This essay was adapted from one that first appeared at The Bigger Apple, the Manhattan Institute’s newsletter dedicated to everything you need to know about New York City. Subscribe today!

New York provides many social services via private nonprofits (NGOs) instead of delivering them directly via the city’s municipal workforce. In all the chatter about the 2025 mayoral election, some commentators speculated that the NGO workforce contributed heavy support to Zohran Mamdani’s campaign. This claim, plausible if hard to prove, points toward a political model distinct from the “new Tammany Hall” government union model familiar to observers of early twenty-first century city politics.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The NGO workforce is broadly nonunion and paid less, especially with respect to benefits, than the unionized municipal workforce. Administratively, NGOs deliver bang for the buck. When the government wants to scale up a service, such as community-based mental health programs, homeless shelters, or alternatives to incarceration, NGOs allow it to do so widely and rapidly.

Politically, using NGOs, as opposed to better-paid municipal workers, is a model better primed to fuel the kind of economic resentment said to energize the Mamdanians, while expanding their ranks. It’s ingenious when you think about it.

Accounting for Mamdani requires explaining the scale of his support (the tens of thousands of door-knockers) and why it became possible now.

Socialists have been lurking in New York for years, but they didn’t break through until the 2020s. Mamdani received minimal support from organized labor in the Democratic primary, and unions are not stronger now than they were in the 2000s. So, the “new Tammany Hall,” which reduces city politics to an exchange of votes for generous contracts to teachers and other unionized workforces, is only so useful.

The NGO model explains more:

- During this century, New York City has seen “full-time core human services employment” grow by close to 150 percent.

- The New School’s Center for New York City Affairs estimates that city government indirectly supports over 80,000 private nonprofit social services jobs and that

- When benefits are included, those jobs pay almost one-third less than comparable public-sector jobs.

- State comptroller Thomas DiNapoli estimates that the public vs. nonprofit pay gap in “Health Care & Social Assistance” jobs is over $20,000 a year.

- A 2023 analysis found that, between 2000 and 2020, New York State’s private mental health workforce grew by over 100,000, whereas state government’s mental health workforce declined by about 4,000; and that wage growth was more robust for public-sector workers.

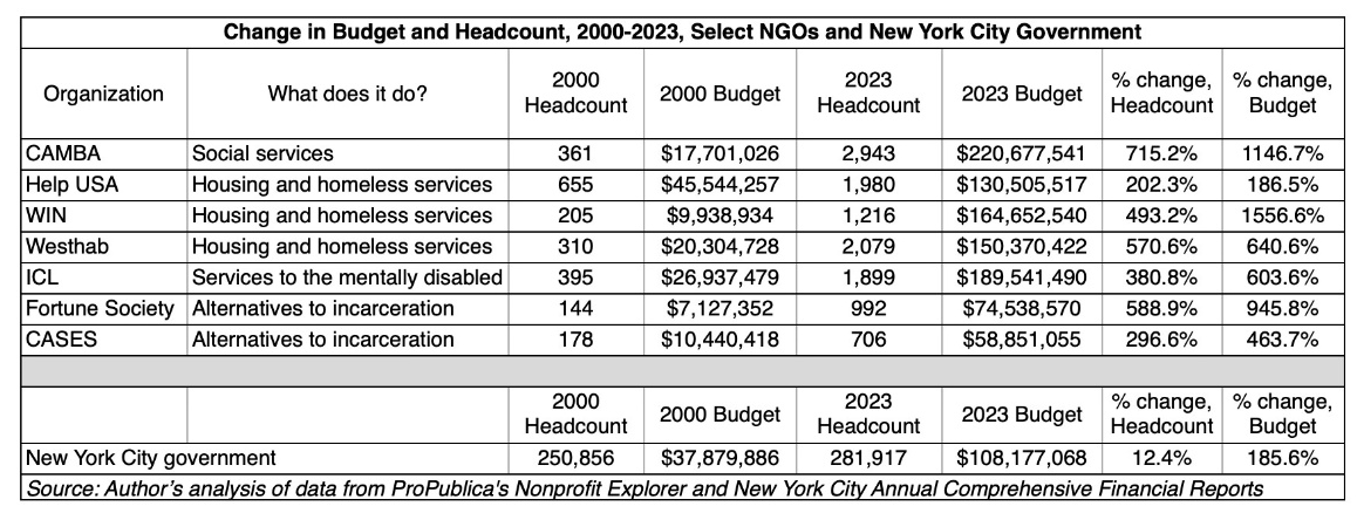

The table below shows some examples of NGOs whose growth rates—budget and workforce—have radically outpaced those of the municipal workforce and overall city budget.

