The word “uncertain” is often found in economic forecasts that try to predict the future. For the 2026 Colorado Business Economic Outlook, to be released Monday, there could be a record amount. The term, or a version of it, appears 72 times, or closer to three times more frequently than last year — and 20% more than in the report written during the worst of the pandemic five years ago.

In a year filled with on-again and off-again tariffs, government hiring freezes and layoffs, zeroed-out federal grants, immigration policy changes, plus the longest federal government shutdown in U.S. history, putting together this year’s book had its own set of unique challenges.

“There were things that were changing on a weekly, if not daily basis, that made the report more challenging to write,” said Glenda Mostek, executive director of the Colorado Nursery and Greenhouse Association, who also chaired the agriculture section of this year’s report. “We met in mid-October and the report had to be written by Nov. 1. And so right after our meeting, (U.S. Farm Service Agency) offices opened back up for farmers to get disaster aid. And the government reopened.”

The Colorado Business Economic Outlook for 2026 will be available publicly on Dec. 8, 2025. The annual report is overseen by the University of Colorado Boulder’s Leeds School of Business and involves more than 130 experts in various industries.

The Colorado Business Economic Outlook for 2026 will be available publicly on Dec. 8, 2025. The annual report is overseen by the University of Colorado Boulder’s Leeds School of Business and involves more than 130 experts in various industries.

She tried to write her part of the report to consider various scenarios so it wouldn’t seem out of date by December. And even though the Trump administration removed some tariffs on beef imports after the committee wrapped up, the ongoing chaos of trade policies were already accounted for. Hence, farm income in Colorado is expected to fall 18% to $1.8 billion in 2026, down from $2.2 billion this year, according to the report.

“The effect will show up next year because a lot of farmers and in my industry, nursery and greenhouses, bought supplies that they expected would be covered by tariffs. A lot of buying was done in the first quarter this year,” Mostek explained. “I know some farm and ag accountants were raising their eyebrows at expenses happening back then, but they avoided tariffs that were implemented later in the year.”

Brian Lewandowski, executive director of the Business Research Division at University of Colorado Boulder, Leeds School. (Tamara Chuang, The Colorado Sun)

Brian Lewandowski, executive director of the Business Research Division at University of Colorado Boulder, Leeds School. (Tamara Chuang, The Colorado Sun)

And that just means 2026 projections are, well, uncertain. That’s kind of the theme of this year’s report, coming together as it always does with guidance from about 130 people representing various industries, businesses and government agencies in Colorado. It’s produced by the Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado.

“One overarching theme this year is we’re expecting much slower growth than what we’ve experienced for the last several years,” said Brian Lewandowski, executive director CU’s Business Research Division. “And even when we look at our overall forecast, the 2026 forecast within the margin of error could even be a little bit negative to more positive.”

Job growth so slow, you’d think there was a recession

His colleague, senior economist Rich Wobbekind, chimed in about how that could be: Different data contributes to the overall forecast figure.

Richard Wobbekind, Associate Dean for Business & Government Relations, Senior Economist and Faculty Director of the Business Research Division and at the University of Colorado Boulder. (Tamara Chuang, The Colorado Sun)

Richard Wobbekind, Associate Dean for Business & Government Relations, Senior Economist and Faculty Director of the Business Research Division and at the University of Colorado Boulder. (Tamara Chuang, The Colorado Sun)

For the state’s GDP, this year’s estimate is that Colorado is up 2.1% and next year, the forecast is an annual gain of 2.9%. But job growth? That is so low, it’s better to say it’s flat.

When all is said and done, Leeds economists estimate Colorado will add 12,500 new jobs this year, and 17,500 new jobs next year. Those are just fractions of the state’s roughly 3.16 million jobs, so this year’s job growth rate is 0.4% and next year’s is 0.6%.

Here’s how job growth or declines for the different sectors are expected to end up this year and next year, according to the Leeds’ report:

“There’s two things to keep in mind here,” Wobbekind said. “One is growth in employment, and one is growth in output. I’d be really surprised if there’s not positive GDP growth for the year. (But) with the pullback in immigration, the visas and so on, it’s going to be very slow growth in our total labor force for Colorado. Year over year right now is basically flat. … You could see a situation where you’ve got growth in output but you don’t have much growth in employment.”

But they’re not predicting a recession because of the GDP growth.

“These are really the two slowest growth years since the pandemic recession,” Lewandowski said. “And if you look back over 20 to 25 years, it’s really unusual to have this slow of growth without entering a recession or without just exiting one.”

