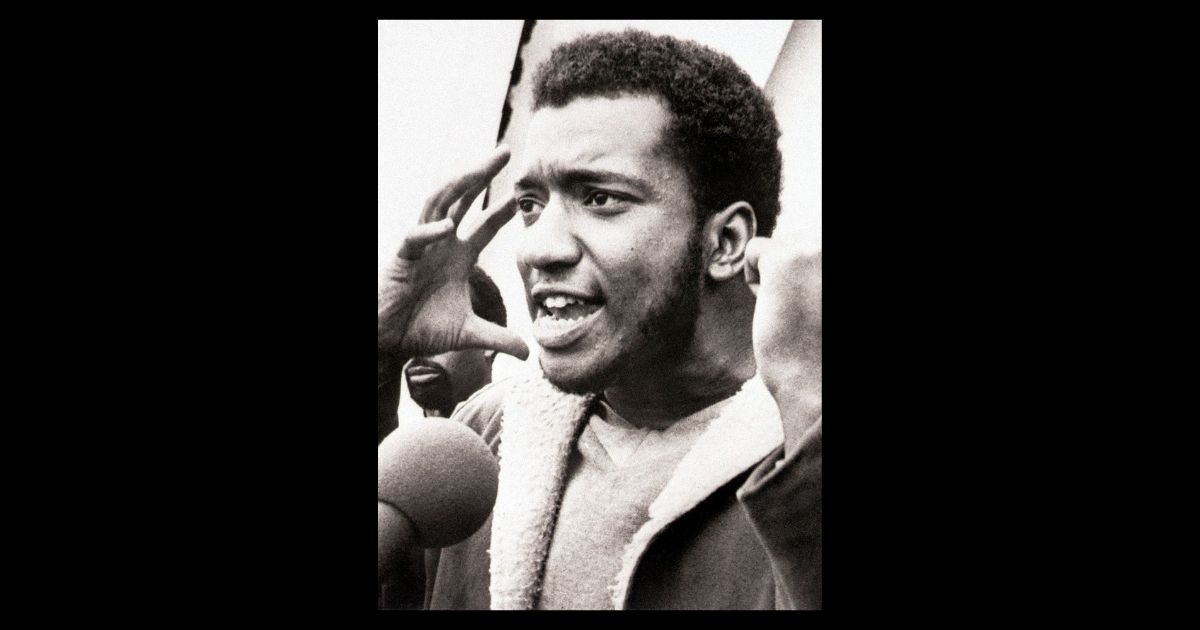

He was charismatic, brilliant, and unapologetically justice-seeking. Fred Hampton, Sr., was a 21-year-old expectant father when Chicago police officers killed him on December 4, 1969. His fiancée, Deborah Johnson, was nine months pregnant with their son. Fifty-six years later, as politicians move to slash school breakfast programs, gut Medicaid, and deport working families by the thousands, the voice of America’s “revolutionary” and coalition-builder echoes with unsettling clarity.

He was the chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, an organizer who fed hungry children while the government watched, and a strategist who united Black, Puerto Rican, Asian and poor white into a coalition so threatening that the FBI marked him for elimination. “You can kill a revolutionary,” Hampton told audiences across Chicago, “but you can’t kill a revolution.” On that December morning, the state tested his theory.

To understand why the federal, state, and local governments colluded to assassinate Hampton, one must first understand the Chicago he was trying to change.

Twenty months earlier, on April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in Memphis. Chicago’s West Side exploded. A 28-block stretch of West Madison Street burned. Over 200 buildings were destroyed. At least 11 people died. More than 2,150 were arrested. Property damage exceeded $10 million.

Mayor Richard J. Daley’s response was not restraint; it was an escalation. “I have given police the following instructions,” the mayor, once described as a modern-day pharaoh, told reporters. “Shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand… and shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting any stores in our city.”

Four months later, in August 1968, the Democratic National Convention descended on the city. Daley deployed 12,000 police on 12-hour shifts, 7,500 National Guardsmen, and 5,000 Army troops to confront anti-war protesters. Television cameras broadcast police beating demonstrators, pushing them through plate-glass windows, clubbing reporters and bystanders alike. Senator Abraham Ribicoff denounced “Gestapo tactics on the streets of Chicago” from the convention podium. A federal investigation later called it a “police riot.”

