CHICAGO — Just days after Operation Midway Blitz began, an ICE agent fatally shot Silverio Villegas Gonzalez, a 38-year-old man, during a traffic stop in suburban Franklin Park.

The Department of Homeland Security later claimed one agent was “seriously injured” after being dragged by Villegas González’s car as he tried to flee, but body-camera footage showed an agent telling a Franklin Park police officer his injury was “nothing major” shortly after the shooting. Neither of the agents involved were wearing a body camera at the time of the shooting.

Two weeks later, federal agents busted doors and windows of a South Shore apartment building and arrested 37 people. “Some of the targeted subjects are believed to be involved in drug trafficking and distribution, weapons crimes and immigration violators,” Department of Homeland Security officials said in a statement the day after the raid. The agency soon released a slick, heavily edited video, claiming the building was frequented by members of Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

Federal prosecutors have not filed criminal charges against anyone who was arrested during the South Shore raid. A ProPublica investigation found there was little to support the government’s claims — and at least one of the two men accused of being a Tren de Aragua member has no criminal record.

As Trump’s Operation Midway Blitz swept through Chicago this fall, federal leaders and agencies issued statements and social media posts that contradicted what reporters and witnesses saw on the ground. They’ve attempted to discredit journalists even after a federal judge ruled that Border Patrol chief Gregory Bovino, a face of the operation, lied and the federal government had deceived the public and made false claims.

Experts who study propaganda and state media say the pattern goes beyond spin. In press releases and social media posts, the Department of Homeland Security has built a narrative meant to project control and valorize its agents, the experts said. At the same time, it has cast protesters and bystanders as threats or obstacles.

The agency’s language mirrors tactics used by governments to justify repression at home and abroad, rewriting events as they happen to shape how the public understands and digests them, they said.

“They’re working very hard to make the American people the enemy because they disagree with them,” said Ed Yohnka, director of communications and public policy for the ACLU of Illinois. “And that should worry all of us.”

It’s an approach that obscures what’s happening in Chicago — and raises questions about how far the federal government will go to control the story.

“This is one of the things that I think is very dangerous,” said William Nickell, a University of Chicago professor who studies propaganda and media. “At certain points, a narrative can become what people buy into, even if it’s counterfactual. And once that happens, it can distort thinking and justify actions that would otherwise be unacceptable.”

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment.

When The Government Uses Propaganda

The U.S. government has been involved with propaganda since “at least World War I,” said Robert Pape, a professor of political science at the University of Chicago.

It started with Woodrow Wilson when he created a government board that directed committees to run propaganda efforts in the United States to drum up support for going to war against Germany.

Historically, this propaganda has been directed against external enemies, Pape said.

But Chicago has become the target of federal propaganda, with local officials, including Gov. JB Pritzker, saying the government was “invading” the city and waging a “war.”

On social media, the Department of Homeland Security has turned immigration enforcement into a cinematic campaign, using drone footage, songs and tough-on-crime slogans that depict Chicago as a city under siege.

In September, Bovino announced on X that Operation At Large — Border Patrol’s counterpart to Midway Blitz — had arrived with a video featuring footage of agents driving and agents on the Chicago River. Another video soon after showed patrol boats circling Trump Tower as part of what the area’s alderman called a “photo op.”

Dan returns to his apartment unit, which was completely ransacked and had items left behind that were not his — at 7500 S. South Shore Drive in South Shore on Oct. 1, 2025. The apartment building was raided by federal agents the morning before. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Dan returns to his apartment unit, which was completely ransacked and had items left behind that were not his — at 7500 S. South Shore Drive in South Shore on Oct. 1, 2025. The apartment building was raided by federal agents the morning before. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

A video posted by the White House Oct. 8 declared that “Chicago is in chaos, and the American people are paying the price.” The video includes a voice-over of President Donald Trump with flashing lights and agents in tactical gear. News service AFP, or Agence France-Presse, fact-checked the video and found most of the footage was taken in Florida, Texas and South Carolina, not Chicago.