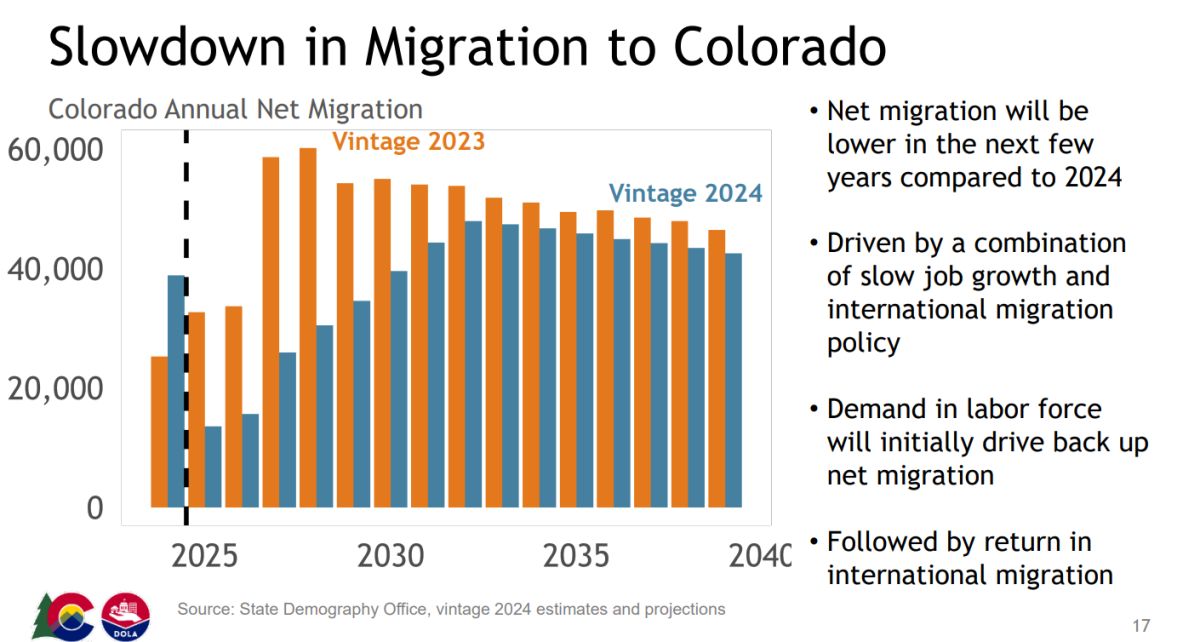

Some of the projections are based on new estimates from the State Demography Office, which revised the state’s population forecast downward last month due to lower international immigration.

“That’s a very different thing,” Wobbekind said. “We’re not used to Colorado’s population not growing. And we’re not used to people from other parts of the country not coming to Colorado. And I’m not talking about internationally but within the country.”

In the latest population update from the State Demography Office on Nov. 7, 2025, State Forecast Demographer Neal Marquez shared a slide showing how the year’s slowdown in job growth plus changes to international migration policy is slowing the number of new residents migrating to Colorado. The “Vintage 2024” is the revision to prior estimates. (Screenshot)

In the latest population update from the State Demography Office on Nov. 7, 2025, State Forecast Demographer Neal Marquez shared a slide showing how the year’s slowdown in job growth plus changes to international migration policy is slowing the number of new residents migrating to Colorado. The “Vintage 2024” is the revision to prior estimates. (Screenshot)

Other economists feel less conservative about the state’s job prospects. Thomas Young, senior economist with Common Sense Institute in Greenwood Village, felt the report’s job growth estimate for this year was too low.

Based on nonfarm job growth through August this year, Young said Colorado was at 2.992 million jobs or up 14,000 jobs for the year thus far. That’s a 0.6% growth rate. If it drops to 0.4%, that means Colorado lost 2,000 jobs between August and December.

“Instead of losing jobs for the remainder of the year, I think we’ll keep adding, albeit by historical standards, slow. I think something like +18,000 job growth for the year, so adding another 4,000 between now and the end of the year instead of losing 2,000,” Young said in an email.

Gary Horvath, an economist in Broomfield, is even more optimistic. “I expect Colorado employment will increase by 25,000 this year and 35,000 in 2026,” he said in an email. “The U.S. economy was driven by uncertainty in 2025. The economy will be more settled in 2026. Colorado will benefit from reduced uncertainty.”

Manufacturing expected to grow again

For the third year, Colorado manufacturers lost workers again, declining 0.9% this year. Blame artificial intelligence and automation — or credit the technologies for improving next year’s prospects. Manufacturing jobs are expected to grow by 1% to roughly 149,200 jobs in 2026.