The mayor, however, rewarded the police with a pay raise.

This was the Chicago that Fred Hampton inherited. A city run by a Democratic Machine that operated, as Black activists and taxpayers charged, like a plantation. Racially segregated through redlined housing and gerrymandered school districts. Over-policed and underfunded. Black neighborhoods treated not as communities to serve, but as populations to contain. The numbers told the story of “Johannesburg on the Lake,” a phrase referencing South Africa’s apartheid system and often cited by Lu Palmer, a crusading journalist and activist.

In 1968, the national Black poverty rate stood at 34.7 percent, more than three times the white poverty rate. Black families were poor at a rate of 27 percent. More than half of all poor Black Americans were children under 18. In Chicago, concentrated poverty on the South and West Sides meant that entire generations grew up in neighborhoods where joblessness, hunger, and police violence were not aberrations but daily realities.

The federal government, consumed by war in Vietnam, had largely abandoned Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, a poor compromise to King’s prolific Poor People’s Campaign, derailed after his murder. The local government, under Daley, had never fought social inequality or for the city’s poor at all. Into this vacuum stepped the Black Panther Party.

THE MAKING OF A CHAIRMAN

Fredrick Allen Hampton Sr. was born August 30, 1948, in Summit, Illinois. His parents, Francis and Iberia, were migrants from Louisiana, part of the Great Migration that brought millions of Black Southerners north in search of freedom and opportunity. They settled in Maywood, a working-class Black suburb surrounded by affluent white communities. The proximity was instructive. Young Fred could see exactly how resources flowed and to whom they were denied.

He graduated with honors from Proviso East High School in 1966 and joined the NAACP Youth Council, building its membership to over 500. He organized marches for an integrated swimming pool, petitioned for better schools, and mobilized young people around tangible victories. He believed the system could be fixed. The rising youth leader even wanted to pursue a career in law.

Then came 1968.

King’s assassination, Daley’s “shoot to kill” orders, the convention riots, the poverty that persisted despite every civil rights law Congress had passed. Hampton drew a conclusion that would define his short life: the system was not broken. It was working exactly as designed.

In April 1968, Bobby Rush, then 21, had top secret military clearance and had recently received an honorable discharge from the U.S. military after going AWOL. He, along with Bob Brown, were young Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organizers, who eventually secured a Chicago charter from the Black Panther Party’s national headquarters in Oakland in the fall. Rush soon recruited Hampton, two years his junior, having seen him speak, garner press, and for his ability to move crowds with the persuasion and style of a Baptist preacher.

Rush, who would one day become a U.S. Congressman and pastor, was named Deputy Minister of Defense, handling security and logistics. Hampton became Deputy Chairman, the voice and strategist. Together, they built the most powerful Panther chapter outside California.

THE ASSASSINATION

At 4:30 a.m. on December 4, 1969, a 14-man police tactical unit organized by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office kicked down the door of Hampton’s apartment at 2337 West Monroe Street. They fired more than 90 rounds. The Panthers fired once. Mark Clark, 22, an activist from downstate Peoria on security detail in the front room, took a bullet to the heart. His shotgun discharged into the ceiling as he died. In the back bedroom, Hampton lay drugged by a Panther informant and motionless beside a visibly pregnant Johnson. Officers shot him twice in the shoulder. He was still breathing.

According to survivor testimony later confirmed in civil proceedings, an officer entered the room, observed that Hampton was still alive, and fired two shots point-blank into his head. “He’s good and dead now,” the officer reportedly said.

On Dec. 5th, another police raid was executed on Rush’s apartment, but the Panther leader had gone into hiding in a Catholic church and emerged two days later only after public assurances were secured that he would not be harmed. He surrendered to police on stage during Operation Breadbasket, in front of a throng of witnesses. The Deputy Minister of Defense had been at Hampton’s West Side apartment but received a phone call about a sick child and left just mere hours before the deadly raid, he recalled years later.

More than five thousand people filled the First Baptist Church of Melrose Park on December 9, 1969, to eulogize the slain martyr, according to Jet Magazine. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, Dr. King’s successor as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), delivered the eulogy. His words were unsparing. “The nation that conquered Nazi Germany,” Abernathy told the mourners, “is following the same course as brutal Nazi Germany.”

