A shingles vaccination program that began in Wales in 2013 has led to two discoveries that give fresh hope to efforts to treat dementia: The vaccine appears to reduce the risk of mild cognitive impairment, as well as slowing progression of dementia in those already diagnosed.

We previously reported on the discovery that the vaccine may help prevent dementia in April, after results were published in Nature.

In a new follow-up study on the same data, this same vaccine has been linked to reduced cases of death by dementia in patients with an existing diagnosis.

The latest study, from an international team of scientists, adds to a growing body of evidence that stopping viruses that affect the nervous system – such as the varicella zoster virus, which causes shingles – could also protect against dementia.

Related: Time Itself Could Be a Crucial Element in Preventing Dementia, Study Finds

“Because the vaccine is safe, affordable, and already widely available, this finding could have major implications for public health,” says epidemiologist Haroon Ahmed, from Cardiff University in the UK.

“More research is needed to test our work and understand more about the potential protective effect the vaccine offers against dementia, particularly how and why it works.”

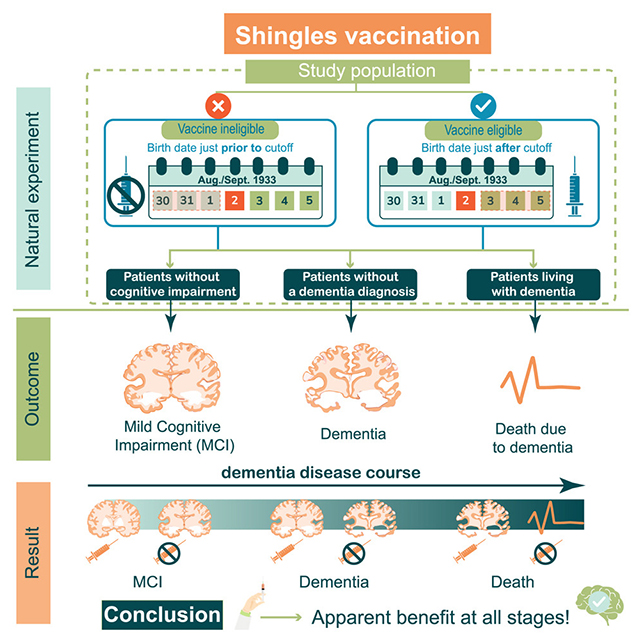

The vaccine protected against dementia and mild cognitive impairment. (Xie et al., Cell, 2025)

The vaccine protected against dementia and mild cognitive impairment. (Xie et al., Cell, 2025)

The Welsh vaccination program rolled out more than a decade ago by the UK National Health Service gave researchers the opportunity to analyze a randomized clinical trial, without actually running one: to ration vaccines, those aged 79 could get it, while those aged 80 couldn’t.

That quirk meant that the effects of the vaccine could be studied in two very similar groups, with an age difference of just one year between them. It goes a long way to reducing the influence of other factors that play into dementia risk, such as education level or other medical conditions.

Of the 14,350 people diagnosed with dementia prior to the start of the vaccine program, about half died of the condition within nine years. Being vaccinated against shingles made this nearly 30 percent less likely, according to the analysis, suggesting a significant level of protection.

The researchers also found that the vaccinated participants were less likely or slower to develop mild cognitive impairment, a common precursor to dementia. Combined with the earlier findings that the vaccine reduced the risk of dementia starting at all, these are encouraging signs.

“The most exciting part is that this really suggests the shingles vaccine doesn’t have only preventive, delaying benefits for dementia, but also therapeutic potential for those who already have dementia,” says biomedical scientist Pascal Geldsetzer from Stanford University in the US.

Even with the serendipitous design of the Welsh vaccination program, the data isn’t robust enough to show direct cause and effect – but it does show a significant connection that’s worth investigating further.

One of the next challenges is going to be figuring out why the shingles vaccine might be having this impact on dementia development and diagnosis. There might be nervous system or immune system mechanisms at play – viruses affecting the nervous system have been linked in animal models to the toxic protein build-up seen with Alzheimer’s, for example.

Further studies could potentially look at larger groups of people across a wider range of ages, as well as investigating the latest shingles vaccine: the vaccine used in Wales in 2013 has since been retired for a new and improved version.

“At least investing a subset of our resources into investigating these pathways could lead to breakthroughs in terms of treatment and prevention,” says Geldsetzer.

The research has been published in Cell.