In San Diego on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Amelia Machado Perez woke up in her house at 434 16th Street and readied herself for Sunday mass. She attended Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, less than a mile from her home. Amelia’s ancestral roots in San Diego were deep ones. Undoubtedly, she shared them with her children, especially when their teachers spoke about the history of San Diego. With pride, Amelia must have told her children that she was the great-granddaughter of Jose Manuel Machado, a prominent late 18th-century soldier and city leader in San Diego.

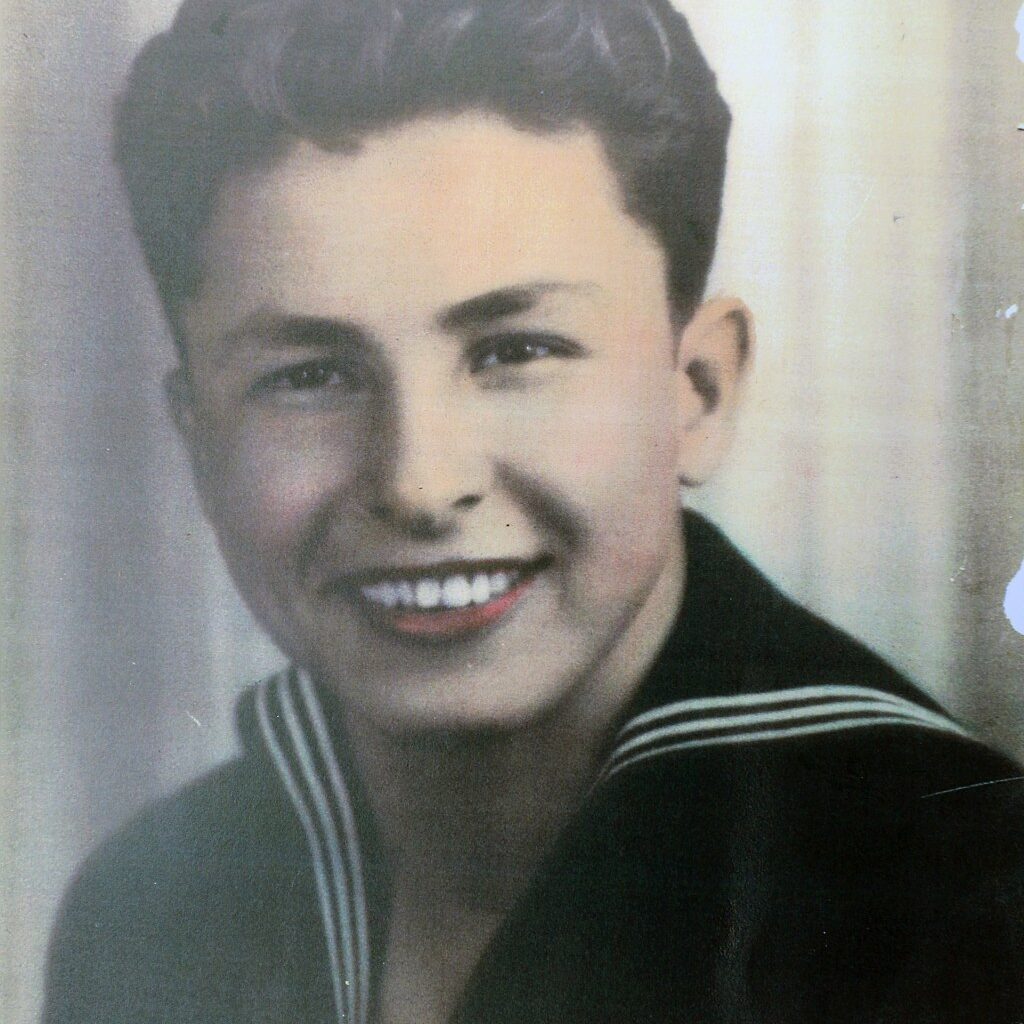

Amelia’s son, Rudolph “Rudy” Machado Martinez, followed his forefather’s example of military service. Born in San Diego on April 1, 1919, Rudy attended San Diego schools, including San Diego High School. He enlisted in the Navy in October 1939. Rudy joined the crew of the USS Utah that December. Although originally built in 1909 as a battleship, in 1932 it was recommissioned as a target ship. Military planes practiced bombing runs on her, using her deck as their target. On Dec. 7, 1941, the Utah was moored at Pearl Harbor. Her crew numbered 519.

The Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor began shortly before 8 a.m. on Dec. 7. Enemy planes dropped two aerial torpedoes and one bomb on the Utah. The ship’s port side took an underwater hit at 8:01 a.m., rupturing all of the port bulkheads. The Utah immediately began to list to port.

A second underwater hit quickly followed. It, too, struck on the port side. The third hit was a bomb. It apparently landed on the port side’s upper deck. An initial list — a nautical term for how much a ship is tilted — of about 15 degrees worsened. By about 8:05, the Utah was around 40 degrees to port, and at 8:12, some 80 degrees. Her mooring lines completely snapped. The Utah rolled over, capsizing around 8:13 a.m. The Navy eventually recovered the remains of only a few of the 58 who died, trapped in the Utah.

Amelia would have heard about the attack, probably in a radio broadcast, sometime after she arrived home from church. On Dec. 15, Secretary of the Navy William Knox announced the loss of six ships; he identified one as the Utah. Amelia still did not know Rudy’s fate, but she must have worried even more if she read the secretary’s statement in the newspaper the next day. Knox told reporters that the Navy suffered such high casualties “because some ships capsized.” On the 19th, Amelia received a telegram — “The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your son Rudolph Machado Martinez Electricians Mate Third Class was lost in action in the performance of his duty and in the service of his country.” The next morning, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church held a memorial service for Rudy.

The Navy never recovered the bodies of most who died on the Utah. Salvage operations concentrated on warships. The fact that over 50 men were entombed inside of the Utah did not make her a priority. What salvage crews did bring up was ordnance. On Dec. 13, divers entered the Utah. For days, they labored to remove powder, machine guns and ammunition from the magazines. The men wore respirator masks because they smelled hydrogen sulfide. In part, the gas was thought to be from the decomposition of the remains of those who died, trapped inside the ship. The deeper the divers went, the higher the concentration of hydrogen sulfide gas. Diving deeper was simply too dangerous. At the end of February 1942, the salvage operation was considered a success because of the thousands of ammunition rounds recovered. Salvage work on the Utah continued until March 1944, primarily to retrieve more equipment.

Today, the name “Rudolph M. Martinez” appears on a plaque on Ford Island’s Utah Memorial, not far from where the capsized USS Utah still rests. The other names are those of his fellow crewmembers who died with him on Dec. 7, 1941. Remember them all, especially on Pearl Harbor Day.

Dudik is president of the nonprofit World War II Experience. She lives in San Marcos.