In sum, there are now heaps more lower-paid NGO workers around than there were 20 to 30 years ago.

That NGOs shape city politics is not exactly a secret. But progressives and conservatives have both been slow to grasp the full implications of NGOs’ heft in 2020s New York.

Progressives have always been ambivalent about NGOs, because any form of delivering a public service through private means carries overtones of “privatization” or “neoliberalism” (charter schools are NGOs, for example). Progressives have thus to some degree overlooked what a gift they’ve been given.

Conservatives tend to conflate the “social services industrial complex” NGO and “new Tammany Hall” government-union models. They’re different, and the shift toward increased reliance on the private nonprofit sector in fact represents a certain conservative victory. During the Tea Party era of the early 2010s, conservatives labored to expose the corruption and inefficiency associated with the union-centered new Tammany Hall model. These analyses focused closely on city workers’ generous pension benefits.

I participated in that conversation. I vividly remember at certain points someone raising the question: Would it really be better if city Democrats redirected the money blown on teacher pensions to social service programs of questionable effectiveness? In any case, that’s what happened.

It turns out that somewhere deep within the recesses of blue-state city governments, budget officials were heeding conservatives’ pension critiques. Pensions are New York City’s third-highest expense after education and social services; nonwage benefits make up 42 percent of the $56 billion “personal service” budget. To control costs, the city expanded contracting out.

More people benefit from alternatives to incarceration when that’s contracted out. Perhaps not coincidentally, there are more Mamdani voters around when alternatives to incarceration are contracted out.

Another conservative blind spot has to do with philanthropy.

Many big-time New York NGOs fundraise from private donors to supplement their government contracts. Conservative Substacker Arnold Kling is a longstanding critic of the belief that, all things being equal, nonprofit work is more honest than for-profit work. He has further argued that philanthropy’s activities help spread that belief.

Critics of the “social services industrial complex” also misunderstand the NGO model’s compensation dynamics when they focus too much on executive compensation. Yes, some NGO chiefs are paid handsomely, earning more than they would leading a major city agency, and they often enjoy long tenures. That’s important, because term-limited city councilmembers covet those jobs—and may, therefore, while in office and possessing oversight authority, refrain from using that authority to expose corruption and ineffectiveness in a social services sector in which they hope to land a job soon. But politically, the fact that NGOs use lots of low-paid employees is more important than the fact that they employ a handful of very well-paid ones.

The United Federation of Teachers remains a political powerhouse in New York City. The NGO model will not displace the new Tammany Hall. In fact, its expansion depends on fiscal anxiety associated with the pension-freighted government-union model. But NGOs do qualify unions’ influence. The model also points toward a less directly transactional, perhaps more ideological style of city politics. Elected officials energize municipal unions by boosting their pay. They energize true believer NGO employees with partisan rhetoric.

Another implication: hiring more cops would be politically suicidal for Mayor Mamdani. Public safety unions have long existed as an interesting fly in the ointment of the new Tammany Hall model. Democrats, completely untroubled by teacher union corruption, inveigh at police union leaders as reactionary figures in public life. Substantively, though, it’s hard for Democrats to do much about police unions without being seen as anti-worker and embracing the highly toxic “defund” brand.

So, they deploy patronage: reduce the NYPD through attrition and maximize investment in social services. That way, assuming a multiplier effect, for every three or four law-and-order votes (police officer and other adult members of his household) that are lost, something like five or six NGO votes (social worker and her family members or roommates) will be gained.

Many centrist Democratic mayors are wondering: Is Mamdani a bellwether? Can it happen in my city?

One factor to weigh is the size of a city’s NGO sector. Local government functions as the employer of last resort everywhere, even in red America. But New York is unique in the extent of city and philanthropic resources committed beyond what the federal safety net provides and the magnitude of its private nonprofit sector.

A large NGO workforce doesn’t automatically turn a city socialist. San Francisco’s formidable nonprofit sector didn’t prevent its current moderate leadership from emerging. But it does ensure that political truths that held in the early 2000s apply with less force in the 2020s.

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal.

Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images