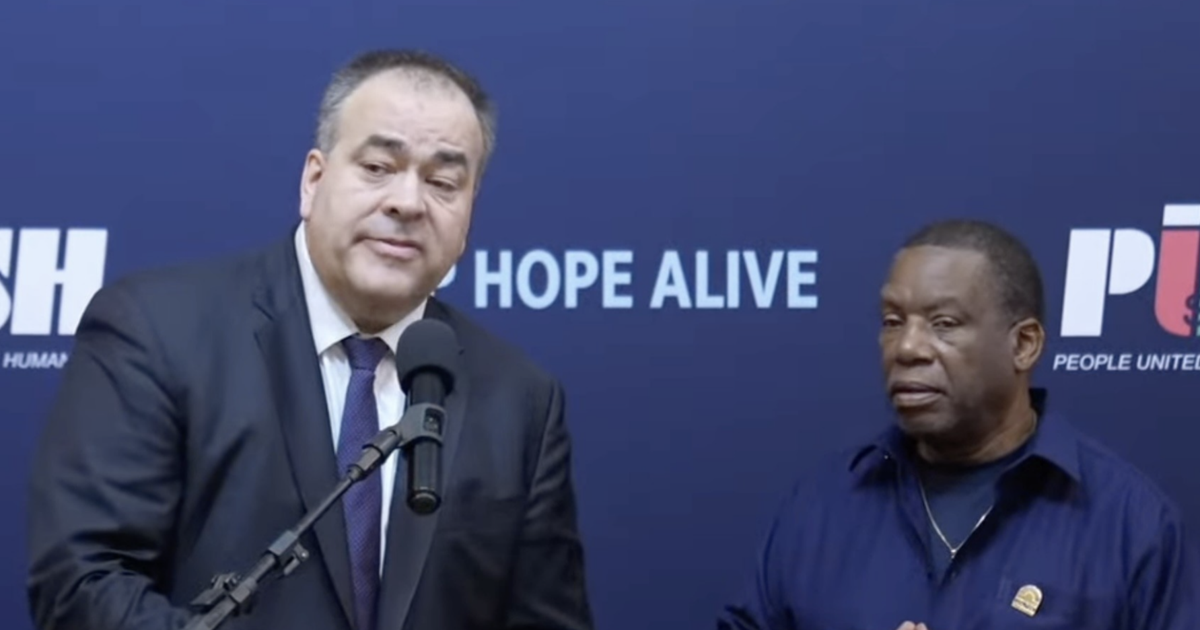

Property tax bills that have surged across some of Chicago’s South and West Side neighborhoods sparked a recent heated exchange at Rainbow PUSH headquarters, where Cook County Assessor Fritz Kaegi and Board of Review Commissioner Larry Rogers Jr. publicly blamed each other for steep increases.

In recent weeks, homeowners have grappled with tax bills that have jumped from 50% to more than 100% in some neighborhoods, according to a report released by Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas’ office.

The median property tax bill for a Chicago homeowner increased 16.7% since last year, the largest percentage increase in 30 years. In Hyde Park, the increase was less severe, 8.6%, but in Woodlawn it was much more pronounced, at 33.3%.

Speaking before an audience of frustrated residents during a Nov. 22 forum at Rainbow PUSH, 930 E. 50th St., Kaegi argued that reductions granted by the Board of Review to downtown commercial properties shifted an estimated $700 per homeowner onto residential bills. Those tax bills come due Dec. 14.

“Guess where that came from?” Kaegi said, pointing to what he called inappropriate reductions granted to Loop hotels, office towers and data centers on appeal at the Board of Review.

Kaegi said those reductions were out of step with current market conditions. While hotels and offices saw large pandemic-era vacancies that depressed values in 2021, he argued, the Board of Review continued granting large reductions even as occupancy recovered. When commercial assessments fall, a greater share of the tax levy shifts to homeowners.

Pappas’ report shows that commercial properties in the Loop saw their collective tax bills fall by $129 million. Meanwhile, homeowners in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods absorbed dramatic increases. West Garfield Park’s median homeowner bill more than doubled, rising from $1,482 to $3,448. North Lawndale saw a similar spike, from $1,905 to $3,791.

The assessor’s office determined that homeowners’ share of property value in Cook County was 49% for last year’s Chicago reassessment, while commercial and non-residential properties made up 51%. But after Board of Review appeals, the homeowner share rose to 54%.

“The biggest, most famous, nicest hotels downtown — their tax bills fell. And you cannot tell me that any hotel today is doing worse than it was in 2021, when these hotels were empty,” Kaegi said. “We in North Lawndale, in West Garfield Park, here on the South Side, we’re picking up the tab for them.”