Rev. Jesse Jackson, then a young SCLC organizer, offered his own tribute: “When Fred was shot in Chicago, Black people in particular, and decent people in general, bled everywhere.” After the service, the family transported Hampton’s body to Louisiana. Fearing desecration in Chicago, they buried him in Bethel Cemetery in Haynesville, Claiborne Parish, in the ancestral soil his parents had fled.

Their fears proved justified. For decades, the headstone has been riddled with bullet holes, allegedly by white supremacists and off-duty law enforcement. No one has ever been charged. In 2019, the family installed a bulletproof barrier.

State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan immediately called the raid a “shootout” and claimed police had faced “vicious revolutionaries.” He staged a media reenactment and published photos of “bullet holes” in the apartment door. They were nail heads.

The Panthers countered by leaving the crime scene open. For weeks, thousands of Chicagoans walked through the bullet-riddled apartment, saw the blood-stained mattress, traced the trajectory of every round. All inward. Ninety shots fired by police. One discharged by a dying Panther into the ceiling. The police narrative collapsed in public. But the criminal justice system held firm.

In 1971, Special Prosecutor Barnabas Sears indicted Hanrahan and 13 officers for obstruction of justice. In 1972, a bench trial with no jury acquitted all defendants, offering no accountability or justice. The families of Hampton and Clark, represented by the People’s Law Office and attorney Flint Taylor, filed a $47.7 million civil rights lawsuit. For 13 years, they fought for access to FBI files, later documented as part of the vast counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO). What they eventually uncovered was the full machinery of the conspiracy.

William O’Neal, a teenage car thief facing felony charges, had been recruited by the FBI to infiltrate the Panthers. He rose to become chief of security and Hampton’s personal bodyguard. He provided the FBI with a detailed floor plan of Hampton’s apartment, marking the exact location of Hampton’s bed. He likely drugged Hampton’s Kool-Aid with secobarbital the night of the raid.

After the assassination, the FBI paid him a bonus.

In 1982, the case was settled. The City of Chicago, Cook County, and the federal government agreed to pay $1.85 million. It was the largest settlement in a police brutality case at the time. There was no admission of guilt. But a tripartite payment that was itself an admission: local, county, and federal agencies had conspired to assassinate a political leader on American soil. A year later, Chicago elected its first African American mayor, Cong. Harold Washington, a lawyer, firebrand, and former legislator who implemented King’s birthday as a holiday in Illinois.

WHAT HAMPTON BUILT

Depending on which version of history one agrees with, the U.S. government indirectly or explicitly participated in the assassinations of Min. El-Hajj Malik Shabazz (Malcolm X), King and Hampton because of what they were building: a multidimensional, multiracial, multinational coalition across class lines for human and civil rights—every component of which was in opposition to the most powerful nation on earth.

Malcolm built connections to African nations, King demanded reparations, social safety nets for the poor, an end to war and militarism and the full eradication of poverty. Hampton, through the Panther platform, stood against political repression, police violence, and economic injustice. J. Edgar Hoover, the infamous director of the FBI, authorized a full-scale attack on the rise of “Black militancy” and “radicalism” and deemed all as Black “messiahs” and national security threats.

The Black Panther Party for Self Defense, first organized in 1966, by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, emerged as the new face of Black resistance. While Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), co-founder of SNCC and a theoretical founder of the Party, called for Black Power, the Panthers, comprised of high school and college-age students and the “dispossessed” in urban America, embodied it.

Before donning the black leather jacket and beret, Hampton was a reformist. His work with the NAACP was characterized by pragmatic, tangible goals rather than abstract theorizing. He launched a campaign to secure a non-segregated swimming pool in Maywood, recognizing that Black youth had no recreational outlets, which contributed to tension and criminalization. He organized marches, petitioned school boards for better academic resources, and fought for integrated faculties.

However, the late 1960s presented a stark reality: despite the legislative victories of 1964 and 1965, the material conditions of Black people in Chicago were deteriorating. Police brutality was rampant, and the nonviolent, legalistic approach of the NAACP seemed increasingly inadequate to address the visceral violence of the state. Hampton began to view the problems of his community not as isolated incidents of prejudice, but as systemic features of capitalism and imperialism. This ideological evolution prepared him for the arrival of the Black Panther Party.