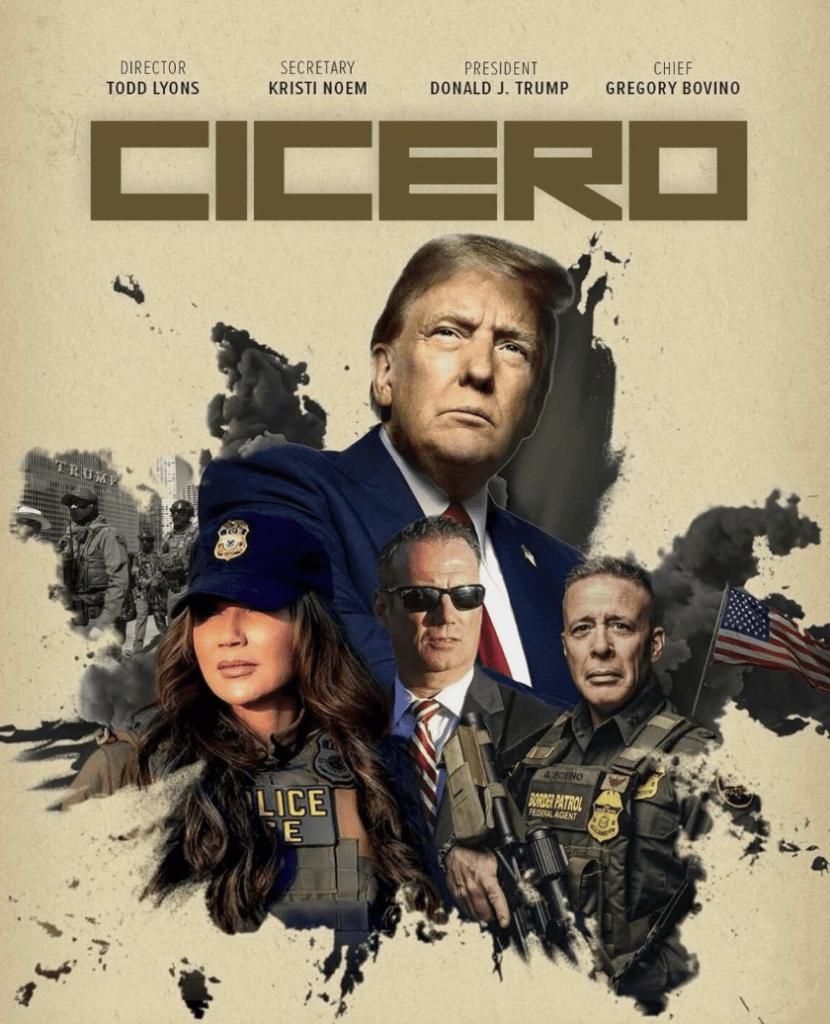

A movie poster-like image shows President Donald Trump, Secretary Kristi Noem, Director Todd Lyons and Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino. Credit: Department of Homeland Security

A movie poster-like image shows President Donald Trump, Secretary Kristi Noem, Director Todd Lyons and Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino. Credit: Department of Homeland Security

And on Oct. 24, the Department of Homeland Security posted a movie poster-like image of Trump, Bovino, agency director Todd Lyons and department Secretary Kristi Noem with the fake title, “Cicero.” In the post, the agency wrote that Oct. 22 had been one of the “most violent” days faced by agents and that “rioters” would not slow agents. But on that day, agents pepper-sprayed at least one person and detained several people, including at least two U.S. citizens, in Little Village and suburban Cicero.

The federal government’s videos and photos have been cinematic and triumphant, showing agents with weapons and people being handcuffed.

“They really are engaged in a rather straightforward propaganda campaign,” Pape said. “They might call it an information campaign, but there’s no real difference between the two. It’s all about using tailored information to persuade audiences of certain points.”

Pape, head of The Chicago Project on Security & Threats, said the federal government’s social media posts mirror the strategic building of narrative often seen in extremist groups. The videos highlight “heroic” acts by agents, portray raids as cleanly executed and frame anyone obstructing operations as dangerous.

“The way the videos are produced, they took a page out of Hollywood’s book,” Pape said. “If you look on the DHS website, they’re doing a lot to depict their ICE agents as the heroes in the story.”

Pape said that the effect goes beyond making agents look good: The curated imagery and framing can shape public perception in ways that make the public more likely to see harsher enforcement as justified. Sympathetic audiences exposed to the videos can become more accepting of the aggressive strategies, even when the operation has “unseen human costs,” Pape said.

Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino stands at the front as dozens of neighbors confront federal agents in Cicero just outside Little Village as the agents conduct immigration raids in the area on Oct. 22, 2025. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino stands at the front as dozens of neighbors confront federal agents in Cicero just outside Little Village as the agents conduct immigration raids in the area on Oct. 22, 2025. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

The Department of Homeland Security’s flashy video of the raid in South Shore shows agents going through the building with their guns drawn and leading away men whose hands are zip-tied. It does not show the children who, despite them being U.S. citizens, agents detained for hours, nor does it show how building residents returned to their units to find them ransacked and their property stolen after the raid.

