A controversial New York City subway pilot program seeks to crack down on fare evasion by putting a delay on some subway emergency exits.

Rockefeller Christmas tree lights up in New York City

This year’s tree is 75-foot-tall Norway Spruce from just outside Albany, New York, with a 900 lb Swarovski star.

NEW YORK ‒ If you try to use the emergency exit at a New York City subway station, you may find it won’t let you out ‒ at least not right away.

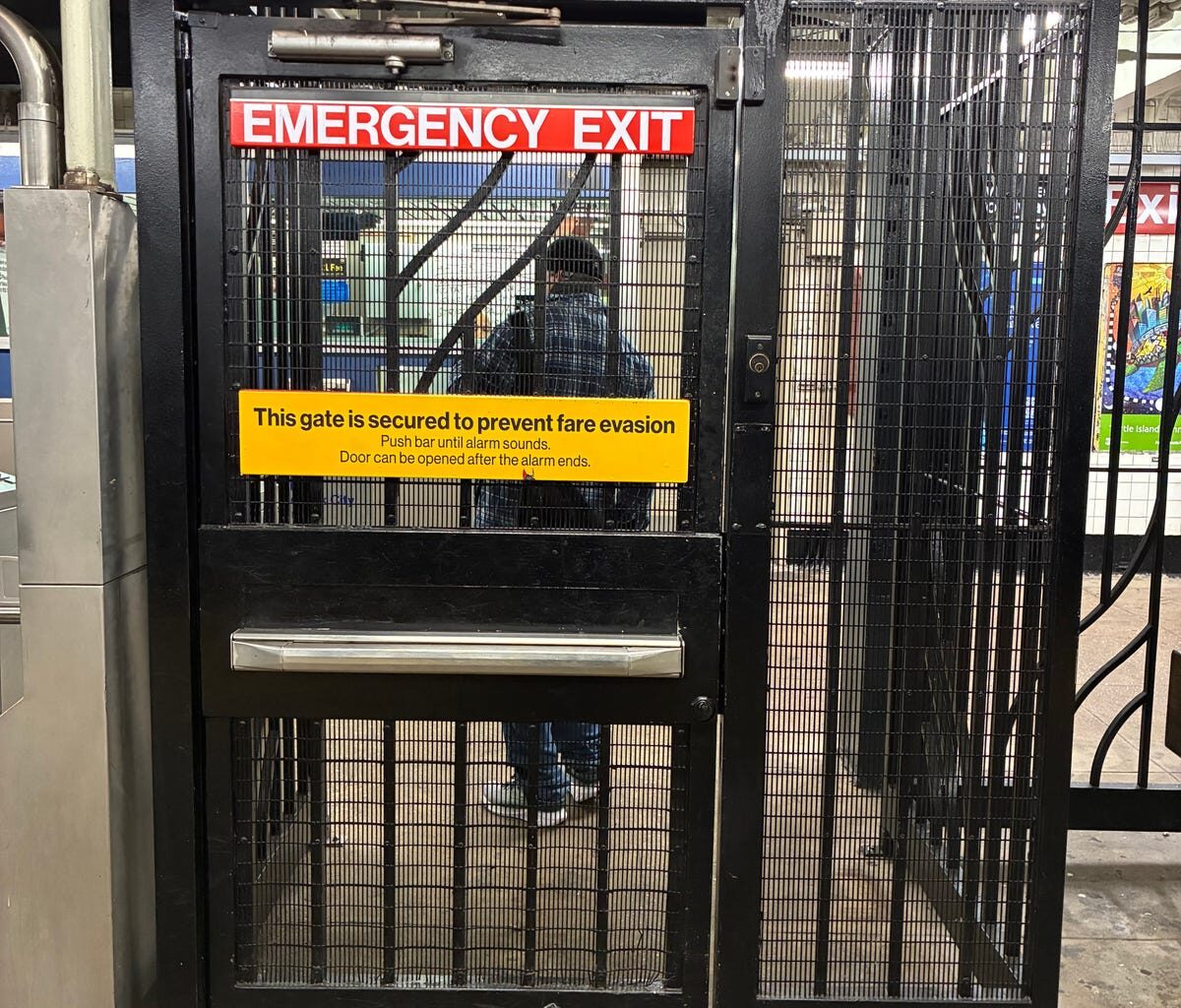

As a part of a sprawling effort to prevent riders from skipping out on fares, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has tried installing some new emergency exits that sound an alarm but don’t allow people to exit for up to 15 seconds.

