Dr. Andrew Lipton’s parents maintained a modest lifestyle in Penn Valley. The revenue from the small chain of gift shops they ran put their son through medical school, and he became an osteopathic family doctor with a decades-long practice. At Narberth Family Medicine and Acupuncture Center, Lipton’s business model continues to serve him well in an ever-changing healthcare industry.

Increasingly, though, Lipton is the exception. In short, many primary care physicians have had it. They get all the work but little to none of the financial rewards. Many practitioners in general, family or internal medicine are repurposing or retiring early. The third option is accepting a buyout from one of the health networks swallowing up the dwindling number of independents beset with the escalating costs and burdens of running a private practice. “It’s overwhelmingly expensive,” says Lipton. “An EKG machine alone costs thousands—or you can join Main Line Health … where you don’t need to also be an entrepreneur.”

In the early 1980s, three-quarters of doctors in the United States owned their own practices. Today, fewer than half do. The push to moderate costs has led hospitals to start buying up practices, initiating managed care of the patient’s comprehensive needs across an entire health system. It makes sense, then, to integrate physicians into those networks. But the trend has also led to a less personal approach.

Lipton has teamed with his wife, acupuncturist Mary Ann Settembrino. Together, they make a reasonable living. In more than a decade in primary care, he’s had just one resident who wanted to go into private practice. “But she also had a husband/partner with finances,” he notes.

These days, it’s rare for a medical student to consider a career as a primary care physician. The shortage on both ends is snuffing out what was once the cornerstone of medical treatment—the patient-doctor relationship. There was a time when family physicians were integral and revered community members. They might’ve seen 50 patients a day. Some of us may be old enough to even remember house calls.

Since then, the number of Americans with a personal physician (traditionally the first point of contact in the healthcare system) has been steadily declining, particularly for younger patients. As of 2018, nearly half of adults under 30 didn’t have a primary care doctor—and that was seven years ago, pre-Covid. Even PCP terminology is troublesome, as “primary” has two conflicting definitions. It can mean either “the foundation of the rest of it or the first level and not so important,” says Dr. Christine Laine, who lives in Wynnewood and teaches in the internal medicine departments at both Jefferson and Sidney Kimmel medical colleges in Philadelphia.

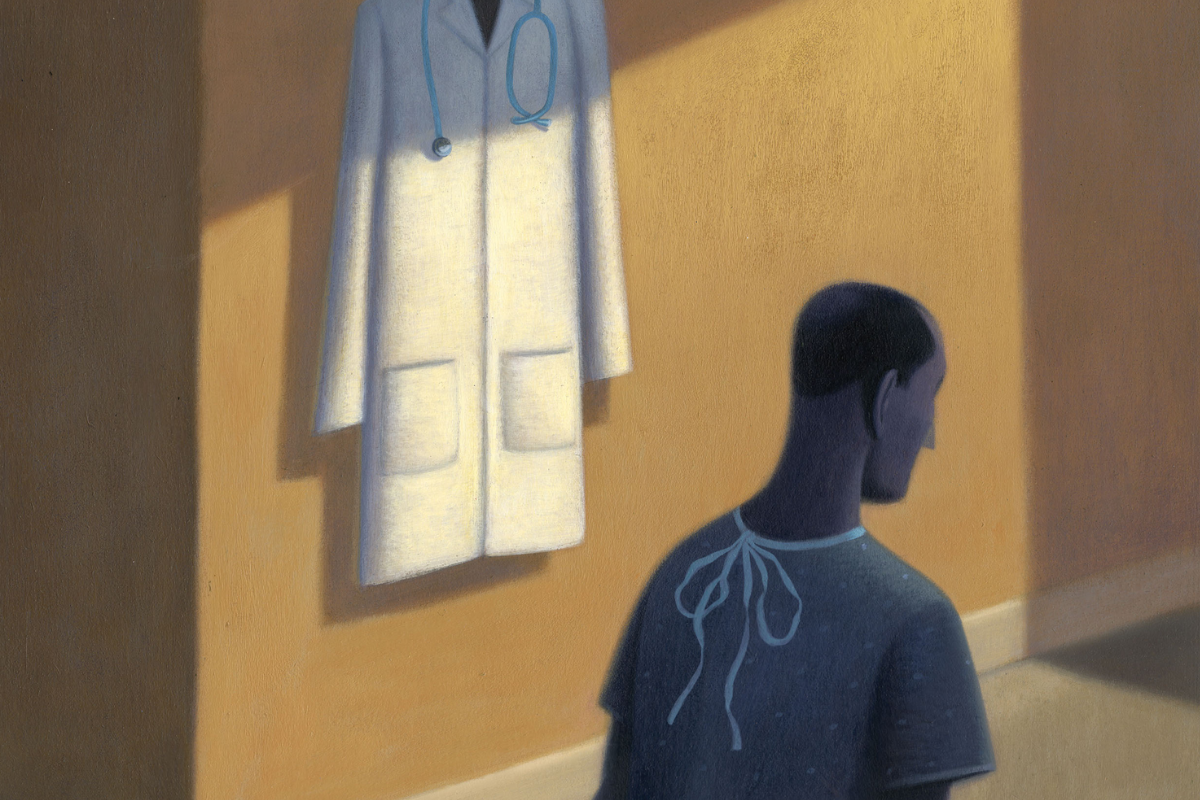

Illustration by Jon Krause

Illustration by Jon Krause

“THERE’S SIMPLY MORE MONEY AND STATUS TO BE HAD AS A SPECIALIST IN CARDIOLOGY, ONCOLOGY, PULMONOLOGY AND OTHER FIELDS.

Laine does her part to try to convince residents of the rewards of becoming a generalist. Meanwhile, younger patients are opting for the convenience of urgent care and retail-style clinics, emergency rooms, and even AI-powered self-diagnosis. It’s all “patchwork” to Laine, who’s also editor-in-chief of the “Annals of Internal Medicine,” a publication of the Philadelphia-based American College of Physicians, one of the professional organizations charged with changing current perceptions. “But it’s hard to convince 20-somethings,” she says.

Increasingly, the nurse practitioner has become the physician’s proxy. But it’s “shortsighted to think you can replace PCPs with them,” says Laine.

Laine sees the potential restoration of the field as complex and multilayered. At the forefront: more equitable compensation between PCPs and specialists. “It’s no big mystery why medical school students aren’t going into primary care,” she says.

There’s simply more money and status to be had as a specialist in cardiology, pulmonology, nephrology, oncology and other fields. Either that, or you allow yourself to get gobbled up by health systems and corporate entities.

According to a recent report from the nonprofit healthcare research foundation Milbank Memorial Fund, one in three U.S. doctors still practices primary care—but among young physicians two years into their careers, the share is one in five. The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortage of as many as 48,000 primary care doctors by 2034.

“The top question I get is, ‘Can you find me a PCP?’” says Laine, who had to tap the “favor bank” to get one for herself. “The ones in practice are busy and full. It should actually strike fear in your heart to learn that your physician is retiring.”

Dr. Peter Edde was the first in his family to attend college, let alone medical school. “Growing up, I knew doctors came and healed you,” says Edde, who was born and raised in Lebanon and currently practices internal medicine at Penn Medicine Radnor. “I wanted to do that, pursued it and have enjoyed the path—a straight family-medicine track.”

After earning his degree from the American University of Beirut Faculty of Medicine and completing a one-year residency at home, Edde came to Norristown for a full residency at Montgomery Family Practice. He’s a 20-year veteran of a service model he knows is in flux. “The encounter has become different, and so has the patient experience,” he says. “Now, you’re not talking to patients so much as talking to the computer. You’re gathering information from the exam, but you’re also drawn to the computer. There can be minimal eye contact, and a relationship can get lost. It’s become more mechanical and less clinical.”

