The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia gets a lot of different reactions from a lot of different people.

For some, it’s awe at all the different ways the human body can develop, from the death plaster of conjoined twins to the “Soap Lady.”

For others, it’s a way to marvel at just how far science has come: The museum’s founder and namesake, Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter, lived in a time when medical practices now seen as standard — like the use of morphine — were viewed, quite frankly, as cuckoo, according to “Dr. Mutter’s Marvels: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Daw of Modern Medicine.”

Others get just a little creeped out. Some are shocked.

But however you react to the Mütter Museum, those at its helm want you to know it’s totally OK. In fact, they welcome you to engage with the Mütter in any way you’d like.

But in return they want you to ask yourself: Why is it that you’re feeling the way you do?

Paranormal PA sat down with museum leads and science historians Sara Ray and Erin McLeary, along with President and CEO Dr. Larry Kaiser and Senior Director of Communications Kareen Preble, to discuss the Mütter Museum’s path forward after public backlash, employee exits and leadership changes.

So, in honor of Mütter offering his famed collections on Dec. 11, 1858, read on, to learn more about this unique and wonderful place. (Please note that this interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Visitors examine a display of skulls from the Josef Hyrtl Collection at the Mütter in August. The collection of 139 human skulls was created by Hyrtl to disprove the claims of phrenologists who believed cranial features indicated intelligence and personality. (Photo by Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty Images, file)Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty Images

Visitors examine a display of skulls from the Josef Hyrtl Collection at the Mütter in August. The collection of 139 human skulls was created by Hyrtl to disprove the claims of phrenologists who believed cranial features indicated intelligence and personality. (Photo by Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty Images, file)Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty Images

Right off the bat, the museum has had a little bit of a tumultuous past few years, with the removal of those online exhibits and videos for ethical review, due to the criticism that the display of such remains was insensitive. What would you say to those people now that there’s a revamp of where the museum is going?

Sara Ray: I think one of the things we’re trying to do is, you know, invite people to see that there’s been a lot of conversation about change at the museum. But when you come to visit, there’s very little that’s been changed.

For instance, I started my journey here as a volunteer docent back in 2014, giving tours. And when I came back in January, one of the first things I did in this role was to shadow a docent, and I was, like, “This is the the same tour.”

[For example], Chang and Eng Bunker, who are the most well-known specimens on display, or the most well-known conjoined twin specimens, they have not gone anywhere. The fetal skeletons that are conjoined at the head, which is a very common emblem of the museum, those are still on display.

Most things are still there, but also, just as a regular practice of museum stewardship, you swap exhibits in and out. Erin can speak to this in a very, very detailed way, but we’ve got so much more in the collection that we do on display. And so if you go around and you talk to any museum about the regularity with which they switch out specimens, this is a regular part of the practice.

What would you say to people, then, who still view the museum — and the display of human remains — as insensitive or macabre?

SR: What I’d ask people to do is think about museums as a conversation between the visitor and the past: If you’re arriving to an exhibit where you see fetuses with congenital abnormalities, and if you have that reaction, if you say, “This seems macabre, this seems inappropriate, I don’t like this.” What we want you to do is say, “Why not? What’s the thing that you’re responding to?”

And what I found is that people answer that question in really different ways. Sometimes it’s just, “This is surprising. I’ve never seen this before, and that ‘macabre’ warning flag in my mind is that it’s just surprising, and I don’t really know what to do with it.” The museum should meet you where we you are on that and tell you, “OK, yeah, it is surprising.”

Sometimes people’s response that you’re describing is because, you know, these bodies look so profoundly different than what they expect. They worry that there was pain or there was suffering, that there was some bodily experience that feels really difficult to grapple with.

OK, we can meet you where you are on that, and talk about disability, and what that means to live in a body that sort of defies or may goes outside of the expected boundaries of what a body looks like.

Sometimes people come to us and say, “Oh my God, this little fetus specimen, it looks so macabre, it’s inappropriate to have these on display.” And when you ask them why, what they talk about is an experience with pregnancy loss, or someone that had experienced pregnancy loss, which is really difficult to talk about, where there’s not really a lot of forums for people to talk about publicly.

So people who are having that reaction to our exhibits, I absolutely welcome that. What I would ask them in return is to push it a little bit further and ask, “What’s the response?”