Controlling the narrative in this way is less about persuading neutral observers than about hardening divisions, Pape said.

“The DHS Twitter campaign is highly unlikely to be persuasive to ordinary residents in Little Village or Pilsen,” Pape said. “But it will tighten support around an already sympathetic audience, particularly people who might already back Trump, while producing defiance among those communities targeted by these operations.”

Trump has for years used social media and public appearances in this way to target Chicago, a Democratic stronghold, making false claims about its leaders and crime in an effort to justify federal intervention — like calling in the National Guard.

“Chicago is a hellhole right now,” Trump said at a press conference in September, saying that the city is the “murder capital of the world.”

Chicago is not the murder capital of the world, and violent crime rates here have been falling, according to data from the Chicago Police Department and FBI. But when Trump uses that language, which is then reemphasized on the federal government’s social media pages, it’s used as a message to people who are sympathetic to his own cause, Pape said.

“In that sense, the propaganda acts as a wedge,” Pape said. “It reinforces loyalty on one side and defiance on the other.”

When Discrediting Journalists Becomes Part Of The Strategy

For longtime civil liberties observers, the Trump administration’s handling of the press and, by extension, the public during Operation Midway Blitz is not just unusual — it’s unprecedented.

Department of Homeland Security spokespeople have repeatedly refused to answer basic questions about who agents have arrested. Officials have tried to ignore Freedom of Information Act requests, leading Block Club Chicago and others to sue for records. Homeland Security and its leaders have issued statements that seemingly contradict what witnesses and reporters say happened. A federal judge questioned and outright accused Bovino and federal officials of misrepresenting facts.

“This is nothing any of us have ever seen before,” Yohnka said. “It reflects a disdain both for journalists and for the public. They repeatedly misrepresent facts, double down on falsehoods and seem uninterested in getting anything right.”

Manifestantes se enfrentaron con la Policía de Illinois, la Policía de Broadview y agentes del Alguacil del Condado Cook durante una “fiesta de disfraces” en el centro de procesamiento de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE) de Broadview el 1 de noviembre de 2025.

Manifestantes se enfrentaron con la Policía de Illinois, la Policía de Broadview y agentes del Alguacil del Condado Cook durante una “fiesta de disfraces” en el centro de procesamiento de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE) de Broadview el 1 de noviembre de 2025.

Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

Yohnka said what stands out is how quickly federal leaders’ “official version” of a story collapses.

On Oct. 4, federal agents shot 30-year-old Marimar Martinez in Brighton Park after they were “rammed by vehicles and boxed in by 10 cars,” Assistant Homeland Security Secretary Tricia McLaughlin and Chicago police said at the time. The agents left their cars and were “forced to … fire defensive shots” at Martinez, McLaughlin said.

Martinez was charged with assaulting, impeding and interfering with a federal law enforcement officer. But body-camera footage contradicted the Department of Homeland Security’s version of events, and the charges were dropped Nov. 20.

During an Oct. 30 news conference, Noem said no U.S. citizens had been detained during Midway Blitz. However, dozens of U.S. citizens had been detained, including two citizens during a raid that she was there for in suburban Elgin.

“Their first story always falls apart, usually within hours,” Yohnka said. “They’re trying to create a narrative that simply doesn’t exist. They believe they can convince a broader public, especially outside Chicago, that something is happening here that isn’t.”

That narrative only holds if journalists can be discredited.

For the Trump administration, discrediting journalists is not a side effect of the operation, but a part of it, experts said.

“This is a broader effort to essentially criminalize immigration reporting,” said Seth Stern, director of advocacy at Freedom of the Press Foundation, who lives in suburban Evanston. “They’re lying constantly, and they’re attacking the press constantly. Those two things feed each other.”

But Chicago’s media landscape has complicated that plan.

When Chicago Tribune reporter Gregory Pratt reported on where federal agents were operating, McLaughlin took to X to accuse him of interfering with their enforcement while neighbors and other reporters supported him.

“You can’t discredit community media the way you can discredit CNN,” Stern said. “People know their local reporters. They see them on the street. They rely on them. That makes it harder for the administration to control the narrative. And they know it.”

Shades Of The Soviet Union

Nickell, a professor in the Department of Slavic Languages & Literature at UChicago, said the Trump administration’s messaging strategy in Chicago resembles a familiar pattern from modern authoritarian systems — most notably, Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Nickell noted that Putin consolidated control over Russian media by reorganizing the country’s once-independent outlets under oligarchs loyal to the Kremlin, ensuring that nearly all political discourse flowed through state-approved channels. What emerged was a system where the government could “set the terms of reality,” he said.

Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino hops into a truck after exiting the Federal Building on Oct. 28, 2025. Credit: Arthur Maiorella for Block Club Chicago

Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino hops into a truck after exiting the Federal Building on Oct. 28, 2025. Credit: Arthur Maiorella for Block Club Chicago

The United States isn’t there, but the strategy feels familiar, Nickell said. In Russia, Putin’s consolidation started with individual and independent outlets being pressured, bought out and steered by loyal oligarchs until only a few dissenting voices survived.

Here, Trump has personally urged ABC to fire Jimmy Kimmel, called for NBC to fire Seth Meyers and watched as the billionaire owners of the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times — both of whom killed planned endorsements of Kamala Harris after internal pushback — faced accusations that their decisions were meant to avoid angering him. CBS canceled The Late Show with Stephen Colbert despite it being the top show in late night. Though the network claimed the show was canceled for financial reasons, the move came after Colbert criticized a $16 million settlement Paramount paid Donald Trump.

Earlier this year, the Trump-approved sale of Paramount helped pave the way for Bari Weiss — a vocal critic of legacy outlets — to become editor in chief of CBS News.

To Nickell, the tactic echoes an even earlier era of state-driven narrative control. In the Soviet Union of the ’30s, the government’s constant storytelling and ideological messaging reshaped what people accepted as true, he said.

“What we saw in the ’30s in the Soviet Union was people actually beginning to report on their neighbors,” Nickell said. “Soviet power became so infectious that it really distorted people’s thinking.”

Nickell sees troubling echoes of that now.

“That’s where narrative can become really dangerous,” he said. “Because once somebody, like Donald Trump in this case, is effective at instilling an idea in people’s minds, the consequences can be really drastic.

“We thought we had institutions — the courts, the press — but we see a systematic attempt to gain control of all of these. … There’s more erosion of a sense of agency than I imagined I would experience in my lifetime in the United States. I’m not sure we actually have the power to stop it.”

Like the media consolidation under Putin, the Trump administration’s control over messaging allows it to “set the terms of reality,” Nickell said.

“The media environment we’re in has created a platform, and that’s why it’s been so important to Trump that he has access to these platforms,” Nickell said. “He’s been so savvy about using social media. … He would just say whatever he wanted people to think, and he seems to understand that in this current situation, proof doesn’t really matter.”

U.S. Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino and agents gather for a photo at Millennium Park and the Cloud Gate after the winter storm overnight in Chicago on Nov. 10, 2025. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

U.S. Border Patrol chief Greg Bovino and agents gather for a photo at Millennium Park and the Cloud Gate after the winter storm overnight in Chicago on Nov. 10, 2025. Credit: Colin Boyle/Block Club Chicago

One Final Spin For The Road

A few days before Bovino left town, he and dozens of his commandeers stood on the snowy steps at Millenium Park, firearms in hand, and mocked the predominantly Mexican-American neighborhood Little Village while posing for a photo in front of the city’s iconic Bean.

Bovino posted the photo on X, with agents’ faces blurred, and claimed that homicides, shootings, robberies and carjackings in Chicago were all down since Border Patrol arrived.

We are here for YOU Chicago! Since we’ve BEAN here, crime is down:

⬇️Homicides down 16%

⬇️Shootings down 35%

⬇️Robberies down 41%

⬇️Carjackings down 48%

⬇️Transit Crime down 20%The United States Border Patrol is dedicated to making American cities safer, one deportation at a… pic.twitter.com/SVJnabMDUX

— Commander Op At Large CA Gregory K. Bovino (@CMDROpAtLargeCA) November 12, 2025

“It’s common sense,” Tricia McLaughlin wrote in a news release. “When you remove the worst of the worst criminal illegal aliens from our country, crime rates plummet.”

An analysis by WBEZ and the Sun-Times found the agency offered no data, no methodology and no timeframe for its claims.

Violent crime in Chicago was already falling before the operation began. The drop the Department of Homeland Security attributed to immigration raids matched or lagged behind declines seen in earlier months.

Experts and reporters were quick to point to the discrepancies and misleading crime statistics floated by Bovino and the federal government. But in other corners of the Internet, the post was celebrated by Trump supporters and out-of-towners as another major victory in immigration enforcement.

“When a narrative becomes what people buy into, even when it’s counterfactual, it justifies actions that would otherwise be unacceptable,” Nickell said. “And once that happens, the consequences can be really drastic.”

Listen to the Block Club Chicago podcast: