Rekia Boyd would have been 36 years old last month. To honor that milestone, A Long Walk Home — the art organization that empowers young people to end violence against Black girls and women — held a party for family and community to celebrate her life.

An off-duty Chicago police officer shot and killed Boyd near Douglass Park in 2012. She was 22 years old. The officer was acquitted of criminal charges in the case.

ALWH has been saying her name ever since — honoring her and the Black girlhood that she and others like her embody. ALWH provides artistic, advocacy and leadership programming to Black girls and young women to help them drive change within their communities. Boyd was one of several Black girls and women featured in ALWH’s “Black Girlhood Altar,” a community monument to missing and murdered Black girls.

The November celebration at Homan Square’s Nichols Tower was ebullient with food, camaraderie and conversation about Boyd’s legacy. Many attendees wore Boyd’s favorite color, yellow, and commiserated amidst pictures of a young, smiling Boyd and renderings of projects artists hope will be developed to pay homage to Boyd in North Lawndale’s Douglass Park. Artists Nina Cooke John, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, Tiff Massey, Sonja Henderson and Nekisha Durrett gave presentations. The proposals are finalists for the Rekia Boyd Monument Project.

“Rekia was something different,” said Boyd’s sister, Natasha Williams. “We used to call her the $5 sister, because she’d ask for $5 and take our children — have them for 10 hours a day. She just needed $5 for nine children to take out to the park. I don’t know what they did, but they were happy. Rekia was all about smiles. She had this crazy laugh. That’s how a lot of people know her and her saying, ‘Hey girl!’”

Cooke John’s vision for the Rekia Boyd Monument Project is called “Sweet Harbor.” It centers various wood shapes in a lush green space for sitting, playing and engaging with.

A rendering of the proposed installation, “Sweet Harbor.” (Nina Cooke John)

A rendering of the proposed installation, “Sweet Harbor.” (Nina Cooke John)

“I see 10-year-olds walking on it like you might a balance beam or jumping off and over it,” said Cooke John about her public art proposal. “I see a lot of temporary activation as well. The idea that you can bring with you your ropes, tie them and use them for double dutch. It (the wood) becomes the instigator for new creativity, but it still has parts of it that stay the same. It can be dynamic in terms of how you engage with it. … It changes with the seasons.”

Cooke John is interested in collecting words from healing circles and capturing sounds of people having a good time to create a score that plays. The soundscape is an audio component that makes the park space multi-sensory.

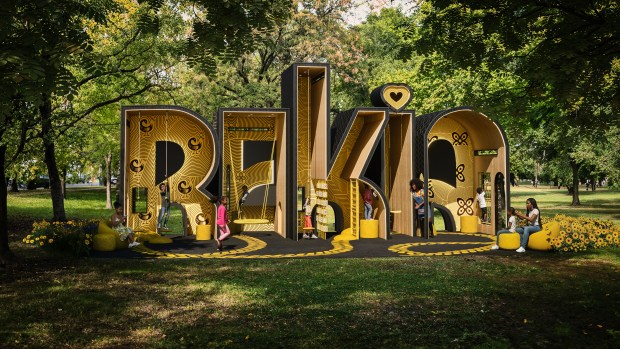

Massey’s endeavor, “Rekia’s Sound Garden,” features sunflowers; Durrett’s work “R.E.K.I.A,” makes each letter of her name a playground where children can play; Fazlalizadeh’s project “For Rekia, For Us” is ladened with flowers; and Boyd’s visage incorporated in a plaza with powerful words about Black girls; while Henderson’s monument concept includes a sonic garden tuned by Sadie Woods with a 9-foot bronze statue of Boyd in the parabola garden. Boyd’s bodice is draped in a gown covered in bronze bells that can be rung and engraved by community members. The space is multi-generational and centers play and rest. Henderson said it’s about frequency, and coming together in fellowship. If her proposal is chosen, she will also have a film component, one about the making of the monument and retelling Boyd’s story.

A rendering for the Rekia Boyd Monument Project. (Sonja Henderson)

A rendering for the Rekia Boyd Monument Project. (Sonja Henderson)

“Rekia Boyd, who we revere and love, was a human being, and it’s important to acknowledge her as such,” Henderson said in her presentation. “She was taken from us because she was being too loud. And so our vision is to give her her voice back. We’re doing that with a bell. This is the voice that is going to be heard around the world. Your voices now perpetuate Rekia’s story and her promise. You are the future. You are her future.”

Each proposal showcased ALWH’s decades-long mission of empowerment.

“This is a rare thing — there aren’t that many Black women monuments,” said Scheherazade Tillet, ALWH’s co-founder and executive director. “Not only is it about Rekia … we don’t have these sculptures to represent us. It’s even more sacred as a reclaiming of space. I was told to look for a yellow banner around a tree in 2015 to remember Rekia. That was the only marker that you had. I think there is something joyful in this moment. It’s a heavy topic, but that’s the work of a long walk home — every project we do, we keep on remembering her, and we bring on other people.”

A rendering of the proposed installation, “R.E.K.I.A.” (Nekisha Durrett)

A rendering of the proposed installation, “R.E.K.I.A.” (Nekisha Durrett)

ALWH is helming the Rekia Boyd Monument Project in partnership with the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, Chicago Parks District and Monument Lab (part of the Chicago Monuments Project). The monument is among eight new monuments funded through a partnership between DCASE and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. A decision on the selection for the monument is slated for January 2026, with fruition expected in 2026-27, according to Lydia Ross, DCASE senior strategist, who has been leading the Chicago Monument Project recently. The project started in 2020 as a response to the city of Chicago’s need for a larger reckoning with monuments and more inclusive narratives of the city’s history.

“These projects are deeply emotional, personal, also political,” Ross said. “When people have been suppressed, ignored, misrepresented for centuries… to have an opportunity where we’re saying, ‘how do we change the built environment of our city?’ That passion isn’t going away.”

A rendering of the proposed installation, “Rekia’s Sound Garden.” (Tiff Massey)

A rendering of the proposed installation, “Rekia’s Sound Garden.” (Tiff Massey)

Just like the love and memories of Boyd.

“I know she loved children. She always loved children. She liked the color yellow, and she was very outgoing, adventurous,” Williams said. “To see that someone is taking time out to keep Rekia’s name alive… I really appreciate what everyone is doing for our family.”