Sara Ray, senior director of interpretation and engagement at the Mutter Museum Historical Medical Library, examines wax models of the faces of patients who suffered from leprosy. (Photo by Matthew Hatcher/afp/AFP via Getty Images, file)Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty Images

Sara Ray, senior director of interpretation and engagement at the Mutter Museum Historical Medical Library, examines wax models of the faces of patients who suffered from leprosy. (Photo by Matthew Hatcher/afp/AFP via Getty Images, file)Matthew Hatcher/AFP via Getty Images

That’s fascinating, because it hits the nail on the head — people are so OK with looking at mummies, for example, which are corpses as well. But when it’s these medical abnormalities, so to speak, some people seem to clutch their pearls. Is there a piece in the museum that you’ve seen elicit this reaction the strongest?

SR: The [teratological] exhibit is the one that brought that up the most for people. And it brought up such a very, you know, the sort of things I said before, right? Sometimes it’s pregnancy loss, sometimes it’s a disability, sometimes it’s about reproductive rights access.

One of the other displays I thinks comes up a lot is with Chang and Eng Bunker, who — and these aren’t biological specimens; this is a death cast — until, maybe, 15 years ago were the oldest surviving conjoined twins in history.

And the megacolon, which we know comes from a man called Joseph Williams. People’s immediate response is the sort of potty humor of it; it’s really hard to resist that reaction of, “Oh, my God, [what] a huge amount of solid waste!”

And what I’ve always found is all you have to say to people is, “Yeah, that’s a huge amount of solid waste — can you imagine that being in your body all the time?” And people within a blink of an eye go, “Oh my God, yeah. That must have been really uncomfortable. That must have been really debilitating.”

It’s not that hard to kind of go from this is a specimen, and telling you the facts about the specimen itself in a way that invites this very light reaction to imagine …the lived experience of disability and what it means to live in a body that limits the choices that you can make.

So Erin and I talk a lot about the ability of history — and honest analytical history — to open up an expanded sense of empathy for how you navigate the world around you today.

What purposes do you think the museum serves in modern times? What do you think people get from it, apart from the shared empathy you referred to and humanization of these stories that these exhibits tell?

Erin McLeary: I think we recognize that we have a unique collection that can provoke unique forms of curiosity and raise unique questions among our visitors. And I think we have with that an opportunity to, again, lean into historical thinking, building the skills of being able to imagine different lives, different bodies, different lied experiences and not only that from a bodily perspective, but the history of medicine.

I think it is an incredible tool for helping people think about the way in which knowledge and expertise works. The ways in which we’re not on a march of progress from barbarism to where we are today or where we’ll be in the future. What we’re actually experiencing is a very shared experience with people in the past, right? We are making our health care, our medical care, about what we think about expertise.

Using a framework that we have been taught, that we are swimming in, feels very natural to us. We need to remember that people in the past were also making excellent choices within the framework and the knowledge system in which they were immerse.

And I think the history of medicine really enables us to both approach the shared understanding of living in a body, but also this shared history of leading to negotiate systems of expertise and power and ideas about what gives health and what subtracts from it.

It seems like, for a lot of people, the museum is a haven and a safe place. A lot are even clamoring to donate themselves. What do you make of that?

SR: I understand why people have that impulse … the life that you live is never separate from the body that you live in it. And so I think what happens is that people to us for any number of reasons, and it is so natural that you connect very, personally with what you see, because these are also people that had a body.

“[Some] people then take it to the next step and say, “I want to donate to the museum.” [The museum now only considers remains that are offered by a living, primary donor or by a decedent via bequest.]