While the Free Breakfast for School Children program originated in Oakland in January 1969, Hampton’s Chicago chapter scaled and perfected it. By late 1969, the Panthers nationally were feeding 20,000 children a day. Chicago was a massive contributor, serving thousands weekly in neighborhoods the Daley machine had abandoned. Every bowl of grits came with a lesson.

Children were taught that they were hungry not because their parents were lazy, but because the system was designed to starve them. The Illinois chapter established the Spurgeon “Jake” Winters People’s Free Medical Care Center in North Lawndale. They launched mass screening events for sickle cell anemia, a disease the federal government had ignored.

The optics humiliated the government. In 1969, a federal administrator publicly admitted that the Black Panthers were feeding more poor children than the State of California. Chicago’s program effectively demonstrated its “tale of two cities” where both opulence and upward mobility lived in proximity to abject poverty, hopelessness, and a pre-designated permanent “underclass.”

Congress responded by dramatically expanding the School Breakfast Program, permanently authorizing it in 1975. In 1972, Nixon signed the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act. They utilized volunteer doctors and medical students, including allies such as Dr. Quentin Young, to test thousands of residents. The government did not adopt these programs out of benevolence. It adopted them to neutralize the Panthers by absorbing their programs and rendering the revolutionaries redundant.

But if the breakfast programs could be co-opted, the Rainbow Coalition could not.

Hampton understood the machine maintained its power by segregating the poor and exploiting class divides supported by a faulty “Talented Tenth” theory created by the Rockefeller Foundation and made popular by W.E.B. Dubois. He looked at the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican gang turned political organization and saw people suffering the same police brutality and substandard housing as Black residents. He looked at the Young Patriots, poor white Southerners in Uptown who wore Confederate flags on their jackets and saw the same class interests.

He convinced them their enemy was not the Black man on the West Side, but the banker and the capitalist. Hampton also began working with Black street organizations in an attempt to broker unity, though law enforcement, political leaders and others often attempted to pit the Chicago Panthers against the Black Stone Rangers, Disciples, and others. By many accounts, leaders such as Jeff Fort were starting to listen and thus also starting to be politicized. Thousands of youths across the city, county and state also began to organize and saw in Hampton a leader for their times.

Perhaps that is what killed him.

J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO directives had warned against the rise of a “messiah” who could unify Black nationalists and ultimately all African Americans into a united front. Hampton, an orator and strategic thinker, was doing something more dangerous. He was building a majority multi-racial, political coalition that could mathematically overturn the power structure of Chicago, and possibly the entire state. Could such a campaign ultimately lead to changes at the federal level?

Fifteen years later, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr., would seek to find out by launching his first run for the U.S. presidency under the banner of the National Rainbow Coalition. In 1983, Mel King, a state representative in Massachusetts, attempted to run for Mayor of Boston, calling his campaign the “Rainbow Coalition,” reviving Fred Hampton’s concept. He was the first Black person to reach a Boston general mayoral election.

According to an obituary in the Boston Globe, King said he “bequeathed the name to (Jackson).” An article from New Green Horizons reported, “The next stop was Boston, where Mel King hosted a campaign event. The Jackson campaign came out of Boston calling itself the Rainbow Coalition.”

WHAT WOULD HAMPTON DO?

Nearly six decades after Hampton’s assassination, the socio-economic contradictions within American democracy have only deepened.

The same federal government that was shamed into funding school breakfast programs now moves to slash them. The same apparatus that was forced to acknowledge sickle cell disease now threatens Medicaid cuts that would devastate Black communities with the nation’s highest rates of chronic illness. Voting rights, hard-won and blood bought, are being dismantled by courts and legislatures with surgical precision. After years of criminal justice reform, the prison-industrial complex appears to be on the rebound and rise.

And the playbook Hampton exposed is being deployed again.

Poor whites are told that immigrants and Black people are their enemies. Black communities are told to fear Latino migrants who are taking their jobs. Asians are pitted against other people of color, especially African Americans. The Courts are reversing hard-won civil rights gains. Meanwhile, the bankers, technocrats and the capitalists Hampton warned about continue to consolidate wealth and power, protected by a political class that offers representation without redistribution.

The data confirms the very future Hampton warned society against, a reality corroborated by the Economic Policy Institute and federal labor statistics. When the Chairman was assassinated in 1969, the federal minimum wage had the purchasing power of nearly $15 an hour in today’s money; today, the federal floor remains trapped at $7.25, forcing working families into a starvation cycle even as corporate profits soar.

In 1965, CEOs earned roughly 20 times the salary of their average worker; by 2024, that gap had widened to over 300-to-1, the Institute noted. Perhaps most damning is the rise of the prison state: The Bureau of Justice Statistics shows the U.S. incarcerated roughly 200,000 citizens when Hampton was alive. Today, that number approaches 2 million at an industrial-scale warehousing of human potential that disproportionately targets the very Black and Brown communities the Panthers sought to liberate.

What would Hampton do in 2025?

His son, Chairman Fred Hampton, Jr., who has not only kept his father’s legacy alive, but has emerged as a consistent voice for the oppressed knows: He would do what he did in 1969. He would walk into communities written off by both parties and speak directly to their material conditions. He would organize breakfast programs, medical clinics, and voter registration drives, fusing survival with political education. He would build coalitions across the very lines that power uses to divide us.

Hampton Jr., born 25 days after his father’s death, has continued his father’s work longer than his father was alive. He is the founder of the Prisoners of Conscience Committee and president and chairman of the Black Panther Party Cubs, which represents the children of party leaders and once included the late Tupac Shakur. In 2006, the Chicago City Council renamed the block of 2300 West Monroe Street “Chairman Fred Hampton Way.” In August 2025, some 19 years later, the city held a ceremony to finally unveil and install the street sign bearing his name.

In Maywood in 2007, the pool Hampton fought to integrate is now the Fred Hampton Family Aquatic Center. In April 2022, the west suburban city designated Hampton’s childhood home as a historic landmark. There are no public, K-12 charter or private schools named after him, as of this writing. Despite many universities citing Hampton in coursework or public programs, none have named a building, department or center after him.

A $26 million Hollywood film depicting the Black Panther leader was released shortly after the start of the global pandemic. At the 93rd Academy Awards, Daniel Kaluuya took home the Best Supporting Actor Oscar in 2021, and the film also won for Best Original Song with “Fight For You” by H.E.R., Tiara Thomas and D’Mile. “Judas and the Black Messiah,” primarily focused on the paid FBI informant who helped facilitate his murder.

Yet Hampton’s legacy lives on.

“My father was physically taken from me—I never met him,” Hampton, Jr., once told this writer. “But my mother, Akua Njeri, and the people who knew and loved him, made sure that I not only carried his name, but his spirit of leadership and commitment to the people as well. If he were here, he’d be fighting the conditions in these prisons, standing up for poor people, challenging the politicians—no matter who they were or what skin color they were, and making sure that our human rights were respected.

“He would call out the contradiction,” he told the Crusader. “He would point out a government that claims it cannot afford to feed children while funding tax cuts for the wealthy, where they pay farmers not to grow food. He’d be against corporations profiting from the people’s labor and not paying a living wage. He would speak against a political system that celebrates Black faces in high places while Black neighborhoods crumble from disinvestment.”

And, in the wake of President Trump’s commitment to infusing U.S. cities with the National Guard, immigration enforcement agents and a masked police force? Based on his legacy, Chairman Fred Hampton, who would have turned 77 this year, would remind us that the enemy is not the family seeking asylum at the border, the poor worker losing his job to automation or Black mothers working three jobs to keep her children fed.

He would tell us it is the system that keeps all of them fighting each other while the powerful divide the spoils. Every child who eats a free breakfast in public schools is proof that Chairman Fred Hampton was right. Any person who has access to critical treatments and healthcare at federally funded community clinics and hospitals proves that he was right.

And any politician moving to cut those programs proves exactly why they killed him..

Stephanie Gadlin is an award-winning, independent investigative journalist whose work blends historical analysis, data reporting, and cultural commentary. Her work is published in the Crusader and other publications across the country. She specializes in uncovering the intersections of Black culture, public health, environmental justice, systemic racism, public policy and economic inequality in the U.S. and across the African Diaspora. For confidential tips, please contact: [email protected]