In an emergency, officials said transit staff can release the gates, which have a yellow sign explaining they are designed to prevent fare evasion and will open after an alarm sounds.

But some riders have found the new doors troubling.

“It just doesn’t seem like a good solution just to prevent people going through the doors at the risk of actually putting, potentially, our lives at risk,” said Jack Klein, founder of the New York Lab, a coalition of researchers and community advocates who originally focused on extreme heat in the city’s subway.

On Thanksgiving, Klein filmed himself at a Lower Manhattan subway station waiting to open the emergency exit, garnering over 3 million views on TikTok.

New emergency exits are part of fare evasion crackdown

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, fare evasion has increased as ridership dipped, fueling a funding crisis for the nation’s largest transit system.

The MTA has taken measures to address fare evasion, including higher sleeves on turnstiles (to prevent jumping) and limiting turnstiles’ range of motion, according to the New York Times.

But emergency exits are a frequent route to evade the fare, according to an MTA report.

In response, officials have deployed private security guards across stations to stand at emergency exits.

And officials have spent around $11,000 per gate to install delayed emergency doors at 190 stations, for a total cost of about $2 million.

Laura Cala-Rauch, an MTA spokesperson, said the pilot program has been successful. Fare evasion is down 30%. On Dec. 5, Gov. Kathy Hochul announced ridership increasing after the onset of the pandemic.

Cala-Rauch said the program was evaluated as safe under state building and fire codes. In a statement, the New York State Department of State, which approved the new emergency exit system, said it reviewed MTA’s proposals and worked to ensure that the emergency egresses provided health, safety and security.

Eventually, the MTA has said it plans to move from outdated turnstiles to modern entrances that are harder to evade and more accessible, such as motorized swinging doors that open with a fare purchase.

Critics cite safety, accessibility worries

But people with disabilities have expressed concern. Already, the city’s subway has faced several lawsuits to comply with the federal Americans with Disabilities Act.

An emergency, like the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks nearly a quarter-century ago or the 2022 mass shooting aboard a Brooklyn train, can send people scrambling to leave stations. Deactivating the delay appears to be another thing that could go wrong.

“I don’t know if anybody is going to be holding the exit for everybody, because it’s every man and woman for themselves in the case of emergency,” said Sharon McLennon Wier, a psychologist who is executive director of the nonprofit Center for Independence of the Disabled, New York. “If that gate closes, and then you have to wait a few seconds, those few seconds could be death,” said Wier, who is also blind.

On a chilly Dec. 6, Betsy Shortt, a 39-year-old preschool teacher, and her daughter sat on a wooden bench on a northern Manhattan subway platform. The two, waiting for an A train, were about 15 feet from a set of delayed emergency exit doors. They planned to go ice skating.

“People will find ways to get through,” Shortt said. Subway fares, she said, add up, especially as fares will increase 10 cents in a month, from $2.90 to $3. The subway is a utility, as needed as the water or gas company, she said. “I can understand why people try to evade the fare.”

That afternoon, one of the newly installed delayed emergency exits wasn’t fully closed, so dozens of people − some towing strollers and bikes, others with just backpacks − walked through it to enter the subway.

Most headed downtown, all appeared to skip the fare.

Eduardo Cuevas is based in New York City. Reach him by email at emcuevas1@usatoday.com or on Signal at emcuevas.01.