But Kaegi also said some of the sharp increases in South and West Side neighborhoods reflect real growth in property values. Sales prices in many neighborhoods have climbed significantly since Chicago’s last reassessment in 2021, driven partly by community groups flipping vacant lots and rehabbing homes, and partly by an influx of outside investors and speculators.

The median sales price of a residential property in central Englewood, for example, rose from less than $26,000 between 2016 and 2018 to $95,000 between 2022 and 2024, according to a September analysis by the Illinois Answers Project and the Tribune.

“People who stuck it through the housing crisis all those hard years when they were underwater on their mortgage,” Kaegi said, are finally now “getting a return on their investment.”

He also told property owners to file appeals if they believe their properties were overvalued.

“If we overestimated the value of your house, especially if it hasn’t been renovated … that’s the kind of thing that we want to hear about in your appeals,” he said.

A condominium building in Hyde Park, 5200 S. Drexel Blvd., Nov. 30, 2025.

Marc C. Monaghan

Rogers, however, accused Kaegi of “bamboozling” residents by creating the problems he then asks the Board of Review to fix.

“What he’s telling you to do is to come to me to fix his mistakes, while simultaneously telling you I’m the reason that your bill is high,” Rogers said. “Are we going to believe and be bamboozled by that BS anymore?”

Rogers cited an August 2024 Illinois Answers Project and Tribune investigation that found that Kaegi’s office missed at least $444 million in market value, leaving money off the tax rolls and shifting the burden onto other property owners. He also accused Kaegi of over-assessing properties in Black neighborhoods, saying the assessor “thinks he’s the overseer in our communities.”

“He’s raising the values in our communities, driving us out, living in Oak Park, while he says I’m from Kenwood, I’m your neighbor,” Rogers said, referencing Kaegi’s upbringing in the neighborhood.

The Board of Review commissioner defended his office’s appeals process as evidence-based and transparent, noting that all decisions are posted publicly online. He said when the assessor overvalues properties and owners appeal with documentation like appraisals or MLS listings, the board grants reductions in more than 70% of cases.

Rogers challenged Kaegi to issue certificates of error for entire communities where assessments spiked dramatically, rather than forcing individual homeowners to appeal one by one.

“If he sends me a certificate of error acknowledging that he increased West Garfield Park and Lawndale by 40, 50, 60%, we will honor it,” Rogers said. “We will accept it.”

Kaegi countered that reports from both Pappas and Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle’s office supported his position. Pappas found that 90% of reductions granted on appeal were for commercial properties, mostly by the Board of Review. A Preckwinkle-commissioned study found the board reduced commercial assessments more than 15% below appropriate levels in two of the three years examined, shifting the burden onto homeowners.

A separate report published this spring by the treasurer’s office found that South and West Side homeowners have borne the brunt of the appeals system, with nearly $2 billion in property taxes shifted from commercial owners to homeowners due to Board of Review reductions given between 2021 and 2023. The report also found lower-income homeowners are less likely to appeal for relief.

Earlier this year, Kaegi’s office pushed a proposal that would give low- or fixed-income homeowners whose bills spiked by 25% or more an income tax credit to help cover part of the increase. The bill stalled in Springfield, partly due to its roughly $200 million price tag.

Kaegi also highlighted his ethics policy of refusing campaign donations from property tax appeals lawyers, urging the Board of Review commissioners to adopt the same standard. The county’s inspector general recommended such a ban in 2015.

“It is a critical vulnerability that you’re taking donations from the people who provide you with this evidence,” Kaegi said.

Rogers, who was first elected in 2004 and most recently reelected in 2024, accepted a $1,500 donation from a local property tax law firm just last month, and many of his largest contributors have been downtown real estate law firms, according to Reform for Illinois’ Sunshine database. Kaegi attempted to oust him in that election cycle by funding his opponent, Larecia Tucker.

Kaegi, on the other hand, is up for reelection next November. The wealthy former mutual fund manager and the son of a longtime University of Chicago professorlargely self-funded his 2018 and 2022 campaigns. In March, he donated more than $5.6 million to his latest reelection campaign, according to Reform for Illinois’ Sunshine database.

Rogers has given $50,000 to one of Kaegi’s primary challengers, Dana Pointer. She also happens to be the director of outreach in Rogers’ office.

Rev. James Meeks, who moderated the forum, proposed a solution: Rainbow PUSH would organize community days at the assessor’s office for West Garfield Park, Englewood and other hard-hit neighborhoods to help residents seek reductions.

“When the elephants collide, the people get trampled,” Meeks said. “We need to be able to simplify it so that we can understand it. This won’t be our last session on taxes. This is our first session on taxes, but we’re going to stick with something until we get it straight.”