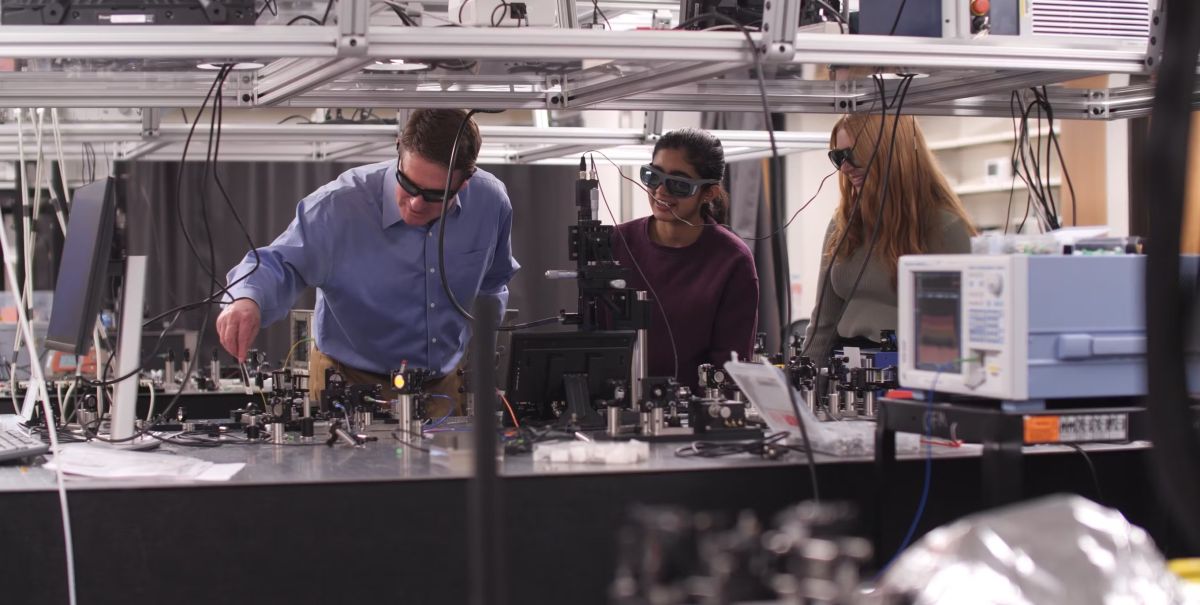

While concerns about federal immigration policies and local workers was a topic of discussion for the report’s working group, members felt the impact was minimal, at least in Colorado, where the largest nondurable goods manufacturing is food. That sector is expected to add 1,100 jobs next year, a 1.9% annual growth rate. There’s also a growing number of manufacturing jobs that require training and skills, like aerospace, quantum computing and clean tech.

University of Colorado Boulder with partners Elevate Quantum and other universities announced it would open a quantum incubator in Boulder for startups and researchers interested in taking ideas out of the lab and turning them into reality. (University of Colorado, Boulder)

University of Colorado Boulder with partners Elevate Quantum and other universities announced it would open a quantum incubator in Boulder for startups and researchers interested in taking ideas out of the lab and turning them into reality. (University of Colorado, Boulder)

“There has been a lot of automation happening in the sector anyway,” said Jennifer Hagan-Dier, vice president of Manufacturer’s Edge in Lakewood, who sat on the committee. “We’ve seen a dramatic change in the adoption of robotics and digital manufacturing because it’s become cheaper and easier to access.”

But there’s still plenty of other challenges, including getting the state’s smaller makers up to speed on how to implement and use technology. Manufacturer’s Edge, an official Manufacturing Extension Partnership that’s partly funded by the federal government, is tasked with supporting those small-to-midsized manufacturers by providing support, training and technical assistance.

“(AI) can be used for demand planning, or maybe you don’t have a person on staff but you need to figure out what your inventory needs to look like over the next 12 months. If you have the right prompts, and the right AI tool, it can do that work for you,” Hagan-Dier said. “That’s the artificial intelligence side. On the other, there’s prototyping and all kinds of other things. From our perspective, we have to start the educational component.”

The organization hopes to offer a series of AI workshops. But speaking of uncertainty, Manufacturer’s Edge found out federal funding for MEPs across the country was “zeroed out” and some lost funding and had to shut down.

The Lakewood organization has revenue since it must match every federal dollar, but had to lay off half its staff, which now numbers seven. After MEPs reached out to lawmakers, the Trump administration reversed the decision, at least for 10 states, including Colorado. However, it’s just for one year instead of the old 10-year agreement.

“It’s been fight or flight since January,” Hagan-Dier said. “I’m built for chaos, but at this point, I could use one week where things just don’t go like this.”

Type of Story: News

Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.