Something else may be lost under the new model. One recent study found that when patients begin to distrust or drop their longtime primary care doctor, their emergency room visits and hospital admissions increase along with their mortality rate. At Edde’s Penn Medicine practice, physicians have a half hour to see each patient. “The job’s harder depending where you’re practicing and how well organized that system is,” he says. “Demands, expectations and administrative burdens can be more, but if you’re surrounded with the right team, it can make it better.”

Among the 16 practitioners at his office, Edde is one of 10 in primary care. His group is divided into small teams of two to four physicians and one or two nurse practitioners. “We don’t just want to see patients and get paid—we want to see them and manage their care to keep them as healthy as possible,” Edde says. “When we manage healthcare as much as possible, the patient, the healthcare industry and the insurance companies all win.”

And the only way to survive may be to join a large institution, as Edde has done. It means a guaranteed salary, paid vacation and other perks. “I’ve met others in private practice who say they haven’t gone on vacation in 14 years,” Edde says. “To survive, they need to do extra things.”

That’s exactly where Lipton’s found himself. “Starting from day one, I didn’t want to be anyone’s employee,” he says. “When you come from an entrepreneurial background, you don’t want to be employed. It’s harder to be stubborn, so it’s not for everyone.”

A half dozen associate medical practitioners have come and gone after short stays at Narberth Family Medicine and Acupuncture Center. “The extra work falls on the primary care physician, never on somebody else,” Lipton says. “It’s the time and money spent.”

Courtesy of Lauryn Swavely

Courtesy of Lauryn Swavely

“THE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN MEDICAL COLLEGES PROJECTS A SHORTAGE OF AS MANY AS 48,000 PRIMARY CARE DOCTORS BY 2034. “THE ONES IN PRACTICE ARE BUSY AND FULL,” SAYS DR. CHRISTINE LAINE. “IT SHOULD ACTUALLY STRIKE FEAR IN YOUR HEART TO LEARN THAT YOUR PHYSICIAN IS RETIRING.”

Recently, Lipton’s expenses have skyrocketed. Before the pandemic, he could hire a medical assistant for $12-$15 an hour. Today’s rate is $19-$20. And rent keeps going up. “The writing is on the wall,” he says. “I’m 62. I love what I do. But how can I run a business if costs keep going up and [patient, Medicare and insurance] payments keep going down?”

As a way to stay in business while gradually moving toward retirement, Lipton is actively researching how to convert his practice into a more financially feasible membership or concierge model. For the patient, this involves an upfront fee—a retainer of sorts that provides a steady source of pre-paid income. It’s a national trend that’s growing in popularity, with an estimated 1,300 U.S. practices. But it only serves a small, more affluent percentage of the population, maybe 400,000 patients.

Courtesy of Narberth Family Medicine and Acupuncture Center

Courtesy of Narberth Family Medicine and Acupuncture Center

DR. ANDREW LIPTON IS ACTIVELY RESEARCHING HOW TO CONVERT HIS PRACTICE INTO A MORE FINANCIALLY FEASIBLE MEMBERSHIP OR CONCIERGE MODEL.

Any change of that nature, however, would bump Lipton out of the system. “It might eliminate 60 to 70% of my patients,” he says. “Some call it elitist because only the wealthy can see you. I have patients in their 80s on Medicare, and I’ll feel guilty if this drops them or they drop me.”

But Lipton also sees the benefits. “I’m asking my patients to buy into what I do like a lawyer is retained to figure out your case,” he says. “You don’t have to join, so it excludes me from legal repercussions.”

Ideally, Lipton hopes it would be enticing for enough patients. “I want to present an offer you can’t refuse and hear, ‘I like you. I like what you do, so why wouldn’t I join?’” he says.

It’s also a solution that could help stave off active venture capitalists who often encroach with offers to buy the practice. “If I don’t make some sort of move, I’ll either fail or retire,” says Lipton.

Related: Menopause on the Main Line: Local Experts Offer Support