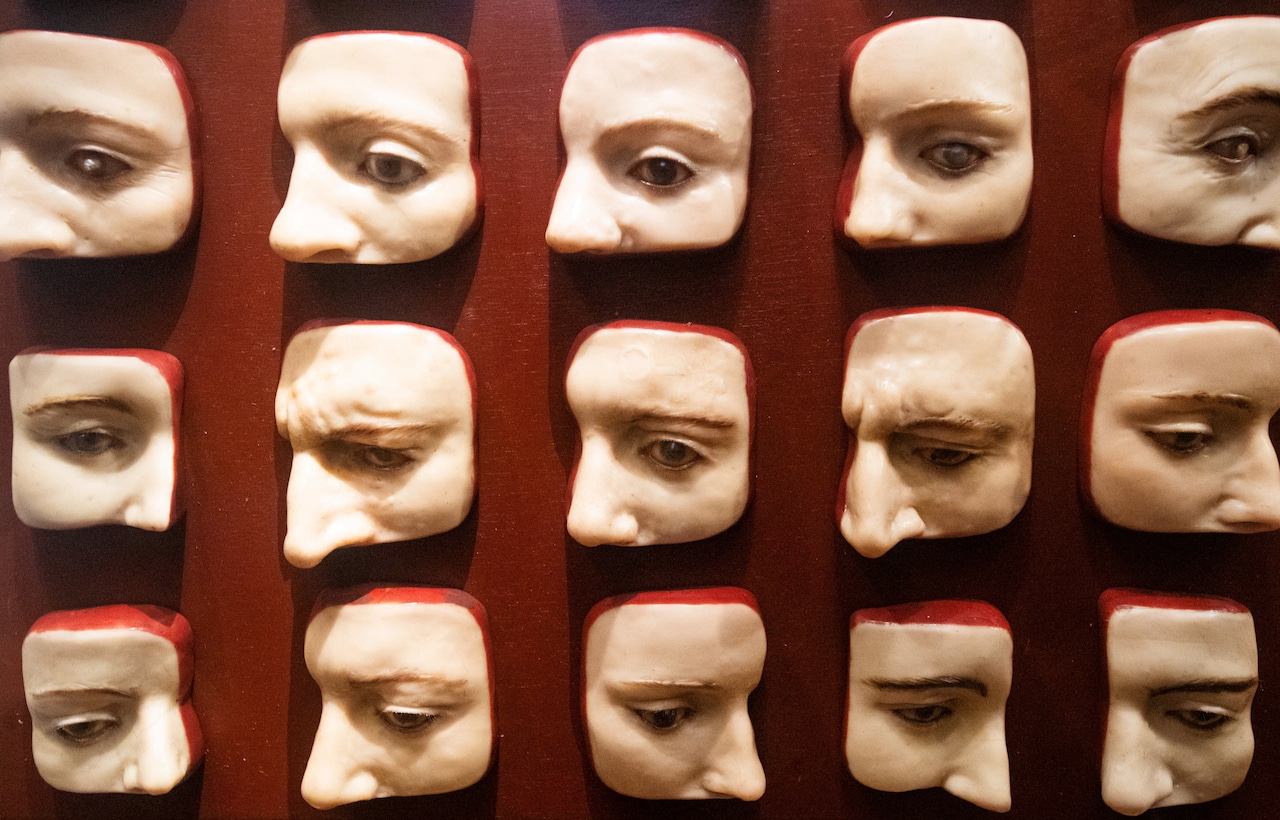

Wax moldings of various eye diseases hang at the Mütter Museum Historical Medical Library. (Photo by Matthew Hatcher/afp/AFP via Getty Images, file)afp/AFP via Getty Images

Wax moldings of various eye diseases hang at the Mütter Museum Historical Medical Library. (Photo by Matthew Hatcher/afp/AFP via Getty Images, file)afp/AFP via Getty Images

What’s the vetting process like?

EM: There’s a very standard vetting process for museums, regardless of what type of material it is. So you typically do not materials that are duplicative; if you already have it, you don’t take another example. And this is for any type of material. If you were unable to care for it, too, you would decline it.

There are certain variant museum-esque things that get considered. Like if there is a clear ownership history of this material; if there is not, we would not take it. And again, that could be a book, a painting, a human brain. These are just principles of the museum field.

And then, finally, does the material have research or exhibition value? If we can’t use it, if it’s not of interest and value to scholars or of interest or value to the public, then you would decline. That’s another, museum, industry-wide principle. Part of being a responsible steward of the materials in your collection is really understanding how your institution will activate that material for the benefit of the public.

Now, you don’t have to answer this if you don’t want to: Would you ever consider donating yourselves to the Mütter Museum?

SR: I have very specific ideas about what I want done with my body after death, and it does not involve being in a museum. Not because I don’t think that it’s not a valuable place to be; it’s just not where I want to be.

Or to go back to Erin’s response, doing this work has made me think a lot about what is the use of my body after death? And for me, that answer is not being in a museum.

EM: Mine is very similar to Sara’s in that I would not see the affirmative use in my rather ordinary body. And within the familial and social context i which I exist, that would not be the affirmative use that would I think would be the [best] for me. But that’s a me answer.

SR: We just decided to give our lives to the museum.

Editor’s note: Welcome to the world of “Paranormal PA,” a PennLive series that delves into Pennsylvania-grown stories of spirits; cryptids; oddities and legends; and the unexplained. Sign up here to get our Paranormal PA newsletter delivered to your inbox.